Category: East Asia

Congressional hearing examines Chinese repression in Tibet

During a congressional hearing Tuesday on China’s growing repression in Tibet, U.S. Rep. Zach Nunn likened Beijing’s policy to an idea from an ancient Chinese essay about political strategy – sacrificing the plum tree to preserve the peach tree. “What they mean by this is that you can sacrifice in the short-term those who are the most vulnerable for the strength of those who are in power,” said Nunn, a Republican from Iowa, referring to a phrase from Wang Jingze’s 6th-century essay, The Thirty-Six Stratagems. “We are seeing this played out constantly in the autonomous state of Tibet today by the Chinese government,” said Nunn, a former intelligence officer. The hearing examined China’s increasing restrictions on linguistic and cultural rights in Tibet, its use of what commission members call “colonial boarding schools” for Tibetan children and attempts to clamp down on Tibetans abroad. It was held as both houses of Congress consider legislation that would strengthen U.S. policy to promote dialogue between China and Tibetan Buddhists’ spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, or his representatives. The Dalai Lama and the Central Tibetan Administration, Tibet’s government-in-exile in Dharamsala, India, have long advocated a middle way approach to peacefully resolve the issue of Tibet and to bring about stability and co-existence based on equality and mutual cooperation without discrimination based on one nationality being superior or better than the other. There have been no formal talks between the two sides, and Chinese officials have made unreasonable demands of the Dalai Lama as a condition for further dialogue. Chinese communists invaded Tibet in 1949, seeing the region as important to consolidate its frontiers and address national defense concerns in the southwest. A decade later, tens of thousands of Tibetans took to the streets of Lhasa, the regional capital, in protest against China’s invasion and occupation of their homeland. People’s Liberation Army forces violently crackdown on Tibetan protesters surrounding the Dalai Lama’s summer palace Norbulingka, forcing him to flee to Dharamsala, followed by some 80,000 Tibetans. U.S. bill on Tibet The Promoting a Resolution to the Tibet-China Conflict Act, introduced in the House in February and in the Senate in December 2022, also direct the U.S. State Department’s Special Coordinator for Tibetan Issues, currently Uzra Zeya, to ensure government statements and documents counter disinformation about Tibet from Chinese officials, including disinformation about the history of Tibet, the Tibetan people and Tibetan institutions. In recent years, the Chinese government has stepped up its repressive rule in Tibet in an effort to erode Tibetan culture, language and religion. This includes the forced collection of biometric data and DNA in the form of involuntary blood samples taken from school children at boarding schools without parental permission. Penpa Tsering, the leader, or Sikyong of the Central Tibetan Administration, testified virtually before the commission, that reports by the United Nations and scholarly research indicates that the Chinese government’s policy of “one nation, one language, one culture, and one religion” is aimed at the “forcible assimilation and erasure of Tibetan national identity.” Rep. Zach Nunn participates in a congressional hearing on Tibet in Washington, D.C., Tuesday, March 28, 2023. Credit: Gemunu Amarasinghe/RFA As examples of the policy, Tsering pointed to the use of artificial intelligence to surveil Tibetans, the curtailing of information flows to areas outside the region, interference in the selection of the next Dalai Lama, traditionally chosen based on reincarnation, the forced relocation of Tibetans to Chinese developed areas inside the region and “unscrupulous” development that damages the environment. “If the PRC [People’s Republic of China] is not made to reverse and change its current policies, Tibet and Tibetans will definitely die a slow death,” Tsering said. American actor and social activist Richard Gere, chairman of the International Campaign for Tibet, told the commission that the United States must “speak with a unified voice” and engage European like-minded partners against China’s repression in Tibet. China’s pattern of repression in Tibet “gives reason for grave concern and it increasingly expands to match the definition of crimes against humanity,” Gere said. Forced separation China’s assault on Tibetan culture includes the forced separation of about 1 million children from their families and putting them in Chinese-run boarding schools where they learn a Chinese-language curriculum and the forced relocation of nomads from their ancestral lands, he said. Lhadon Tethong, director of the Tibet Action Institute, an organization that uses digital communication tools with strategic nonviolent action to advance the Tibetan freedom movement, elaborated on the separation of school children from their families. Agents of the Chinese government are using manipulation and technologies of oppression “To bully, threaten, harass and intimidate” members of the Tibetan diaspora into silence, said Tenzin Dorjee [right] a senior researcher and strategist at the Tibet Action Institute. Richard Gere, chairman of the board of the rights group International Campaign for Tibet [left] and Lhadon Tethong, director of the Tibet Action Institute, also spoke at the congressional hearing in Washington, D.C., Tuesday, March 28, 2023. Credit: Gemunu Amarasinghe/RFA “[Chinese President] Xi Jinping now believes the best way for China to conquer Tibet is to kill the Tibetan in the child,” she told the commission. “He’s doing this by taking nearly all Tibetan children away from their families and from the people who will surely transmit this identity to them — not just their parents, but their spiritual leaders and their teachers — and he’s handing them over to agents of the Chinese state to raise them to speak a new language, practices a new culture and religion — that of the Chinese Communist Party.” Tethong’s colleague, Tenzin Dorjee, a senior researcher and strategist at the Tibet Action Institute, discussed how China has extended its repressive policies beyond Tibet to target Tibetan diaspora communities in India, Nepal, Europe and North America through surveillance and harassment. Formal and informal agents of the Chinese government use manipulation and technologies of oppression “To bully, threaten, harass and intimidate” members of the diaspora into silence, he said. “The best way to counter China’s transnational repression is to…

U.S. sanctions two people, six entities for supplying Myanmar with jet fuel

The United States Treasury Department has announced additional sanctions on Myanmar to prevent supplies of jet fuel from reaching the military in response to airstrikes on populated areas and other atrocities. The sanctions came just days before Myanmar celebrated its 78th Armed Forces Day on Monday. The announcement on Friday targeted two individuals, Tun Min Latt and his wife Win Min Soe, and six companies including, Asia Sun Trading Co. Ltd., which purchased jet fuel for the junta’s air force; Cargo Link Petroleum Logistics Co. Ltd., which transports jet fuel to military bases; and Asia Sun Group, the “key operator in the jet fuel supply chain.” The statement said that since the Feb. 1, 2021 coup that overthrew the country’s democratically elected government, the junta continually targeted the people of Myanmar with atrocities and violence, including airstrikes in late 2022 in Let Yet Kone village in central Myanmar that hit a school with children and teachers inside, and another in Kachin state that targeted a music concert and killed 80 people. According to a March 3 report by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, junta-led airstrikes more than doubled from 125 in 2021 to 301 in 2022. Those airstrikes would have been impossible without access to fuel supplies, according to reports from civil society organizations, Friday’s announcement said. “Burma’s military regime continues to inflict pain and suffering on its own people,” said Under Secretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Brian E. Nelson. “The United States remains steadfast in its commitment to the people of Burma, and will continue to deny the military the materiel it uses to commit these atrocities.” Helicopters and other aircraft are displayed at the Diamond Jubilee celebration of Myanmar’s air force, Dec. 15, 2022. on diamond Jubilee celebration of the Military Air Force. Credit: Myanmar military The announcement named Tun Min Latt as the key individual in procuring fuel supplies for the military, saying he was a close associate of the junta’s leader Sr. Gen Min Aung Hlaing. Through his companies, he engaged in business to import military arms and equipment with U.S. sanctioned Chinese arms firm NORINCO, the announcement said. “The United States continues to promote accountability for the Burmese military regime’s assault on the democratic aspirations of the people of Burma,” said U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken in a separate statement. “The regime continues to inflict pain and suffering on the people of Burma.” The additional sanctions by the U.S. aligned with actions taken by Canada, the United Kingdom and the European Union, Blinken said. Cutting bloodlines “I am very thankful to the United States for these sanctions,” Nay Phone Lat, the spokesperson for Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government, told Radio Free Asia’s Burmese Service. “I know that sanctions are usually done one step after another. It’s like cutting the bloodlines of the military junta one after another.” He said that the shadow government was trying to cut each route of support for the junta, including jet fuel, one after another. “[The junta’s] capability of suppressing and killing innocent civilians will be lessened,” he said. Banyar, the director of the Karenni Human Rights Group, which was among 516 civil organizations that made a request in December to the United Kingdom to take immediate action to prevent British companies from transporting or selling jet fuel to the Myanmar military junta, told RFA that the U.S. sanctions would have many impacts. “If you look at the patterns, the number one thing is that taking action against these companies that provide services to the junta directly discredits the military junta,” he said. “And the sanctioned companies are also punished in some ways. We can say that this is also a way to pressure other companies to not support the military junta.” But Myanmar has been sanctioned before to little effect, said Thein Tun Oo, executive director of Thayninga Institute for Strategic Studies, which is made up of former military officers. “No matter what sanctions are imposed, there will not be any major impact on Myanmar as it has learned how to survive through sanctions. There may be a little percentage of economic slowdown but that’s about it,” he said. The military has many options when it comes to buying jet fuel, said Thein Tun Oo. “We are not buying from just one source that they have just sanctioned, we can buy from all other sources. Jet fuel is produced from not just one place,” he said. “If we want it from countries in affiliation with the United States, we may have problems but the United States is not the only country that produces jet fuel, so there is no problem for the Myanmar military.” The military could look to China, Thailand, India or Russia for jet fuel if necessary, political analyst Than Soe Naing told RFA. “The sanctions imposed against the Myanmar military are little more than an expression of opinion, in my point of view, as they cannot actually restrict the junta effectively from getting what it needs,” said Than Soe Naing. “The reason is that the three neighboring countries and Russia can still supply the junta with the jet fuel from many other routes.” Ze Thu Aung, a former Air Force captain who left the military to join an armed resistance movement after the coup, told RFA that U.S. sanctions are not enough to stop the junta. “Whatever sanctions [Washington] imposes, the military junta can still survive as it is still in control of its major businesses such as the jade, oil and natural gas industries,” he said. “They have enormous funds left. They have Russia backing them as well. China is supporting them to some extent, too.” Translated by Myo Min Aung. Edited by Eugene Whong and Matt Reed.

Hong Kong police force protesters to wear numbered badges, march in cordon

Participants in the first public protest in Hong Kong since a draconian national security law took effect were forced to wear badges and walk within a police cordon last weekend. A few dozen people protesting a proposed land reclamation project and garbage processing facility marched in the eastern district of Tseung Kwan O on Sunday, wearing numbered lanyards and walking within a security ribbon in a manner reminiscent of an elementary school outing. The protest was the first to go ahead since the ruling Chinese Communist Party imposed a national security law on Hong Kong in July 2020, ushering in a citywide crackdown on public dissent and peaceful opposition that has seen dozens of former opposition lawmakers and pro-democracy activists stand trial for “subversion” for holding a primary election. But protesters said the restrictions imposed on them weren’t acceptable. “To be honest, a lot of people including myself feel that wearing numbered lanyards and walking inside a security tape is actually pretty humiliating,” political activist and former Democratic Party member Cyrus Chan told Radio Free Asia at the protest. “A lot of us have years of experience as marshals in the [formerly annual] July 1 demonstrations and the [now-banned] Tiananmen massacre vigils,” he said. “I’ve never seen anything like this before.” “We feel as if we are living in a whole new world,” Chan said. “As to whether that’s a brave and beautiful new Hong Kong in which we are free, or one in which we are subject to all manner of restrictions, I hope the government will consider this question.” Protesters had to wear these numbered lanyards during their march in Hong Kong on March 26, 2023. Credit: AFP Dragged around ‘like livestock’ Police earlier gave permission – via a “letter of no objection” – for a women’s rights march in honor of International Women’s Day, but organizers later canceled the event amid threats from police that they would arrest key activists. Sunday’s protest also received a letter of no objection after organizers applied for permission to hold a march of up to 300 people, but with a number of conditions attached, including individually numbered lanyards for each participant and a cordon preventing anyone from joining the protest if they hadn’t been there from the start. “Some lawbreakers may mix into the public meeting and procession to disrupt public order or even engage in illegal violence,” the police letter said by way of explanation. Participants were also told they couldn’t wear masks or cover their faces. “I really don’t like wearing a number, being numbered,” one participant told Radio Free Asia. “It really places limits on the spontaneity of the event, and makes people wary of taking part.” “We were dragged around inside this cordon the whole time like livestock,” they said. “It was really strange.” Former pro-democracy lawmaker Ted Hui, now living in Australia, said the mask bans first emerged as part of “emergency measures” taken to curb the 2019 protest movement, which had massive popular support for its resistance to the erosion of Hong Kong’s promised freedoms, and its demand for fully democratic elections. Protesters walk within a cordon line wearing number tags during a rally in Hong Kong on March 26, 2023. Credit: Associated Press Color revolution fears Beijing has dismissed the protest movement as the work of “hostile foreign forces” who were trying to foment a “color revolution” in Hong Kong through successive waves of mass protests in recent years. The government last week ordered the takedown of a digital artwork bearing some of the protesters’ names. “There was a lot of opposition [to the mask ban] back then,” Hui said. “Yet they are still using this law three years later, which tells us that the Hong Kong government hasn’t learned any lessons [from the 2019 protest movement].” Hui said the new system is similar to “real-name” requirements typically used to track people’s activities in mainland China, and will likely put participants at greater risk of official reprisals. “The Hong Kong government will definitely be retaliating against participants,” he said. “They may or may not prosecute them, or they could investigate them, or confiscate their travel documents.” “That’s the sort of thing people have been accustomed to seeing in Hong Kong over the past three years,” Hui said, adding that the freedoms of association, assembly and expression enshrined in the city’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, now exist in name only. A spokesperson for the Democratic Party said the whole point of a protest is to allow for the airing of public opinion, so the number of participants shouldn’t be limited. The government-run Independent Police Complaints Council said the conditions placed on protesters were “understandable,” and said not every demonstration would necessarily be subject to the same restrictions in future. Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Matt Reed.

For founder’s birthday, North Korean cities ordered to decorate streets with flowers

To celebrate the April 15 birthday of North Korea’s founder Kim Il Sung, authorities have ordered cities and towns to decorate the streets with flowers for the first time in three years, two sources in the country told Radio Free Asia. The holiday is a big deal in North Korea, where it is known as the “Day of the Sun.” Together with the “Day of the Shining Star,” the Feb. 16 birthday of his son, Kim Jong Il, the holiday perpetuates the personality cult surrounding the Kim family, which has ruled the country for three generations. Normally, the capital of Pyongyang and other major cities are decorated with flowers and new propaganda paintings and slogans are splashed across the cities ahead of the Day of the Sun, but that stopped about three years ago in most places due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Authorities want to bring the flowers back this year, even in rural towns and villages, a company official from Pochon county in the northern province of Ryanggang told RFA’s Korean Service Wednesday on condition of anonymity to speak freely. “It seems like an attempt to change the mood in the province, which has gone sour due to ongoing food shortages and a lack of daily necessities,” the source said. North Korea’s food situation was already dire prior to the pandemic but it got worse when authorities shut down the Sino-Korean border and suspended all trade for more than two years. Although rail freight between the northeast Asian neighbors has resumed, North Korea has not yet fully recovered. Flowers play an important role in the Days of the Sun and Shining Star because both of the late leaders have flower species named after them, a strain of orchid named Kimilsungia, and a strain of begonia named Kimjongilia, although it wasn’t clear if this year’s decoration orders called for either species. People walk in the street decorated with colorful flowers on the occasion of the 110th birth anniversary of late North Korean leader Kim Il Sung, in Pyongyang, April 15, 2022. Credit: Associated Press Paper flowers to make up for shortfall To adorn the streets of Pochon county with flowers, the landscaping management office has had to get creative, making paper flowers to make up for a shortfall of real ones, the source said. “They are growing as many fresh flowers as possible to decorate the center of the town and supplement them with paper flowers if they don’t have enough,” said the source. “The landscaping management office operates a small vinyl greenhouse but it is difficult to keep the temperature constant, so they have not been able to grow many flowers.” The greenhouse’s temperature is maintained by firewood brought in by employees from the mountainside, it hasn’t been working well. “The office therefore distributed five flower pots to each employee who lives in decent conditions to grow the flowers in their homes,” the source said. Chongjin scramble In Chongjin, one of the country’s largest cities, authorities are scrambling to grow flowers fast enough. They haven’t had to prepare flowers for the Day of the Sun in three years, and the order took them by surprise, a resident there told RFA on condition of anonymity to speak freely. “This year the Central Committee issued instructions to decorate the roads with flowers to create a festive atmosphere, so the landscaping management office of each district of the city, as well as the city’s flower office are struggling to prepare fresh flowers,” the second source said. “Keeping the right temperature inside the greenhouse is key to growing flowers quickly so that they can be ready for April 15th,” the second source said. “Currently, landscaping management offices and flower offices are spending money that they barely have to buy firewood from the market to maintain the temperature.” This could turn out to be problematic down the road, as the central government has not told the local office that they would finance their firewood purchases, the second source said. Most residents could care less about the festivities or the flowers, the second source said. “[They] are busy making a living every day have no time to appreciate or think about flowers,” he said. “The authorities’ order to set the holiday atmosphere with flower decorations for the ‘Day of the Sun’ is just a makeshift measure to try to end the dark atmosphere caused by hardships in life.” Translated by Claire Shinyoung Oh Lee. Edited by Eugene Whong and Malcolm Foster.

Chinese coast guard ship chased out of Vietnam waters

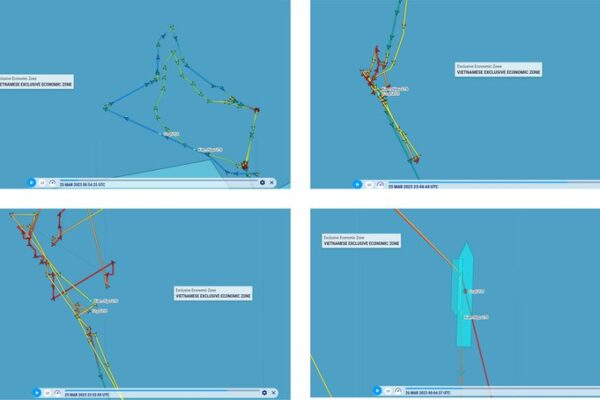

A Chinese coast guard ship and a Vietnamese fisheries patrol boat apparently had a tense encounter during the weekend in the South China Sea, coming as close as 10 meters to each other, according to data from Marine Traffic, a ship-tracking website. The data, based on the ships’ automatic identification system (AIS) signals, shows that the China Coast Guard ship, CCG5205, and Vietnam’s Kiem Ngu 278 came “crazy close” to one another at around 7 a.m. on Sunday local time (midnight UTC), said a researcher based in California. As of Monday afternoon (local time), the CCG5205 was operating in Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone after it left Vietnam waters where the Kiem Ngu 278 had been pursuing the considerably larger Chinese ship since March 24, tracking data showed. At one point the two ships were less than 10 meters (32.8 feet) apart, according to Ray Powell, the Project Myoushu (South China Sea) lead at Stanford University, who first spotted the incident at sea. “The Vietnamese ship was pretty bold given the difference in size – the Chinese ship is twice the size of the Vietnamese ship,” Powell said. “It must have been a very tense engagement.” The incident occurred some 50 nautical miles (92.6 kilometers) south of Vanguard Bank, a known South China Sea flashpoint between Vietnam and China. About 90 minutes later, the Chinese ship left Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) where it had been since Friday evening. An EEZ gives a state exclusive access to the natural resources in the waters and in the seabed. Ship-tracking data shows Vietnam’s Kiem Ngu 278 was closely following the Chinese coast guard vessel CCG5205. [Marine Traffic] Last month, the same China Coast Guard ship was accused of approaching about 150 yards (137 meters) from a Philippine Coast Guard ship and pointing a laser at the crew, causing temporary blindness to them. On Feb. 6, the Philippine Coast Guard said that the Chinese ship had “directed a military-grade laser light” twice at the BRP Malapascua, which was on its way to deliver food and supplies to the troops stationed at the Second Thomas Shoal in the South China Sea. Manila lodged a diplomatic protest and the U.S. State Department issued a statement supporting “our Philippine allies.” Beijing rejected the allegation, saying the Philippine ship had “intruded into the waters” off the Spratly Islands “without Chinese permission” and the Chinese coast guard ship had “acted in a professional and restrained way.” ‘Too close for comfort’ In the Sunday encounter, Marine Traffic’s past track showed the Chinese CCG5205 and the Vietnamese Kiem Ngu 278 were so close that they could have collided. “Ten meters between ships is really too close for comfort,” said Collin Koh, a Singapore-based regional maritime analyst. “Depending on the sea state, the risk of collision is fairly high,” Koh told Radio Free Asia (RFA). A retired Vietnamese Navy senior officer, who spoke to RFA on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the topic, said the two ships must have narrowly escaped a collision because they were sailing in opposite directions and at a very slow speed. “If they were heading to the same direction a collision would have not been avoidable as the distance is too close and too dangerous,” he said. Chinese ships had deliberately rammed Vietnamese patrol ships in the past, he added, but not in recent years. The CCG5205 left Sanya, in Hainan island, for the current mission on March 11 and entered Vietnam’s EEZ the first time on March 12. It then moved to the overlapping area between claimant states in the South China Sea and Malaysia’s EEZ before entering Vietnam’s EEZ again on March 21 for a couple hours and for the third time on March 24 when the Kiem Ngu 278 chased it. At around midnight UTC on March 26, Vietnam’s Kiem Ngu 278 and China’s CCG5205 were dangerously close. [Marine Traffic] The Kiem Ngu 278, officially named Vietnamese Fisheries Resources Surveillance ship KN-278, is homeported in Vung Tau, south of Ho Chi Minh City. It left base on March 13 and had been following the Chinese vessel closely since. In July 2021, the Kiem Ngu 278 was following another Chinese coast guard ship, the CCG5202, which Vietnam accused of harassing its gas-exploration activities. Six parties hold claims to parts of the South China Sea and its natural resources but China’s claim is the biggest and Beijing has been trying to hinder other countries’ oil and gas activities in the waters inside its self-claimed nine-dash line. A 2,600-ton Chinese survey vessel, the Haiyang Dizhi Si Hao, had lingered inside Vietnam’s EEZ from March 9 until March 25, when it switched off its AIS, according to data from Marine Traffic. Its whereabouts are currently unknown.

Impacts of Chinese DWF on the South China Sea littoral states

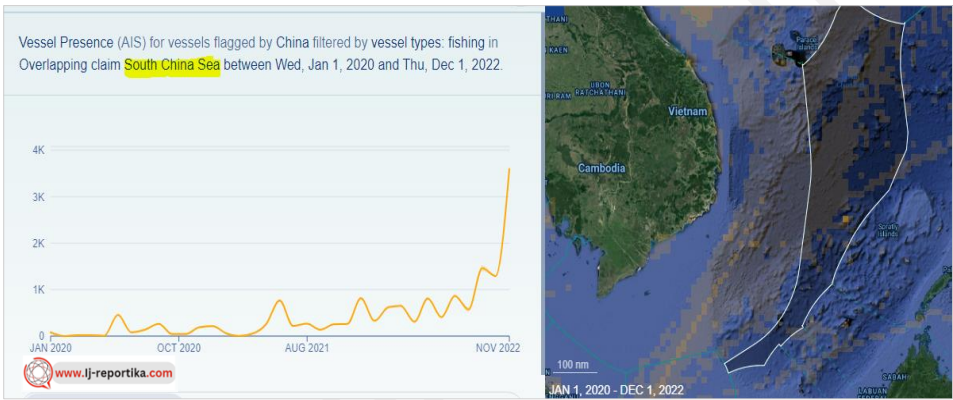

Historically speaking, China has claimed the majority of the South China Sea as part of its territory which includes the Paracel Islands, Spratly islands, Pratas Island, Vereker Banks, Macclesfield Bank, and the Scarborough shoal. All these places fall under the much disputed “nine-dash line” markings which are based on a 1947 map. In 1946, a map having eleven dashes or dots was published by the Chinese government. However, two dashes in the Gulf of Tonkin were later removed when a treaty was signed with Vietnam. Many of the Chinese neighboring states including Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam have tried to claim these lands as their own, rejecting the questionable map. The main issue with the “nine-dash line” lies in the fact that it is an arbitrary collection of dashes without specific coordinates. Based on this map, China asserts rights to more than 80% of the South China Sea. Any official explanation regarding its origin or even its precise delimitation has never been provided by China. On top of that, the regions claimed by China as part of its territory directly lie in conflict with Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of multiple countries in the area like Brunei, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Taiwan, and the Philippines. Despite protests by these countries, China has deployed its distant-water fishing fleet in the EEZs of Vietnam and the Philippines. According to data reported by IJ-Reportika, China has fished for over a million hours last year through its Long-liners, Tuna purse seines, Squid jiggers, and Trawlers. While the Chinese DWF activities are not very significant in the South China Sea, overfishing and climate change have led to the depletion of marine resources in the area. Since 2000, the catch rates have declined by 70% and large fish stocks have depleted by 90% in the region. Despite the declining marine resources in the region, it is surprising that Chinese activities have increased in the area while banning the fishing activities of other countries in the region. Every year since 1999, China imposes a ban on fishing activities from May to August in the area including the Gulf of Tonkin and Paracel islands which are disputed territories. Vietnam condemned this ban and released a statement saying, “Vietnam requests China to respect Vietnam’s sovereignty over Paracel islands…without complicating the situation towards maintaining peace, stability, and order in the East Sea.” The Philippines has shown contempt for the ban saying “This ban doesn’t apply to us. Our fisherfolk are encouraged to go out and fish in our waters in the West Philippine Sea.” Interestingly, this ban does not apply to Chinese fishermen who have an official license to fish in the contested waters. It is worth noting that the Chinese DWF vessels are not only there to fish but also operate as de facto maritime militias under the control of the Beijing authorities. There have also been reports of construction activities being conducted by the Chinese in the Spratly islands over the past decade. Legally speaking, this area is not a part of China’s territory, but that has not stopped the Chinese from building reefs, islands, and other formations and even militarizing them with ports, runways, and other infrastructure. According to multiple media reports and satellite imagery, in the past decade, they have carried out construction activities at four unoccupied features in the Spratly islands. A Chinese maritime vessel was seen offloading a hydraulic excavator which is used in land reclamation projects. It is also reported that new land formations have appeared above water in the Eldad Reef of the northern Spratly islands, which were only exposed during the high tide. The images show large holes, debris piles, and excavator tracks at the site. Similar activities have taken place on Panata Island in the Philippines, where a new perimeter wall was seen around a feature. These activities have resulted in the expansion of some sand bars and other formations in the area by at least ten times. Although any reclamation activities by China are in direct conflict with the 2016 ruling by the International Tribunal, other nations in the region are forced to undertake their own reclamation work. According to a report by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, Vietnam has expanded dredging and landfill work at several of Spratly outposts and have created roughly 1.7 sq. km of new land in 2022. Following the reports of landfill work and mooring by Chinese ships in the area, the Philippines have also increased their military presence in the region. As China continues to foray into the disputed waters despite warnings, it is interesting to see the South China Sea through the lens of strategic geopolitical location. With the growing tension in the area, China has been investing more and more in the Navy and coast guard to defend its claim over this territory and increased its presence in the region through fishing fleets. The area could prove to be of significant military importance if the US decided to jump into the regional war, supporting Taiwan’s fight for sovereignty. It is safe to say that China won’t give up control of the region any time soon, even if it means upsetting a few powerful economies.

Impacts of Chinese DWF on the Asian countries

China’s Distant-water fishing fleet, which operates on the high seas and also in the Exclusive Economic Zones of other countries, is the biggest fleet in the world with an estimated 2,700 ships. The distant-water fishing sector is infamous for being secretive and unregulated as many countries fail to publish their fishing data. This is not surprising given the fact that it is often found guilty of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing practices, targeting prohibited species and causing irreversible environmental damage as well as intelligence gathering, espionage, and space tracking. The presence of illegal Chinese DWF vessels is felt all over the world, but it is particularly worse in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Countries in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), South China Sea region, as well as East Asian countries, and Russia, are all victims of IUU fishing and violation of EEZ by Chinese vessels. Despite the fact that the IOR has the presence of many countries in the region, the Chinese DWF fleets have increasingly become a hazard, especially in the Northern Indian Ocean region (NIOR). The NIOR is an important region as most of the world’s maritime traffic passes through it, hence the presence of dubious Chinese DWFs raises concern. The NIOR, which comprises countries like India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Iran, and Oman, is seeing a surge in unregistered Chinese fishing vessels. According to the Indian Navy, they monitored more than 392 Chinese IUU fishing incidences in the Indian Ocean in 2021 compared to 379 in 2020. It is also reported that spy ships disguised as fishing boats are being used by the Chinese to gather intelligence data and spy on assets of other countries, including India’s Andaman and Nicobar islands. While the other countries have seen a significant increase in Chinese activities in their EEZ, in Pakistan on the other hand, the presence of China’s DWF is minimal and on a downward slope. Could it be a benefit of being a trading partner and ally to China? The island nations in the NIOR like Sri Lanka and Maldives have reported the presence of Chinese DWF vessels such as squid jiggers, trawlers, and long liners that fish in the area before moving to other target areas like Oman in the Arabian Sea. The Chinese vessels in Oman, according to our report, often misuse the Iranian flag as a disguise and are engaged in fishing at an industrial scale. This activity has increased exponentially since 2016. A similar issue persists in Iran where the trawlers are taking close to 46,000 tons of commercial fish, as stated in a report from the Iranian parliament. This is leading to depletion in numbers of protected species and dolphins which are killed by commercial dragnets. Reflagging themselves under Iran’s flags, these trawlers fish for seahorses, who are then dried and powdered to be used in Traditional Chinese Medicines (TCM). Eastern Indian Ocean Region In the eastern IOR, nations like Indonesia and Malaysia are sea-based economies that are highly dependent on fishing. As Chinese DWFs with huge capacities stay longer in the area, the local fishermen are finding it tough to earn their daily bread and butter. Indonesian laborers, who work on some of these fishing vessels, suffer racial abuse and exploitation at the hands of their Chinese managers. It has been reported that between 2019 and 2020, 30 Indonesian fishermen died onboard Chinese long-haul fishing boats because of substandard food, dangerous drinking water, and excessive working hours. Due to its close proximity to China, East Asian nations like Japan and South Korea are the most vulnerable and the most impacted by Chinese vessels. South Korea has also reported Chinese-flagged ships fishing in their EEZ. The western region neighboring China is the worst affected with over 300K hours of illegal fishing done by Chinese vessels. The governments of South Korea and China have held several talks to smooth out this issue since the beginning of the last decade, which have failed to bear any fruit. Chinese coast guard ships and fishing vessels have been making attempts to change the status quo by coercion in the Senkaku islands. Chinese ships mounted with artillery approached Japanese ships in the Japanese territory. The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs has released a statement saying, “The Senkaku Islands are indisputably an inherent part of the territory of Japan in light of historical facts and based upon international law, and are, in fact, effectively under the Japanese control… It is a violation of international law for the China Coast Guard ships to act making their assertions in Japanese territorial waters around the Senkaku Islands, and such acts will not be tolerated.“ Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Quite surprisingly, Chinese trawlers were also spotted in the EEZ of Russia. The vessels have done over a million hours of dark surfing in the Russian far-east. While many countries have strongly opposed the fishing activities by Chinese vessels, some have taken strict measures. Indonesia, for example, has sunk many Chinese ships in the last four years which were dangerously close to their land boundary. The Quad, comprising India, Australia, Japan, and the US have announced a major regional effort under the ambit of Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness (IPDMA) aimed to provide more accurate maritime pictures of activities in the region. As the Chinese distant-water fishing activities are growing rapidly and unsustainably all around the world, it is depleting global fish stocks and disrupting the marine ecosystem. Moreover, it is increasingly becoming a source of diplomatic and environmental tensions with other nations. Hence, it has become imperative to introduce laws, policies, and strict measures to keep it in check.

One of the biggest rebellions in the history of China

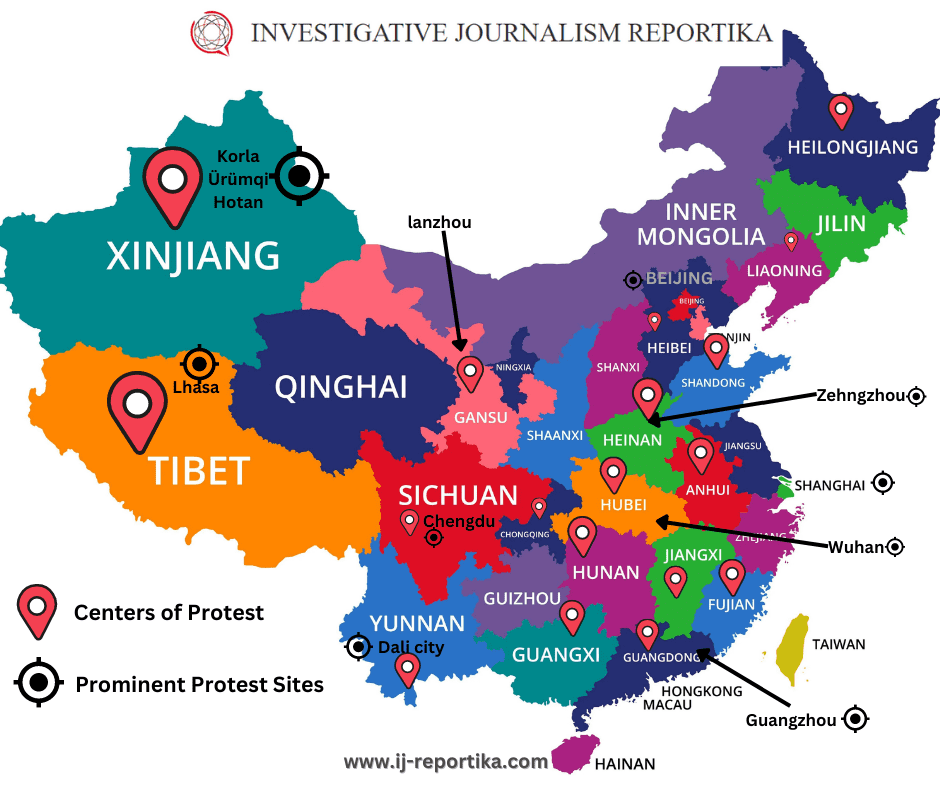

From Lhasa and Xinjiang to Beijing and Shanghai, protests have erupted across China and have taken the shape of a colossal rebellion.

Labor Uprising In China’s Zhengzhou against Zero COVID & Apple’s Foxconn factory

A labor uprising over COVID-19 restrictions and contract violations by Apple at Foxconn’s iPhone factory in central China is unfolding in Zhengzhou. The government-deployed security officers are trying to suppress the uprising with violence as shown in the videos circulating on Chinese social media. #LaborUprisingInChina trending on Social Media #LaborUprisingInChina trended for hours in many parts of the world on 23rd November 2022. People on social media showed sympathy towards the suffering laborers at the Foxconn iPhone factory. What is happening in Zhengzhou? Laborers and workers at Foxconn’s Zhengzhou factory held protests on the factory campus, where they have had to stay since a closed-loop system was announced to counter the spread of COVID-19 without compromising productivity under the Zero Covid policy. Videos of the violence in Zhengzhou showed masked laborers facing off police in protective suits. The authorities have used force and severely injured many of them. The violence comes as China tightens once again its COVID-19 measures, making it the only major economy still subscribed to full lockdowns to face virus outbreaks. China’s coronavirus measures have triggered domestic dissent this year. We have covered over 450 protests in China this year. However, near the end of the year, China is beholding a massive labor uprising from one of the most downtrodden classes in the manufacturing hub of the world. Local authorities are continuing to stick to the “zero-Covid strategy” championed by the central government in Beijing. The easing of the restrictive measures imposed on large factory compounds like the Foxconn factory in Zhengzhou is unlikely. Why are laborers at Foxconn protesting? Some workers said they were informed that the bonus that was initially promised to them would be delayed, and the situation in the dormitory, where workers who have been there for weeks were mixed with the newly hired workers, enhances the risk of them being exposed to the coronavirus. Videos of many people leaving Zhengzhou on foot had gone viral on Chinese social media earlier in November, forcing Foxconn to step up measures to get its staff back. To limit the fallout, the company said it had quadrupled daily bonuses for workers at the plant this month. On Wednesday, workers said that Foxconn failed to honor their promise of an attractive bonus and pay package after they arrived to work at the plant. Numerous complaints have also been posted anonymously on social media platforms — accusing Foxconn of having changed the salary packages previously advertised. “the allowance has always been fulfilled based on contractual obligation” Foxconn said in a statement on Wednesday Ij-Reportika reached out to one of the laborers who protested on the 23rd. Under the condition of anonymity, he said, “We are made to live in miserable conditions, we don’t have any rights, we don’t want to work in the Apple factory day in and day out with all our livelihoods destroyed. We are at high risk of getting infected by the virus and on top of all this our contracts are violated and our payments and bonuses are stuck. They offered me 8000 Yuan to leave and go back to my hometown. But I refused to take it!! Protesting Labor at Zhengzhou

Amid growing protests, China cautiously mulls relaxing zero-COVID rules: analysts

There are signs that China is mulling less draconian public health controls amid ongoing protests in the streets and on university campuses, political analysts say. The Chinese government released a package of 20 new policy measures on Nov. 11 aimed at “optimizing” the country’s pandemic response, including slightly relaxed quarantine requirements for people returning home from areas designated “high risk.” The move has generally been seen as a cautious relaxation of the zero-COVID policy, espoused by Communist Party leader Xi Jinping as the only way forward when it comes to containing the virus, and comes amid growing public dissatisfaction with the policy and widespread censorship of dissenting voices. University students in the central city of Zhengzhou protested over long-running restrictions on Nov. 16, according to video clips uploaded to social media sites. One video clip showed masked young people in a heated discussion with an official in a black jacket, urging him to read the students’ demands, a copy of which was also circulating on social media. In a second clip, the Zhengzhou University students start shouting at the official in frustration after he appears to stall. “Looks like you’re not going to address a single one of these issues for us here tonight,” says one protester. Social media posts said the university’s Communist Party secretary came out to talk with students, but a live stream of the conversation was later blocked and student dorms searched by security officials. Protests in Guangzhou, Urumqi and Lhasa The students’ resistance to nationwide campus lockdowns followed street protests by migrant workers who broke out of lockdown in the southern city of Guangzhou, as well as protests in Urumqi and Ghulja in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, and the Tibetan capital Lhasa in recent weeks. Reports have emerged that the northern city of Shijiazhuang could be a pilot zone for a slightly more relaxed approach to mass testing. The Financial Times reported on Nov. 15 that the city is “tiptoeing away from Beijing’s most draconian pandemic measures, in what some see as a test case for a gradual retreat from President Xi Jinping’s strict zero-Covid policy.” People line up to be tested for COVID-19 on Flower City Square in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, China, Nov. 16, 2022. Credit: cnsphoto via Reuters Widespread rumors that the city is gearing up to “live with COVID-19” prompted the city’s party Secretary Zhang Chaochao to deny the move on Nov. 14, promising that the municipal authorities wouldn’t “lie flat” in the face of the threat from the virus. Former Chinese Red Cross Director Ren Ruihong said the government is announcing looser restrictions from Beijing, but leaving it to local officials to decide how best to control the virus locally — an issue that figures highly in government key performance indicators and therefore affects individuals’ career prospects. “The central government will gradually relax its pandemic prevention guidance, even if only to deflect public dissatisfaction from itself,” Ren told Radio Free Asia. “The situation with regard to different opinions [about how to implement the measures on the ground] is pretty chaotic right now, with the central government unwilling to take the blame.” This has left room for variation in local pandemic prevention policies, and caused a “disconnect” from Beijing, Ren said. This has resulted in an ongoing and severe lockdown in the southwestern megacity of Chongqing, while requirements for testing in Shijiazhuang have at least partly been dropped, according to a resident there who spoke to RFA. Still need negative PCR tests People returning to the city from low-risk areas still need a negative PCR test from the past 48 hours, and need the permission of their residential committees to return home. The same requirements apply to anyone leaving the city. While confusion remains over whether kindergarteners still need a recent negative test to attend school, resident Sun Liang said regular testing regardless of a person’s movements has been dropped, while “active testing” is still in place for travel to certain public places. “You still need a negative PCR from the past 24 hours to get into an office building, and a negative result from the past 48 or 72 hours to ride the subway or the bus,” Sun told RFA. Some districts appeared to be just as confused as residents by what was happening in their city, shutting down test stations only to reopen them a day later, according to social media posts. But Sun said the city is likely being used as a guinea pig for the rest of China. “It is indeed being used as a pilot, but it’s just not being totally freed from restrictions as some people have been saying,” he said. “If they totally removed all restrictions, then there might be a backlash in which people think the government doesn’t care what happens to them.” “A lot of pharmacies are now selling drugs you can take orally for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19, which may be an even bigger sort of pilot,” he said. The Financial Times cited several residents of Shijiazhuang as saying that the idea of loosening restrictions made them fearful of catching the virus. Veteran U.S.-based rights activist and political commentator Yang Jianli likened China’s COVID-19 policy to “riding a tiger.” “This is caused by the fact that Xi Jinping and the Chinese government failed to import internationally made vaccines in time in the wake of the Wuhan lockdown,” Yang said. “The Chinese government is in a dilemma right now. They are damned if they do, and damned if they don’t.” Translated and written by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.