The Hong Kong handover, or the transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom to the People’s Republic of China, took place at midnight on 1 July 1997. It ended 156 years of British colonial rule and was supposed to guarantee Hong Kong 50 years of autonomy under the framework of “one country, two systems.”

But what was promised and what has unfolded are starkly different. While Hong Kong was designated a Special Administrative Region (SAR), Beijing has steadily eroded the freedoms and rights it pledged to protect. From tightening political control and restricting free expression to imposing sweeping national security laws, China’s handling of Hong Kong has drawn widespread international criticism for dismantling the city’s autonomy far ahead of 2047.

On the occasion of China’s National Day, IJ-Reportika presents this report examining how Beijing has dealt with Hong Kong since the handover — beginning with a timeline of major events that reveal the steady march from promised freedoms to increasing authoritarian control.

May 24, 1998

First multi-party vote. The democratic party sweeps elections.

June 26, 1999

China's parliament overturns Hong Kong's highest court on right-of-abode provisions in the Basic Law, sparking a constitutional crisis over judicial independence.

September 11, 2000

Second legislative elections: Democratic Party returns as single largest group.

February, 2001

Deputy Chief Executive Anson Chan, a former deputy to Chris Patten and the main figure in the Hong Kong administration to oppose Chinese interference, resigns under pressure from Beijing and is replaced by Donald Tsang.

May 8, 2001

Chinese President Jiang Zemin's speech at the Global Fortune Forum disrupted by Falun Gong and democracy protesters.

June, 2002

Trial of 16 members of the Falun Gong arrested during a protest outside Beijing's liaison office. Falun Gong remains legal in Hong Kong, despite having been banned in mainland China in 1999, and the trial is seen as a test of the freedoms Beijing guaranteed to respect after the handover. The 16 are found guilty of causing a public obstruction.

September, 2002

Tung Chee-hwa's administration releases proposals for controversial new anti-subversion law known as Article 23.

July 1, 2003

Over 500,000 people march against Article 23. Two ministers later resign and the bill is indefinitely shelved.

April, 2004

China rules that its approval must be sought for any changes to Hong Kong's election laws, giving Beijing the right to veto any moves towards more democracy. It was done to deny direct elections for the chief executive in 2007 and the Legislative Council in 2008.

July, 2004

Some 200,000 people mark the seventh anniversary of Hong Kong's handover to Chinese rule by taking part in a demonstration protesting Beijing's ruling against electing the next chief executive by universal suffrage. The headline theme was "Striving For Universal Suffrage in '07 & '08 for the chief executive and Legislature respectively (爭取07, 08普選)."

September, 2004

Pro-Beijing parties retain their majority in LegCo elections widely seen as a referendum on Hong Kong's aspirations for greater democracy. In the run-up to the poll, human rights groups accuse Beijing of creating a "climate of fear" aimed at skewing the result.

June, 2005

Tens of thousands of people commemorate sixteenth anniversary of crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square.

July and December, 2005

Following the 2004 protest, the next major event was Tung Chee-hwa's resignation in March 2005. Two protests were held in 2005 including the annual 1 July event and a separate December 2005 protest for democracy. The theme for the march was "Oppose government collusion, striving for universal suffrage (反對官商勾結,爭取全面普選)".

January, 2007

New rules aim to restrict the number of pregnant women from mainland China who come to Hong Kong to give birth. Many had been drawn by the prospect of gaining Hong Kong residency rights for their children and evading China's one-child policy

July, 2007

Hong Kong marks 10th anniversary of handover to China. New government under Chief Executive Donald Tsang is sworn in. Plans for full democracy unveiled.

December, 2007

Beijing says it will allow the people of Hong Kong to directly elect their own leader in 2017 and their legislators by 2020. Mr Tsang hails this as "a timetable for obtaining universal suffrage", but pro-democracy campaigners express disappointment at the protracted timescale.

May 31, 2009

An estimated 200,000 attend a candlelight vigil on June 4 in memory of students who lost their lives during the Tiananmen Square Massacre. It's the largest turnout in 20 years. Hong Kong remains the only place in China to openly mark Tiananmen's anniversary.

June, 2014

More than 90% of the nearly 800,000 people taking part in an unofficial referendum vote in favour of giving the public a say in short-listing candidates for future elections of the territory's chief executive. Beijing condemns the vote as illegal.

Pro-democracy Protests in Hong Kong

July, 2014

Tens of thousands of protesters take part in what organizers say could be Hong Kong's largest pro-democracy rally in a decade.

August, 2014

Chinese government rules out a fully democratic election for Hong Kong leader in 2017, saying that only candidates approved by Beijing will be allowed to run.

August-September, 2014

The Umbrella Revolution Its name arose from the use of umbrellas as a tool for passive resistance to the Hong Kong Police's use of pepper spray to disperse the crowd during a 79-day occupation of the city demanding more transparent elections, which was sparked by the decision of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of the PRC (NPCSC) of 31 August 2014 that prescribed a selective pre-screening of candidates for the 2017 election of Hong Kong's chief executive.

September-November, 2014

Pro-democracy demonstrators occupy the city centre for weeks in protest at the Chinese government's decision to limit voters' choices in the 2017 Hong Kong leadership election. More than 100,000 people took to the streets at the height of the Occupy Central protests.

November, 2016

Thousands of people gather in central Hong Kong to show their support for China's intervention in the territory's political affairs after Beijing moves to have two pro-independence legislators removed from office.

November, 2016

The high court disqualifies pro-independence legislators Sixtus Leung and Yau Wai-Ching from taking their seats in the Legislative Council after they refused to pledge allegiance to China during a swearing in ceremony.

March, 2017

CY Leung's deputy Carrie Lam wins the Electoral College to become the next chief executive.

June, 2017

Chinese President Xi Jinping visits Hong Kong to swear in Chief Executive Carrie Lam, and uses his visit to warn against any attempt to undermine China's influence over the special administrative region.

June-July, 2019

Hong Kong sees anti-government and pro-democracy protests, involving violent clashes with police, against a proposal to allow extradition to mainland China.

National Security Law

China’s introduction of the wide-ranging National Security Law (NSL) for Hong Kong marked the most direct assault on the city’s autonomy since the 1997 handover. Pushed through in 2020, the law effectively dismantled the “one country, two systems” promise, stripping away the freedoms and protections that Beijing had pledged to uphold for 50 years.

The 66 articles of the law were kept secret until after its passage, denying public debate or legislative scrutiny. Once enacted, it criminalized vaguely defined acts of:

- Secession – advocating separation from China

- Subversion – challenging the power of Beijing

- Terrorism – using violence or intimidation

- Collusion with foreign forces – engaging with international actors in ways China disapproves

Under these sweeping and ambiguous categories, authorities gained broad powers to silence dissent, prosecute protesters, and dismantle civil society. The NSL has been widely condemned as the measure that ended Hong Kong’s autonomy and freedoms, turning the city into another territory under Beijing’s authoritarian grip.

Changes in Hong Kong after the National Security Law

Changes in Hong Kong After the National Security Law

Hong Kong changed irrevocably after the forceful imposition of the National Security Law (NSL) in 2020. Instead of safeguarding autonomy as promised under “one country, two systems,” the law tightened Beijing’s grip and reshaped every aspect of Hong Kong’s political and civic life.

One of the most visible impacts has been on media freedom and public trust. According to the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI), public satisfaction with the performance of news media has plunged to its lowest point since records began in 1993. This collapse reflects not only growing censorship but also the erosion of press independence.

Journalists faced unprecedented repression: many were arrested, threatened, or harassed into silence. Some were forced to abandon the profession altogether for standing against the unjust law. The ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) launched a sweeping crackdown on pro-democracy voices in the media, politics, and civil society.

This campaign resulted in the forcible closure of major outlets such as Jimmy Lai’s Next Digital, including the iconic pro-democracy Apple Daily newspaper. Independent platforms like Stand News, FactWire, and Citizen News were also shut down. Even established broadcasters like iCable and RTHK underwent “rectification” — a euphemism for being reshaped into tools aligned with Beijing’s official narrative.

The NSL did not just restrict freedoms; it systematically dismantled the foundations of a free press and open society, marking the end of Hong Kong’s autonomy and its reputation as a bastion of liberty in Asia.

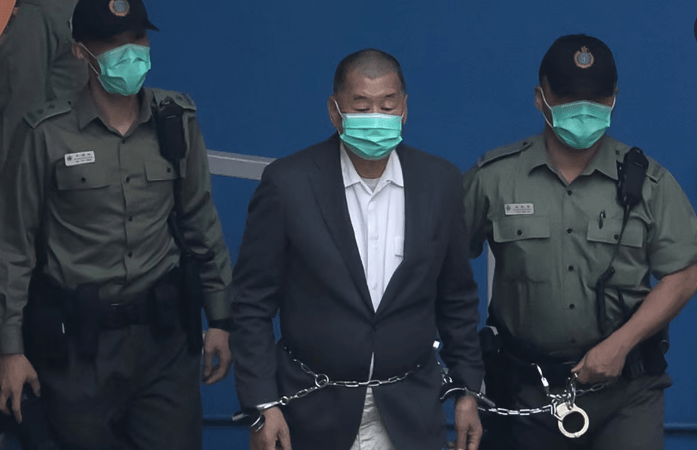

- Jimmy Lai : Hong Kong media mogul Jimmy Lai has been sentenced to 13 months in jail for participating in a vigil marking the 1989 Tiananmen massacre in Beijing.

- Allan Au : A veteran reporter and journalism lecturer, was arrested in a dawn raid by Hong Kong’s national security police.

- Stand News : Hundreds of Hong Kong national security police raided the office of online pro-democracy media outlet Stand News and arrested six people, including senior staff, for “conspiracy to publish seditious publications.”

Even under the shadow of the National Security Law, the spirit of Hong Kong’s independent press has not been completely extinguished. In the year following the closure of Apple Daily, some of its former reporters continued publishing stories through social media, determined to keep the pro-democracy voice alive. However, as Beijing’s crackdown deepened, many of these efforts have been forced into silence. Several journalists remain detained or on trial, while others have gone into exile or left the profession under threat of prosecution. Public trust in the media has collapsed to historic lows, and once-vibrant outlets like Stand News and Citizen News have been shut down. Yet, the perseverance of a handful of independent reporters — still finding ways to write, publish, and resist — serves as a reminder that despite Beijing’s efforts to erase it, the spirit of press freedom in Hong Kong endures, however fragile.

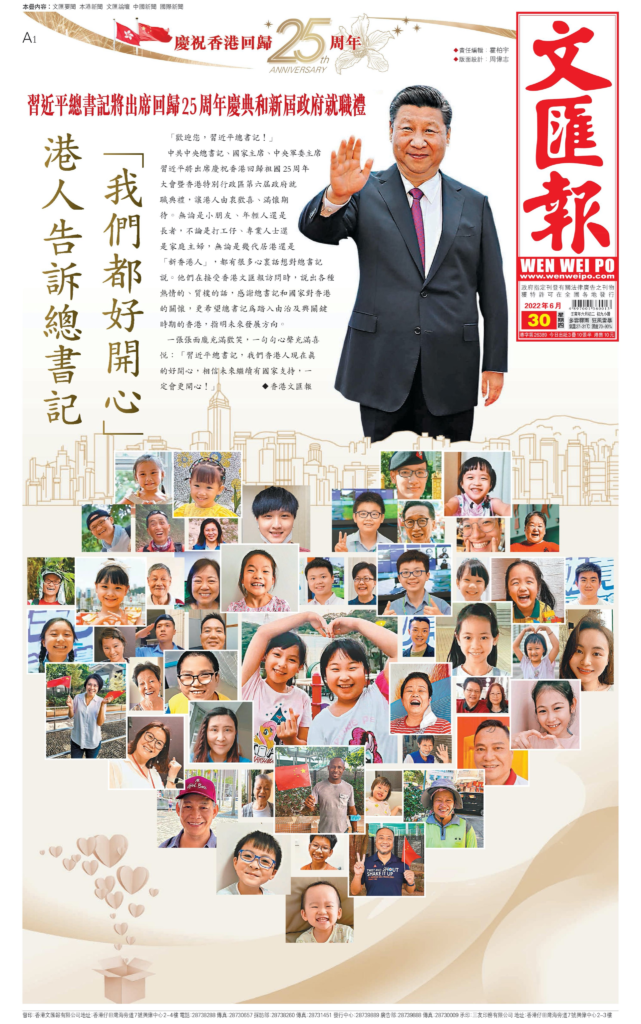

But the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) continues to do what it does best — silence and censor critical voices in Hong Kong. In a stark illustration of Beijing’s tightening grip, the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) reported that at least ten local and international media organizations — including Reuters, Bloomberg News, AFP, and even the South China Morning Post — were barred from covering the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover from the United Kingdom to China. This deliberate exclusion of respected global outlets underscored the CCP’s determination to control the narrative, deny transparency, and prevent the world from witnessing the reality of Hong Kong under authoritarian rule.

At the same time, pro-China media in Hong Kong flooded the airwaves and print pages with praise for Xi Jinping, carefully choreographed to project unity and celebration. Every face was shown as “full of laughter,” every sentence scripted to express joy: “General Secretary Xi Jinping, we Hong Kongers are so happy.” This manufactured adulation stood in stark contrast to the silenced dissent, shuttered newsrooms, and jailed journalists. It revealed not genuine joy, but the depth of Beijing’s propaganda machine, which now dominates Hong Kong’s media landscape by replacing independent reporting with orchestrated loyalty to the CCP.

The CCP has also moved aggressively into education, reshaping how young Hongkongers understand their identity and history. Core subjects such as History, Chinese History, Life & Society, and Economics have been rewritten to align with Beijing’s narrative. According to experts, the revised curriculum is designed not to foster critical thinking but to ensure that students “appreciate” Chinese culture and history, while systematically undermining Hong Kong’s distinct culture, heritage, and democratic values. By controlling what future generations learn, the CCP is attempting to erase Hong Kong’s unique identity and replace it with unquestioning loyalty to the mainland.

The CCP changed the content of subjects like History, Chinese History, Life & Society, and Economics. According to the experts on China’s growth in the region, students will appreciate Chinese culture and history and undermine the culture and history of Hong Kong after studying the updated textbooks.

What Colonialism does is create an identity crisis about one’s own culture

Lupita Nyong’O

Education Under the National Security Agenda

One of the CCP’s most far-reaching strategies to consolidate control over Hong Kong has been the rewriting of education. Curriculum reforms have been introduced across key subjects — Chinese History, History, Life & Society, and Economics — embedding “national security education” at both junior and senior high levels.

In Chinese History, junior high students are now required to “comprehensively understand” events and personalities in Chinese history through the lens of political and cultural security, emphasizing loyalty, national identity, and responsibility. Lessons stress how the Chinese nation “overcame foreign invasions,” including the “British occupation of Hong Kong,” framing the handover as China’s heroic recovery of sovereignty. At the senior high level, the narrative deepens: compulsory topics like the anti-Japanese war, foreign invasions, and the open-door policy are taught with the goal of building “a full and comprehensive sense of the nation” and instilling appreciation for “traditional culture” as the foundation for political stability and ethnic unity.

The History subject mirrors this agenda. At the junior high level, it pushes students to accept that “Hong Kong from ancient times has been a part of Chinese territory” and that China’s sovereignty was “rightfully restored” after British rule. Senior high history places even greater weight on political and cultural security, conditioning students to see themselves primarily as “responsible Chinese citizens with a global vision.”

The subject of Life and Society now requires students to study China’s constitution alongside the Basic Law, presenting them as inseparable. This forces students to recognize Beijing’s primacy over Hong Kong’s governance, while drilling into them the concepts of national, political, military, and economic security — even the safeguarding of China’s overseas interests.

In Economics, senior high students are taught not just about money, trade, and finance, but also about the duty of Hong Kong to maintain China’s economic security, while Beijing is portrayed as the guarantor of Hong Kong’s prosperity.

These sweeping changes are accompanied by a purge of dissent from schools and universities. Since 2020, more than 6,400 teachers have left the city’s public schools, while 600 university professors and staff have also exited, according to the Education Bureau. Libraries have removed hundreds of books referencing the 2019 protests or the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. Works such as the autobiography of Wang Lingyun, mother of student leader Wang Dan, and writings by ousted premier Zhao Ziyang have been erased from circulation. Wang described the removal as clear evidence of Hong Kong’s suffocating loss of freedom of expression.

Perhaps the most telling example of this distortion came in new history textbooks that astonishingly claim Hong Kong “never was a British colony.” This revisionist narrative epitomizes Beijing’s efforts to rewrite the past, control the present, and shape the minds of Hong Kong’s future generations.

Exodus of Educators: Voices Silenced Under Pressure

Many teachers and media personnel have left Hong Kong and many are planning to leave amid FEAR and INSECURITY.

A visual arts teacher “vawongsir“ who was deregistered last April over posting pro-democracy political cartoons on social media has left Hong Kong. He cited pressure from the city’s Education Bureau and criticism from Beijing-backed media. He made the following post before leaving the city.

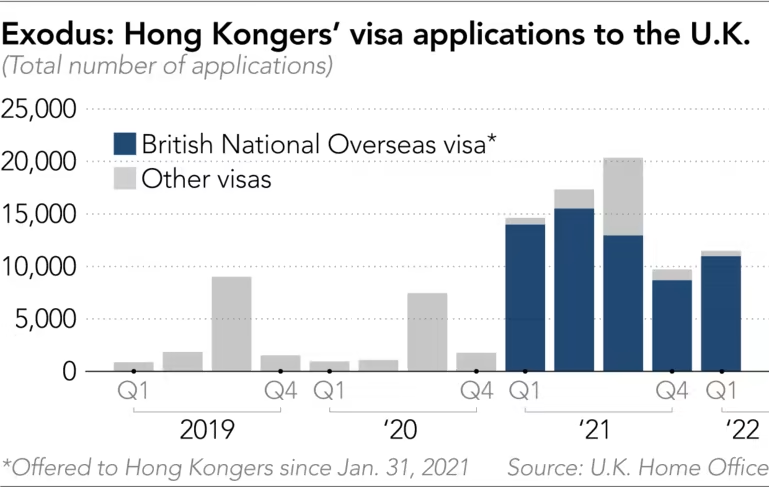

People are leaving Hong Kong and going to countries like UK. Can it be called EXODUS?

A film censorship law that passed last year has cemented the CCP’s oversight of any creativity, sparking an exodus of filmmakers, including Ngan Chi-sing (also known as “Twinkle”), director of “Love in the Time of Revolution,” an ode to the 2019 protests. Ngan was forced to relocate to the United Kingdom.

A State in the grip of neo-colonialism is not master of its own destiny. It is this factor which makes neo-colonialism such a serious threat to world peace.

Kwame Nkrumah (1965). “Neo-colonialism: the last stage of imperialism”, Nelson

Conclusion

The trajectory of Hong Kong since the enactment of the National Security Law reflects an unrelenting clampdown on freedoms once guaranteed under the “one country, two systems” framework. With thousands arrested, educators and journalists forced into silence or exile, and classrooms reshaped to promote Beijing’s narratives, the city’s identity is undergoing a forced transformation. Fear and insecurity now dominate public life, as civil society continues to shrink under political pressure. While pro-China media hails Xi Jinping as a figure of stability, the reality on the ground is one of dwindling freedoms, mounting self-censorship, and a population grappling with the loss of its once-vibrant democratic space.