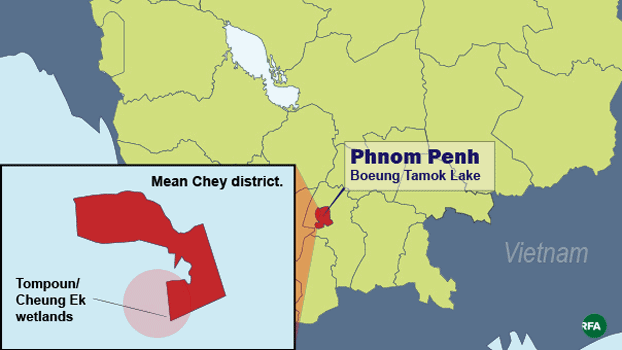

Cambodian’s autocratic Prime Minister Hun Sen has doled out at least 900 hectares of land reclaimed from one of the last large natural lakes in Phnom Penh to his sister, a wealthy tycoon and ally, and top military officials all benefiting from the largesse, according to a domestic land rights organization. The privatization and filling of Boeung Tamok Lake, also known as Beoung Tumnup Kabsrov, has picked up during the past few years, with little left of the body of water on the northwest side of the capital city. The lake spans six communes in Prek Pnov and Sen Sok districts and is home to a diverse ecosystem of birds and fish. It is also home to 300 families and 1,000 people, many of whom earn a living through fishing, aquaculture farming and home-based businesses, according to the Cambodian NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT). Most of the families live in dilapidated and poorly built housing, with 30% residing in makeshift shelters. The lake’s boundaries were officially demarcated in 2016 when the Cambodian government declared Boeung Tamok’s original 3,240 hectares as state public property, according to an April 2021 report by the NGO. As part of a land privatization drive, the government granted dried-out parts of the lake to ministries authorized to resell the land for urban development projects and to oligarchs and cronies close to the government, STT reported. In more than four years, the government has issued more than 40 directives to reclaim parts of the lake or to give away the land, according to STT, which assists poor communities to protect their rights to land and housing. As of late 2021, the government had reclaimed more than half of the lake area, or about 1,670 hectares. Hun Sen-approved land giveaways that went to 11 government ministries and institutions, including the Interior, Justice and Health ministries, Phnom Penh City Hall and the National Police, according to STT and to reports by VOD, a local independent media outlet. The Ministry of Interior, for instance, sold the allocated land to finance the construction of a new building headquarters on the old site. In addition, 22 individuals also received reclaimed lake land from Hun Sen. Among those who have benefited are his sister, Hun Seng Ny, who received 20 hectares of land. Vong Pisen, commander-in-chief of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces; Sao Sokha, deputy commander-in-chief of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces; and other senior military officers each received more than 36 hectares, VOD reported based on information in subdecrees signed by Hun Sen. Kok An, a wealthy tycoon close to the prime minister, received 155 hectares of land. Hun Sen also handed over 100 hectares to Chheng Thean Seng, the younger sister of wealthy real estate businesswoman Chheng Sopheap, also known as Yeay Phu, who has been implicated in several land grab scandals in Cambodia. Say Sophea, wife of Phoeung Phalla, a two-star general of the Special Forces Parachute Unit, received 75 hectares, VOD reported Environmental activist Thon Ratha, who was jailed for criticizing the government’s reclamation of Boeung Tamok, said he fears that the lake could soon disappear, like other natural lakes in Boeung Tumpun and Boeung Choeung Ek districts. The fact that individuals close to Hun Sen received parcels of the restored land raises a suspicion of corruption, he said. “Whether to sell or rent, how much to sell for, or whether to rent it and for how long — we seem to have no information about these questions other than the decision to give parts of the lake to this person and that person,” he told RFA. “That’s why I’m still skeptical. We’re worried that there may be a systematic conspiracy or corruption.” A map shows Phnom Penh’s Boeung Tamok Lake and the Tompoun/Cheung Ek Wetlands. Credit: RFA graphic ‘It belongs to the state’ Government spokesman Phay Siphan said that those who acquired land bought it from the original owners. He also said that before the government offered the land for sale, state institutions assessed the impact on local communities living there, though he did not know if the reclamations had forced some residents to leave their homes. “They bought it from the people in two stages, during which they asked for a [subdecree] to cut away part of the land from the lake,” he said. Seang Muy Lai, director of the Housing Rights and Research Project at Sahmakum Teang Tnaut, said that Boeung Tamok should be kept for the benefit of the public. More than 200 poor families living on the lake face eviction, Seang Muy Lai said. “It is unreasonable to give away parts of the lake that are two to three meters deep,” he said. “There should be no one occupying it. It is illegal to allow anyone to occupy the lake because it belongs to the state.” The environmental watchdog group Mother Nature Cambodia has urged the government to stop the development of reclaimed areas of the lake because of the negative impact on communities that rely on the body of water for their livelihoods and significant flooding in the city as the result of runoff during heavy rains. Lim Kean Hor, Cambodia’s minister of water resources and meteorology, has clashed with Hun Sen over the issue for expressing growing concern over the encroachment on the riverbanks and waterways that are properties of the state and has warned that warned that flooding is connected to landfilling developments such as Boeung Tamok. “The bank of the river, the river, the creek, the canal, and the lake, these are all public properties, so all provincial authorities and governors must take measures to facilitate the prevention of abuse from dumping land which is not in compliance with the law,” he said in a May 2020 letter issued all municipal governments and provincial authorities. Reported by RFA’s Khmer Service. Translated by Sok Ry Sum. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.