Category: East Asia

Two arrested on charges relating to Chinese police station in New York

Two individuals were arrested in New York on Monday on federal charges that they operated a police station in lower Manhattan for the Chinese government, prosecutors said. “Harry” Lu Jianwang, 61, of the Bronx, and Chen Jinping, 59, of Manhattan, both U.S. citizens, worked together to create an overseas branch of the Chinese government’s Ministry of Public Security (MPS), federal officials said. They opened the station in an office building in Chinatown, a neighborhood in Manhattan. The station was closed last year, according to the prosecutors. Federal officials also filed complaints against more than three dozen officers with the MPS, accusing them of harassing Chinese nationals living in New York and other parts of the United States. The officers, who remain at large in China, targeted individuals in the United States who expressed views contrary to the position of the Chinese government, according to the federal officials. The Chinese Embassy in Washington has not replied to queries about the announcement regarding the arrests of Lu Jianwang and Chen Jinping. It isn’t clear if the two have lawyers. A Justice Department official said that the police station was part of an effort by the Chinese government to spy on and frighten individuals who live in the United States. “The PRC, through its repressive security apparatus, established a secret physical presence in New York City to monitor and intimidate dissidents and those critical of its government,” said Matthew G. Olsen, an assistant attorney general with the Justice Department’s National Security Division, referring to the acronym for the People’s Republic of China. A six story glass facade building, second from left, is believed to have been the site of a foreign police outpost for China in New York’s Chinatown, Monday, April 17, 2023. Credit: Associated Press Lu Jianwang and Chen Jinping were charged with conspiring to act as agents of the Chinese government and of obstructing justice through the destruction of evidence of their communications with a Chinese ministry official, according to a complaint filed in a federal court in Brooklyn. They allegedly destroyed emails that they had exchanged with an official at the MPS, according to federal officials. Lu had been responsible for assisting the Chinese security ministry in various ways, according to the federal officials. They said that Lu had helped apply pressure on an individual to return to China and assisted in efforts to track down a “pro-democracy activist” also living in the United States. The existence of a police station in Chinatown came to light last year. According to federal officials, Chinese security officials ran the outpost, as well as dozens of other stations in cities and towns around the world. The FBI’s arrest of individuals in connection to the Chinatown police station is the latest effort by U.S. officials to curtail what they describe as the Chinese government’s activities in the United States. The arrest of the two individuals in New York is also a reminder of the tense relationship between the two countries. Lately, U.S. officials have highlighted the Chinese government’s influence operations and attempts to sway people’s opinions so that they view Chinese government policies in a more favorable light. “We’ve been hearing a lot about China’s influence campaigns – the idea that China is on the move in the United States,” said Robert Daly, the director of the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States at the Wilson Center in Washington. “But this potentially puts Chinese agents right in downtown Manhattan.”

EU lodges protest over China’s detention of rights lawyer and activist wife

The European Union has lodged a protest with China after police detained veteran rights lawyer Yu Wensheng and his activist wife Xu Yan ahead of a meeting with its diplomats during a scheduled EU-China human rights dialogue on April 13. “We have already been taken away,” Yu tweeted shortly before falling silent on April 13, while the EU delegation to China tweeted on April 14: “@yuwensheng9 and @xuyan709 detained by CN authorities on their way to EU Delegation.” “We demand their immediate, unconditional release. We have lodged a protest with MFA against this unacceptable treatment,” the tweet from the EU’s embassy in China said, referring to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell had been scheduled to travel to China from April 13-15 for the annual EU-China strategic dialogue with Foreign Minister Qin Gang, and to meet with China’s foreign policy chief Wang Yi, as well as the new Defense Minister Li Shangfu. The visit, during which Yu and Xu had an invitation to go to the German Embassy for the afternoon of April 13, was to have followed last week’s trip by European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen and French President Emmanuel Macron. But Borrell postponed the visit after testing positive for COVID-19, according to his Twitter account. Chinese human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang, who is also said to have been detained recently, is seen on a laptop screen in Beijing as he speaks via video link from his home in Jinan, in China’s eastern Shandong province, April 23, 2020. Credit: AFP The EU Delegation said rights attorneys Wang Quanzhang, Wang Yu and Bao Longjun have also been placed under house arrest, but gave no further details. Police officers read out a notice of detention to Xu and Yu’s 18-year-old son on Saturday night, giving the formal date of criminal detention as April 14, but didn’t leave any documentation with him or allow him to take photos of the notice, Wang Yu told Radio Free Asia on Monday. Catch-all charge Citing fellow rights attorneys Song Yusheng and Peng Jian, who visited the family home on Sunday, Wang said: “[The son] said that his parents were detained on the charge of picking quarrels and stirring up trouble” – a catch-all charge used to target critics of the Communist Party. “The police showed his son the notice of criminal detention, but he was not allowed to take pictures, and they didn’t leave the notice for him. He was only shown it,” Wang Yu said. “They carried out a search of their home.” Around seven officers searched the family home and took away a number of personal belongings without showing a warrant or issuing receipts, according to the rights website Weiquanwang. Wang Yu, who received a call from the couple’s son on April 16, said the young man is now also under surveillance. “The authorities sent people to stand guard over Yu Wensheng’s son, both inside and outside their home,” Wang said. Defense lawyers blocked She said police had prevented lawyers Song and Peng from representing the couple as defense attorneys. “Song Yusheng and Peng Jian went to Yu Wensheng’s house and took his son to dinner,” she said. “They wanted his son to sign a letter instructing them as attorneys, but Peng Jian told me that the police refused to sign off on it.” “Yu Wensheng’s brother told me that the police told him that Xu Yan has already hired a lawyer,” she said. “This is the same as the way they handled the July 2015 crackdown, preventing family members from instructing lawyers, and stopping the lawyers from defending [detainees].” Since a nationwide crackdown on hundreds of rights attorneys and law firms in 2015, police have begun to put pressure on the families of those detained for political dissent to fire their lawyers and allow the government to appoint a lawyer on their behalf, in the hope of a more lenient sentence. Wang Yu said the charges against the couple were trumped up. “Criminal detention is legally equivalent to being suspected of a crime,” she said. “But according to the information we have from family members and online, there is no evidence that Yu Wensheng or Xu Yan engaged in any illegal activities.” Wang Qiaoling, wife of rights lawyer Li Heping, said her family is currently also under surveillance. “When we were taking our kids to class on Sunday morning, we saw that there were cars following us, and they followed us onto the expressway,” she said Monday. “It was the same today.” “They always place us under surveillance whenever a foreign leader visits China, but we don’t understand why they are doing it now, when the [scheduled] visit is over,” she said. The Spain-based rights group Safeguard Defenders said the couple’s disappearance should be a matter for EU-China relations, noting the use of “residential surveillance” to prevent fellow rights lawyers from defending the couple. “[Residential surveillance] is growing in use and new legal teeth have made it a far harsher experience,” the group said via its Twitter account. Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

G7 talks tough on Ukraine, Taiwan and Korea during Blinken’s Asia trip

UPDATED AT 07:34 a.m. ET on 2023-04-17. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken is in Japan where he, together with other foreign ministers from the Group of Seven (G7) nations, discussed a common approach to the war in Ukraine Monday, confirming “that they remain committed to intensifying, fully coordinating and enforcing sanctions against Russia, as well as to continuing strong support for Ukraine,” according to a Japanese Foreign Affairs Ministry statement. The statement was in line with the goals of the Biden administration, which are to shore up support for Ukraine and to ensure the continued provision of military assistance to Kyiv, as well as to ramp up punishment against Russia through economic and financial sanctions, a senior official from Blinken’s delegation told the Associated Press ahead of the meeting. Earlier G7 ministers vowed to take a tougher stance on China’s threats to Taiwan, and North Korea’s missile tests. Meanwhile, Britain’s Financial Times reported that China was refusing to let Blinken visit Beijing over concerns that the FBI will release the results of an investigation into the suspected Chinese spy balloon downed in February. The FT quoted four people familiar with the matter as saying that “China had told the U.S. it was not prepared to reschedule a trip that Blinken cancelled in February while it remains unclear what the administration of President Joe Biden will do with the report.” It is unclear when the trip would be rescheduled. The U.S. military shot the Chinese balloon down over concerns that it was spying on U.S. military installations but China insisted that it was a weather balloon blown off course due to “force majeure.” The incident led to Blinken abruptly canceling his ties-mending trip to Beijing, during which he was expected to call on Chinese leader Xi Jinping. The relationship between Washington and Beijing has been strained in the last few years over issues such as China’s threats to Taiwan and security concerns in the Indo-Pacific. Upgrading U.S.-Vietnam partnership Antony Blinken arrived at Karuizawa in Nagano prefecture in central Japan on Sunday after a visit to Vietnam to promote strategic ties with the communist country. This was Blinken’s first visit to Hanoi as U.S. Secretary of State. The U.S. is building a U.S.$1.2 billion compound in Hanoi, one of its largest and most expensive embassies in the world. During his visit, Blinken met with Vietnam’s most senior officials, including the General Secretary of the Communist Party, Nguyen Phu Trong, to discuss “the great possibilities that lie ahead in the U.S.-Vietnam partnership,” the secretary of state wrote on Twitter. Secretary of State Antony Blinken (L) meets with Vietnam’s Communist Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong at the Communist Party of Vietnam Headquarters in Hanoi, Vietnam, April 15, 2023. Credit: Andrew Harnik/Pool via Reuters Two weeks before Blinken’s visit, Trong and his U.S. counterpart Joe Biden had a phone conversation during which the two leaders agreed to “promote and deepen bilateral ties,” according to Vietnamese media. Former enemies Hanoi and Washington normalized their diplomatic relationship in 1995 and in 2013 established a so-called Comprehensive Partnership to promote cooperation in all sectors including the economy, culture exchange and security. Vietnam’s foreign relations are benchmarked by three levels of partnerships: Comprehensive, Strategic and Comprehensive Strategic. Only four countries in the world belong to the top tier of Comprehensive Strategic Partners: China, Russia, India and South Korea. Vietnam has Strategic Partnerships with 16 nations including some U.S. allies such as Japan, Singapore and Australia. U.S. officials have been hinting at upgrading the ties to the next level Strategic Partnership which offers deeper cooperation, especially in security and defense, amid new geopolitical challenges posed by an increasingly assertive China. Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh told the U.S. Secretary of State on Saturday in Hanoi that the consensus reached amongst the Vietnamese leadership is to “further elevate the bilateral partnership to a new height” adding that “relevant government agencies have been tasked with looking into the process.” Vietnam analysts such as Carl Thayer from the University of New South Wales in Australia said that an upgrade of Vietnam-U.S. relationship to Strategic Partnership within this year is possible, despite concerns that it would antagonize Beijing. The U.S. is currently the largest export market and the second-largest commercial partner for Vietnam. Hanoi aims to benefit across the board from U.S. assistance, especially in trade, science and technology, Thayer told Radio Free Asia. Vietnam as one of the South China Sea claimants has been embroiled in territorial disputes with China and could benefit from greater cooperation in maritime security. In exchange, “the U.S. would benefit indirectly by assisting Vietnam in capacity-building to address maritime security issues in the South China Sea to strengthen a free and open Indo-Pacific,” said Thayer. “The U.S. is trying to mobilize and sustain an international coalition to oppose Russia’s war in Ukraine and to deter China from using force against Taiwan and intimidation of South China Sea littoral states,” the Canberra-based political analyst said. Hanoi’s priority Some other analysts, such as Bill Hayton from the British think tank Chatham House, said that there might have been a miscalculation on the U.S.’s part. “Washington is now taking itself for a massive ride in its misunderstanding of what Vietnam wants from the bilateral relationship,” Hayton said. “All the Communist Party of Vietnam wants is regime security. It has no interest in confronting China,” the author of “A brief history of Vietnam” said. Blogger Nguyen Lan Thang was sentenced to six years in prison for ‘spreading anti-state propaganda’ on April 12, 2023. Credit: Facebook: Nguyen Lan Thang Just before Blinken landed in Hanoi, a dissident blogger was sentenced to six years in prison for “spreading anti-state propaganda.” Nguyen Lan Thang was also a contributor to Radio Free Asia. The U.S. State Department condemned the sentence and urged the Vietnamese government to “immediately release and drop all charges against Nguyen Lan Thang and other individuals who remain in detention for peacefully exercising and promoting human rights.” “Vietnam is an…

Bear more children – they’re like consumer durables, Chinese economist urges

Have more children – it’s your patriotic duty. They are like durable consumer goods that you pay off over the long haul, but bring far more benefits. That was the message from a prominent Chinese economist at a government-backed think tank, and the most recent effort by the Communist Party’s campaign to boost the country’s flagging birth rate that includes a slew of economic perks for couples – long limited to just one child – to have more children. “Durable consumer goods pay off in the long run, so it’s wrong for young people not to have children – their value exceeds that of the other goods you buy,” said Chen Wenling, chief economist at the China Center for International Economic Exchanges. Chen’s comments sparked an online outcry. Some said that people in China are all regarded as “consumables,” rather than human beings. Others said those who decide not to have children are smart. “Today’s society has driven young people to the point of desperation,” commented one social media user. “I want a place to live, but I can’t afford one. I don’t have time for fun, and I can’t afford to raise a child – this comment from this expert is so arrogant!” Others were more cynical. “People may be consumer goods in other countries, but here, we’re either inferior, hostages or ***holes,” commented @psychotic_relapse from Shandong on Weibo. “It’s poor thinking to treat children as private property,” wrote @Gusu_Bridge from Jiangsu, while @Guangzhou_old_dog said those in power should quit making “tedious and arrogant” comments. “They should come up with some policies and test them out to see if they work in practice,” the user wrote. “Back in the 1950s, they wanted people to have more kids, then it was family planning in the 1980s, and now we’re back to encouraging people to have more kids again,” wrote @My_heart_is_still_4325 from Shandong. “But the reality is that it’s not easy to secure housing, medical care, employment or education,” the user wrote, while @plants_vs_zombies_fan wrote: “Having a child in China is the worst investment.” Can’t find jobs Chen’s comments come at a time when youth unemployment is running at around 20% in China, with around 10 million graduates about to enter the labor market to compete with those who are already unemployed. A current affairs commentator who gave only the surname Chen agreed. “Most people don’t have the money to find a partner right now, because all of that requires money for food, transportation and going out,” Chen said. “Most young people are demotivated by that.” Job seekers visit a booth at a job fair in Beijing, Feb. 16, 2023. Credit: Reuters “It’s not that they don’t want a partner; the economic pressures are just too huge, and far worse than before,” he said. Li Jiabao, who moved from mainland China to live in democratic Taiwan, said there is a huge amount of disillusionment with government policy from the same age group that Beijing is counting on to raise more children. “After three years of violent enforcement of the zero-COVID policy in China, young people see this government as extremely bureaucratic and careless of human life,” Li said. “I think this is the main reason why young people are so disgusted with this expert.” One-child policy In 2016, China abandoned its 35-year “one-child policy,” which penalized parents with more than one child, amid concerns about its birth rate, raising the limit to two. In 2021, that was further loosened to three – and now there are no limits on the number of children a couple can have. Authorities have recognized they need to offer incentives to couples to have more children amid the economic pressures of modern China. “After three years of violent enforcement of the zero-COVID policy in China, young people see this government as extremely bureaucratic and careless of human life,” says Li Jiabao, a mainland Chinese dissident who moved to Taiwan. Credit: RFA A plan announced in August 2022 offers “support policies in finance, tax, housing, employment, education and other fields to create a fertility-friendly society and encourage families to have more children,” promising community nursery services, better infant and child care services at local level, flexible working and family-friendly workplaces, and safeguarding the labor and employment rights of parents. But rights activists said discrimination in the workplace still presents major obstacles to equality for Chinese women, despite protections enshrined in the country’s law. Chinese women still face major barriers to finding work in the graduate labor market and fear getting pregnant if they have a job, out of concern their employer will fire them. And young people in China are increasingly ruling marriage out of their plans for the future, with marriage registrations falling for several years in a row. Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

Blinken’s trip to Vietnam may result in possible upgrade for US-Vietnam ties

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken is hoping to upgrade relations with Vietnam to a strategic partnership from the current comprehensive one during meetings with officials in Hanoi on Friday and Saturday, amid China’s rising regional power and aggression in the South China Sea. Blinken is scheduled to meet with senior Vietnamese officials to discuss “our shared vision of a connected, prosperous, peaceful, and resilient Indo-Pacific region,” the State Department said in an April 10 statement. Blinken also will break ground on a new U.S. embassy compound in Hanoi. Blinken’s trip comes about two weeks after a phone call between U.S. President Joe Biden and Nguyen Phu Trong, general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam. July will mark the 10th anniversary of the 2013 U.S.-Vietnam Comprehensive Partnership. Vietnam already has “strategic” partnerships with many U.S. allies, but the U.S. itself has remained at the lower “comprehensive” partnership level despite improvements in the bilateral relationship because disaccord over human rights hindered talks. But political analysts believe Vietnam may agree to boost the relationship this time around. Ha Hoang Hop, an associate senior fellow specializing in regional strategic studies at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, a research center in Singapore, said he was certain that Vietnam would upgrade its partnership with the U.S. during Blinken’s visit. “A good and better relationship between Vietnam and the U.S. will certainly contribute to maintaining the stability and security of Southeast Asia, as well as of a broader region,” he told RFA. “It will also significantly make Vietnam more proactive, confident, and stronger in ensuring its stability and security given many complexities in the world and in the region.” Vietnam has comprehensive partnerships with a dozen other countries, strategic partnerships with another 13, and comprehensive strategic partnerships with China, Russia, India and South Korea. A boost in relations between the U.S. and Vietnam would prompt China to react across the board in terms of security, economic development, trade and cultural exchange, Hop said. “Even now, we all see that China does not want Vietnam to have good relations with other countries,” he said because Beijing believes it would not bode well for its claims in the South China Sea over which it has sparred with Hanoi for decades. “We all know they have used so-called ‘gray zone tactics’ to disturb, annoy and cause instability,” Hop said. “Then, they gradually encroach and at some point when other countries, including Vietnam, let it go, they will achieve their sovereignty goals.” Making Hanoi happy Prominent human rights lawyer Le Cong Dinh also waxed positive on the possible upgrading of bilateral ties between the U.S. and Vietnam. “This relationship is considered in the context of the U.S.’s strategy in the Indo-Pacific region,” he said. The strategy, issued by the Biden administration in early 2022, outlines the president’s vision for the U.S. to more firmly anchor itself in the Indo-Pacific region in coordination with allies and partners to ensure the region is free and open, connected, prosperous, secure and resilient. “Vietnam’s position and role is quite important to the U.S.’s regional strategy, especially in terms of containing China in the South China Sea,” said Dinh, a former vice-president of the Ho Chi Minh Bar Association. “Therefore, the U.S. always tries to find ways to make Hanoi happy and deepen the bilateral relationship.” He went on to suggest that for the U.S. regional security issues have taken precedence over human rights in Vietnam. But Dinh cautioned that to avoid upsetting China, the Vietnamese government must take a tactful and smart approach to upgrade bilateral ties with the U.S. and not hastily use the term ‘strategic partnership.’” “Doing so, in reality, the two sides can work on the issues that a strategic partnership allows us to do, which a comprehensive partnership does not. China’s state-run Global Times newspaper on April 9 cited Chinese experts who said Blinken’s visit may yield results in maritime security or improvement in economic cooperation, but it would not affect Vietnam’s overall strategy because there are still inherent and structural contradictions – ideological and historical issues – between Vietnam and the U.S. Translated by Anna Vu for RFA Vietnamese. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Matt Reed.

North Korea warns parents to send their truant kids to school

It’s been more than 10 days since the new school year began in North Korea, and a large number of poor children have yet to show up for classes because they are needed for farm work during the planting season. So authorities are warning their parents to send them to school or face interrogation or public shaming, sources in the country told Radio Free Asia. Most North Korean elementary schools should have around 30 students in each classroom, but one or two from each class have yet to show up for their first day of school, a resident in the northern province of Ryanggang, who is knowledgeable about the education sector in Paegam county, told RFA’s Korean Service Monday on condition of anonymity for security reasons. “Today, the county’s education department sent a notice to parents who have not sent their children to school … warning that they will notify the party committees and their parents’ workplaces if they don’t attend,” he said. The warnings come after previous efforts to get the children to school failed, according to the source. “When the class attendance rates are down, the homeroom teacher will be interrogated,” he said. “Even if their classmates come to their homes to pick them up, or if the teacher visits with the parents, there are still quite a few children who do not come to school.” The source said that the children who aren’t attending school are from families experiencing economic hardship. “The reason why children do not come to school is because they have to help their parents, who are busy preparing their small plots of land for farming in the mountains as the planting season begins,” he said. Matter of survival Planting season is vital for many rural families to survive. “Farming on their private plots is the most important activity for the year because corn, beans, potatoes and whatever else can be grown on small plots of land will be the only food these households … have to stay alive this year,” the source said. A North Korean boy works on a collective farm in South Hwanghae province. Credit: Reuters file photo The same problem existed in previous years, but it fell to the teachers to ask the parents to send their kids to school, he said. This is the first year that parents are getting an official warning, and it appears to be highly unusual. While there’s no accompanying punishment laid out in the warning other than being reported to the party committee, the potential for public disgrace by such a high-ranking institution makes the report alone a serious threat, he said. For the country’s poorest, going into the mountains to find some empty land to grow vegetables is a matter of survival. North Korea has suffered from chronic food shortages for decades, and a suspension of trade with China during the COVID-19 pandemic made the shortages worse. At one point during the pandemic, the government told the people that they would no longer receive rations and would be on their own for food. The impoverished children work to cultivate the newly slashed and burned land, so they have no time to go to school. Summoned for questioning In the city of Kimchaek, in the northeastern province of North Hamgyong, the problem is so dire that authorities there began calling in the parents for interrogation, a source there told RFA on condition of anonymity to speak freely. “There are a total of 28 students in my kid’s class in elementary school, but four of them are not attending,” she said. “Last week, schools in the city submitted absentee lists to the education department, and included their parents’ jobs, their titles and home addresses.” The source said she believes that the interrogations began on Monday. “Interrogating the parents will not guarantee a 100% attendance rate,” she said. “For families who do not have food to eat right now or who are struggling to live, it is more important to not starve than it is to send their children to school.” Translated by Claire Shinyoung Oh Lee. Written in English by Eugene Whong. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

Trafficked teens tell of torture at scam ‘casino’ on Myanmar’s chaotic border

It was a clear day when Kham set out from his home in northwestern Laos for what he thought was a chance to make money in the gilded gambling towns of the Golden Triangle, the border region his country shares with Thailand and Myanmar. On that day – a Friday, as he recalled – the teenager had gotten a Facebook note from a stranger: a young woman asking what he was doing and if he wanted to make some cash. He agreed to meet that afternoon. She picked up Kham, 16, along with a friend, and off they went, their parents none the wiser. “I thought to myself I’d work for a month or two then I’d go home,” Kham later said. (RFA has changed the real names of the victims in this story to protect them from possible reprisals.) But instead of a job, Kham ended up trafficked and held captive in a nondescript building on the Burmese-Thai border, some 200 miles south of the Golden Triangle and 400 miles from his home – isolated from the outside world, tortured and forced into a particular kind of labor: to work as a cyber-scammer. Barbed wire fences are seen outside a shuttered Great Wall Park compound where Cambodian authorities said they had recovered evidence of human trafficking, kidnapping and torture during raids on suspected cybercrime compounds in Sihanoukville, Cambodia, in Sept. 2022. Credit: Reuters In recent years, secret sites like the one where Kham was detained have proliferated throughout the region as the COVID-19 pandemic forced criminal networks to shift their strategies for making money. One popular scheme today involves scammers starting fake romantic online relationships that eventually lead to stealing as-large-as-possible sums of money from targets. The scammers said that if they fail to do so, they are tortured. Teen victims from Luang Namtha province in Laos who were trafficked to a place they called the “Casino Kosai,” in an isolated development near the city of Myawaddy on Myanmar’s eastern border with Thailand, have described their ordeal to RFA. Chillingly, dozens of teenagers and young people from Luang Namtha are still believed to be trapped at the site, along with victims from other parts of Asia. The case is but the tip of the iceberg in the vast networks of human trafficking that claim over 150,000 victims a year in Southeast Asia. Yet it encapsulates how greed and political chaos mix to allow crime to operate unchecked, with teenagers like Kham paying the price. This fake Facebook ad for the Sands International is for a receptionist. It lists job benefits of 31,000 baht salary, free accommodation and two days off per month. Qualifications are passport holder, Thai citizen, 20-35 years old and the ability to work in Cambodia. Credit: RFA screenshot The promise of cash Typically, it starts with the lure of a job. In the case of Lao teenagers RFA spoke to, the bait can be as simple as a message over Facebook or a messaging app. Other scams have involved more elaborate cons, with postings for seemingly legitimate jobs that have ensnared everyone from professionals to laborers to ambitious youths. What they have in common is the promise of high pay in glitzy, if sketchy, casino towns around Southeast Asia – many built with the backing of Chinese criminal syndicates that operate in poorly policed borderlands difficult to reach. Before 2020, “a lot of these places were involved in two things: gambling, where groups of Thais and Chinese were going for a weekend casino holiday, or online betting,” said Phil Robertson, deputy director for Asia at Human Rights Watch. “Then, all of a sudden COVID hits, and these syndicates [that ran the casinos] decided to change their business model. What they came up with was scamming.” A motorbike drives past a closed casino in Sihanoukville, Cambodia, in Feb. 2020. As travel restrictions bit during the pandemic, syndicates that ran the casinos shifted their focus from gambling to scams, says Phil Robertson of Human Rights Watch. Credit: Reuters Today, gambling towns like Sihanoukville, in Cambodia, and the outskirts of Tonpheung, on the Laos side of the Golden Triangle, have become notorious for trapping people looking for work into trafficking. But besides these places, there are also numerous unregulated developments where scamming “casinos” operate with little outside scrutiny, including on the Thai-Burmese border. Keo, 18, had a legitimate job at a casino in Laos when he was contacted via WhatsApp by a man who said he could make much more – 13 million kip ($766) a month, plus bonuses – by working in Thailand. He could leave whenever he wanted, the person claimed. “I thought about the new job offer for two days, then I said yes on the third day because the offer would pay more salary, plus commission and I can go home anytime,” Keo said. He quit his job by lying to his boss, saying he was going to visit his family. A few days later, a black Toyota Vigo pick-up truck fetched him, along with two friends, and they took a boat across the Mekong to Thailand. Scams By that time, Keo realized he was being trafficked – the two men who escorted him and his friends were armed. “While on the boat, one of us … suggested that we return to Laos, but we were afraid to ask,” as the men carried guns and knives. He dared not jump. “Later, one of us suggested we call our parents – but the men said, ‘On the boat, we don’t use the telephone.’ We dared not call our parents because we were afraid of being harmed,” he said. “So, we kept quiet until we reached the Thai side.” Both Keo and Kham told RFA that they were eventually trafficked to Myawaddy Township, an area some 300 miles south of the Golden Triangle. Kham only remembered parts of the journey, when he was made to walk for miles. Keo told RFA Laos he was transported by a…

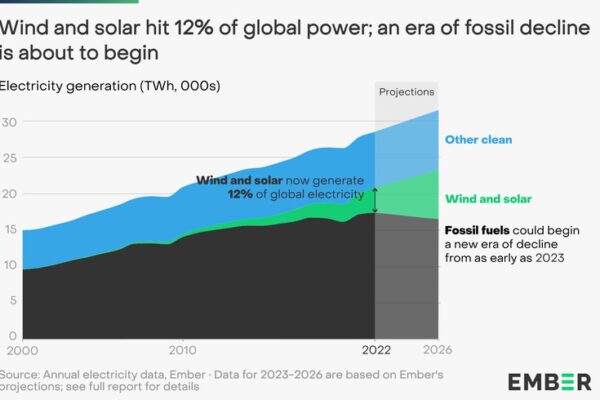

China leads, as wind and solar reach record power generation in 2022

Wind and solar reached a record 12% share of global electricity generation in 2022, up from 10% in 2021, with China leading in both sectors, a report by an independent think tank said Wednesday. Solar was the fastest-growing source of electricity for the eighteenth year in a row, rising by 24% year-on-year, according to the fourth Global Electricity Review released by Ember, a U.K.-based energy and climate research group. The global growth in wind and solar power was primarily driven by rising use in China, which accounted for 37% of the worldwide increase. Solar’s share of global power output last year was 4.5%, or 1,284 terawatt hours, up from 3.7% in 2021. A terawatt hour is equal to 1 trillion watts of power for one hour. Meanwhile, 312 terawatt hours of wind energy were added to global electricity generation in 2022. It means wind now contributes to 7.6%, or 2,160 terawatt hours, in the international power mix, up from 6.6% last year, an increase of 17% year-on-year. Ember said 2022 is “a turning point in the world’s transition to clean power.” “2022 beat 2020 as the cleanest ever year, as emissions intensity reached a record low of 436 gCO2/kWh [grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated], “the report said. The data revealed that China emerged as the global leader in solar, generating 418 terawatt hours of electricity, accounting for 4.7% of the country’s total electricity. The report said about a fifth (or 55 gigawatts) of all the solar panels installed globally in 2022 were on China’s rooftops, driven mainly by an innovative three-year policy called “Whole-County Rooftop Solar” that started in 2021. Wind power stations of German utility RWE, one of Europe’s biggest electricity companies are pictured in front of RWE’s brown coal fired power plants of Neurath, Germany, Mar. 18, 2022. Credit: Reuters China also retained its position as the world’s largest wind power generator in 2022, with a 9.3% wind share in its electricity mix. Denmark took the lead in wind generation by percentage share, with 55% of its electricity coming from wind power alone, while Chile topped the list of countries with the highest share of solar energy, with 17% solar in its electricity output. In the U.S., the share of wind and solar in total electricity generation increased from 13% in 2021 to 15%, or 644 terawatts hours, in 2022. Around 60% of its electricity still comes from fossil fuels, with a large chunk coming from gas, followed by coal. 80% of the rise in global electricity demand was met by new wind and solar generation in 2022, said the report that collated 2022 electricity data from 78 countries, representing 93% of global electricity demand. “Electricity is cleaner than ever, but we are using more of it,” the report said. The combination of all renewable energy sources and nuclear power represented a 39% share of global electricity generation last year, a new record high. The power sector is the most significant global contributor to planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions. China, the largest CO2 emitter due to coal Among the top 10 power sector emitters, China led the world by three times more than the U.S., the second-biggest carbon dioxide emitter. Ember said China produced the most CO2 emissions of any power sector in the world last year since coal alone made up 61% of China’s electricity mix, which is 17 percentage points fall from 78% in 2000, even though in absolute terms, it is five times higher compared to the start of this century. At 4,694 million metric tons of CO2, China accounted for 38% of total global emissions from electricity generation. However, China alone accounted for 53% of the world’s coal-fired electricity generation in 2022, which showed a dramatic revival in appetite as new coal power plants were announced, permitted, and went under construction dramatically in China. “China is the world’s biggest coal power country but also the leader in absolute wind and solar generation,” said Małgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, the report’s lead author and Ember’s senior electricity analyst. “Choices being made about energy in the country have worldwide implications. Whether peaking fossil generation globally happens in 2023 is largely down to China.” Li Shuo, a senior policy advisor for Greenpeace in East Asia, said China is “the 800-pound gorilla when it comes to the global power sector.” “China has no doubt been leading global renewable energy expansion. But at the same time, the country is accelerating coal project approval,” Li said, adding such a dichotomous relationship “won’t carry the country far to truly decarbonize.” Coal power remained the single largest source of electricity worldwide in 2022, producing 36%, or 10,186 terawatt hours, of global electricity. In 2022, coal power rose by 108 terawatt hours, a 1.1% increase, reaching a record high, largely attributed to the global gas crisis triggered by the Russia-Ukraine war and the revival of coal-fired power stations to meet demand by some countries. Coal use for electricity rose in India by 7.2%, in the E.U. by 6.4%, in Japan by 3.1%, and in China by 1.5%. Gas-fired power generation fell by 0.2%. Overall, that still meant that power sector emissions increased by 1.3% in 2022, reaching an all-time high of 12,431 million metric tons of CO2, the report said. Without renewables, it is estimated that power sector emissions from fossil fuels would have been 20% higher in 2022. Last year may have been the “peak” of electricity emissions and the final year of fossil power growth, with clean power meeting all demand growth this year, according to Ember’s forecast. According to modeling by the International Energy Agency, the electricity sector needs to move from being the highest emitting sector to the first sector to reach net zero by 2040 to achieve economy-wide net zero by 2050. This would mean wind and solar reaching 41% of global electricity by 2030, compared to 12% in 2022. Edited by Mike Firn.

County chief who oversaw destruction of Tibetan Buddhist sites moved to new position

A Chinese official who approved the destruction of a huge Buddha statue in a Tibetan-majority area has been assigned to another position in the same prefecture, Tibetans inside and outside the region said. Wang Dongsheng, former chief of Drago county, now holds an apolitical appointment as director of the Science and Technology Bureau in the Kardze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in China’s Sichuan province, they said. Drago county, called Luhuo in Chinese, lies in Kardze in the historical Tibetan province of Kham. A source in India told Radio Free Asia that Wang was promoted to the position in August 2022. Wang had earlier overseen a campaign of destruction at the sprawling Larung Gar Buddhist Academy in Drago in a move that saw thousands of monks and nuns expelled and homes destroyed. After he took office as Drago county chief in October 2021, Wang directed the demolition of the 30-meter (99-foot) Buddha statue there following official complaints that it had been built too high. Dozens of traditional prayer wheels used by Tibetan pilgrims and other Buddhist worshipers were also destroyed. Officials forced monks from Thoesam Gatsel monastery and Tibetans living in Chuwar and other nearby towns to witness the destruction that began in December 2021. Wang had earlier overseen a campaign of destruction at Sichuan’s sprawling Larung Gar Buddhist Academy in a move that saw thousands of monks and nuns expelled and homes destroyed. “[J]ust within a month of taking the office, he initiated the demolition of Tibetan religious sites in Drago,” said a Tibetan source inside the region who requested anonymity for safety reasons. “Under his leadership the Drago Buddhist school was destroyed.” Hotbed of resistance Since 2008, Drago has been a hotbed of resistance against the Chinese government, prompting interventions by authorities, including significant crackdowns in 2009 and 2012. Beijing views any sign of Tibetan disobedience as an act of separatism, threatening China’s national security. In this satellite image slider, the 99-foot Buddha statue in Drago in the Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture is shown at left sheltered by a white canopy on Nov. 19, 2019. At right is the site on Jan. 1, 2022. Credit: Planet Labs with analysis by RFA Earlier this year, Chinese authorities tightened restrictions on Tibetan residents there, imposing measures to prevent contact with people outside the area, according to sources with knowledge of the situation. Wang’s term as chief of Drago county ushered in a period of heightened assault on Tibetan Buddhism at the hands of the Chinese Communist Party, with the brutal dismantling of important cultural and religious sites. Party leaders who suppress Tibetans and successfully carry out harsh campaigns against the Buddhist minority group are often promoted, said Dawa Tsering, director of the India-based Tibet Policy Institute. “This is the norm, and we can see that happen with Wang Donsheng,” he told RFA. Lui Pang, an executive member of Drago Communist Party, has been appointed as the new county chief, the sources said. Among Drago county’s dozen administrative officials are eight of Chinese origin who hold higher positions, while the remaining four are Tibetans who work as office employees, they said. So far, there’s been a slight easing of the harsh campaigns against Tibetans in the region under the new county chief, said another Tibetan inside the region, who declined to be identified for safety reasons. “Unlike under former chief Wang, if one does not get involved in any political and sensitive issues and incidents, they [authorities] will not make random arrests as such,” the source said. Previously, Wang was appointed deputy secretary of Tibetan-majority Serta county in Kardze, called Ganzi in Chinese, in December 2016, and later served as its county chief. Translated by Tenzin Dickyi for RFA Tibetan. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.

In four languages, young Uyghur gives video testimony about detained uncle

For Nefise Oghuz, giving testimony about the illegal imprisonment of her uncle and what she says is the genocide of Uyghurs in western China was her “duty.” The 20-year-old Uyghur student provided statements in four languages — Uyghur, English, Mandarin and Turkish — on social media platforms, including Twitter and Facebook, about how police in Urumqi, capital of western China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, arrested her uncle, Alim Abdukerim, 33, at his home on Aug. 28, 2017. “I dared to share this video testimony as I could not bear the sufferings of my people facing genocide,” she told Radio Free Asia. “I could not accept the fate of my uncle and that of millions of Uyghurs in the concentration camps, and I felt terrible for my nephew, who had not seen his father even once after he was born.” Abdukerim’s family did not know his whereabouts for two years, though Oghuz later obtained information that he was in prison in Korla, known as Ku’erle in Chinese and the second-largest city in Xinjiang, two years after he was taken away. “My innocent uncle has been in jail for the past six years,” Oghuz says in the multilingual videos. “I demand the Chinese government release my uncle, Alim Abdukerim, immediately.” ‘I could not bear this injustice’ “My uncle Alim Abdulkerim has been detained in Xinjiang for six years because he is Uyghur. He hasn’t been able to see his son, Abdulkerim, who is now six years old. We believe he is innocent and appeal to the Chinese government to release him and reunite him with his family. pic.twitter.com/EdWEMkhVri — Nefise Oğuz (@NefiseOguzz28) April 2, 2023 The videos have received widespread attention from Uyghurs in the diaspora as well as an outpouring of reactions on social media. “Since we could not get any information about him, I could not bear this injustice,” Oghuz told Radio Free Asia by phone from Istanbul, where she and her family have lived since 2015. “So, I gave this testimony. For the past years, we kept mum, fearing that our testimony would cause harm to other relatives in our homeland,” said the sophomore majoring in English journalism at Turkey’s Istanbul University, who studied in bilingual classes in Xinjiang until middle school. “Although I have not openly advocated for my uncle previously so as not to cause trouble for my relatives back home, I have advocated for my uncle through various channels in a more discreet way,” she said. “Realizing my uncle had suffered too long, we lost our confidence in the Chinese government’s justice and began openly demanding his release.” Chinese police detained Abdukerim shortly after he married amid a larger crackdown on Uyghurs beginning in 2017 during which authorities arbitrarily detained ordinary and prominent Uyghurs, such as businesspeople, writers, artists, athletes and Muslim clergy members into “re-education” camps. China has claimed that the camps were vocation training centers set up to prevent religious extremism and terrorism in the restive mostly-Muslim region. But those who survived the camps say Uyghurs there were subjected to torture, sexual assault and forced labor. The U.S. government, the European parliament and the legislatures of several Western countries have declared that the Chinese government’s abuses against the Uyghurs amount to genocide and crimes against humanity. A report issued by the U.N.’s human rights body has said that the camp detentions may constitute crimes against humanity. . Reason for arrest unclear Abdukerim, who has a young son he’s never seen, was a computer engineer responsible for managing computer and internet-related business at a family-run company called Halis Foreign Trade Ltd. He and Oghuz grew up together. Oghuz said she tried to obtain information about him from relatives in Xinjiang and from Chinese social media sources. “We don’t know why the Chinese government arrested him,” she said. “He had never been abroad. I think the Chinese authorities detained him for being Uyghur and Muslim.” Following Abdukerim’s arrest, the family’s company closed its doors. His crime and the length of his sentence remain unknown, though Oghuz learned that he is being held at a prison in Korla that operates under the auspices of the Xinjiang Construction and Production Company, a state-owned economic and paramilitary organization also known as Bingtuan. His prisoner number is 3153. “I hope the Chinese government releases my uncle and allows him to meet his son,” she said. “It’s OK if I don’t see him, but his son needs to see his father. I will not stop being my uncle’s voice until the Chinese authorities release him.” Different languages Oghuz said she presented testimony in Turkish, hoping that the Turks would pay attention to the sufferings of the Uyghurs, thousands of whom live in the diaspora in the southern European country. She gave it in English, hoping that the international community would also pay attention, at a time when Uyghur rights groups are calling for concrete measures to hold China to account for its actions in Xinjiang. And she gave testimony in Chinese to try to force the Chinese government to respond to her demand. “For those who think they cannot give testimony in foreign languages, they may provide it in the Uyghur language,” Oghuz said. “Your testimony will eventually cause anxiety among the perpetrators,” she said. “The Chinese will see your testimony and worry that if more people like you speak up, they will expose their crime to the broader global community.” Translated by RFA Uyghur. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.