An investigation into the world’s leading ranking reports

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

Global ranking reports such as the World Press Freedom Index, Corruption Perceptions Index, and World Happiness Report have become benchmarks for assessing nations on critical issues. Governments, policymakers, and international organizations often use these rankings to guide decisions, shape perceptions, and influence geopolitical strategies. Media outlets amplify their findings, while opposition parties leverage them to criticize ruling governments. Yet, despite their widespread importance, these reports are not beyond scrutiny.

Investigative Journalism Reportika uncovers the startling reality behind these globally celebrated indices: they are often riddled with inaccuracies, methodological flaws, data limitations and in some cases, blatant propaganda. While these reports claim to offer unbiased assessments, they sometimes perpetuate biases, create misleading narratives, or fail to account for the cultural and regional complexities they aim to measure.

This investigative series delves deep into the reliability of these reports. In this first instalment of this report, we focus on several widely referenced indices, exposing severe issues. From unexpected discrepancies to controversies surrounding their credibility, we examine the gaps that question their validity. In Part Two, we will explore additional reports, continuing to unravel their systemic flaws.

This report is the result of months of meticulous investigation by the experts at Investigative Journalism Reportika. Drawing from on-the-ground studies, in-depth data reviews, and insights from leading economists, geopolitical analysts, and seasoned researchers, our team has dissected the inner workings of these reports to reveal their shortcomings. Each finding is backed by rigorous analysis, contextual understanding, and a commitment to uncovering the truth beyond the numbers.

What’s Wrong with the World Press Freedom Index ?

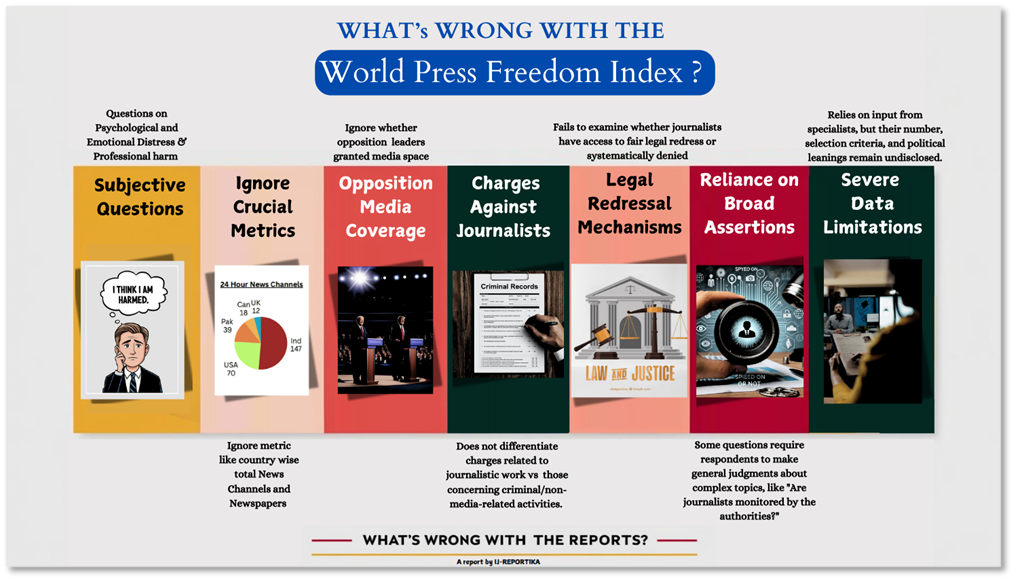

The investigation by Investigative Journalism Reportika into the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) has revealed several key issues with its methodology that raise concerns about its accuracy. While the Index aims to rank countries based on press freedom, its reliance on subjective perceptions from experts and journalists introduces significant bias. Issues such as the emotional distress faced by journalists, vague survey questions, and the failure to distinguish between government-controlled and independent media have led to inconsistencies in the rankings. Furthermore, the Index does not account for the diverse media landscapes and regional differences, resulting in an incomplete and sometimes misleading assessment.

The investigation also highlights how the World Press Freedom Index overlooks crucial factors that shape press freedom globally. Countries with diverse and vibrant media environments, like India and Singapore, are often misrepresented, while political biases in the rankings have led to criticism from governments worldwide. As the investigation delves deeper into these discrepancies, it calls for a more transparent, data-driven approach to better reflect the complexities of press freedom across different regions.

To learn more about these findings, read the full report: What’s Wrong with the World Press Freedom Index

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

What’s Wrong with the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI)?

The investigation by Investigative Journalism Reportika into the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) reveals significant flaws in its methodology, which undermine its reliability and fairness. The CPI, compiled by Transparency International, ranks countries based on perceived corruption, but its reliance on expert assessments and business leader opinions leads to subjective scores influenced by media narratives and individual biases. For instance, countries with limited media freedom, like China, may receive lower corruption scores, while those with freer presses may score higher despite ongoing corruption issues.

Key concerns include inconsistencies in data sources, particularly in countries with limited data availability, and the CPI’s failure to capture corruption in the private sector or within organized crime networks. The index also oversimplifies complex corruption dynamics by standardizing scores across diverse nations with unique governance and corruption challenges. Additionally, Transparency International’s lack of transparency in how private data sources are used adds to the lack of trust in the results.

You can read the full investigation report on the flaws in the Corruption Perceptions Index : What’s Wrong with the Corruption Perceptions Index?

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

What’s Wrong with the World Happiness Report ?

The World Happiness Report, published annually since 2012, has become a key reference point for understanding global well-being, ranking countries based on the self-reported happiness of their citizens. Created as part of a United Nations initiative, the report shifts the focus from traditional economic measures to indicators of life satisfaction, drawing from data provided by the Gallup World Poll. It links happiness to factors such as income, social support, life expectancy, and perceptions of corruption, positioning it as an influential tool for policymakers seeking to foster societal well-being.

However, this report is not without its controversies and significant methodological flaws. As part of this investigative report by Investigative Journalism Reportika, we critically examine the weaknesses inherent in the World Happiness Report’s data collection and analysis processes. Issues such as the subjectivity of life evaluations, reliance on proxy measures for missing data, and inconsistent data coverage across nations call into question the reliability of its findings. Moreover, the Gallup survey’s sampling methodology, which often overlooks marginalized groups and rural populations, further undermines the representativeness of the report. These flaws raise crucial concerns about the validity of the rankings and their implications for global policy decisions.

Explore the full report to uncover the hidden factors shaping global happiness rankings: What’s Wrong with the World Happiness Report?

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

What’s Wrong with the USCIRF Annual Reports ?

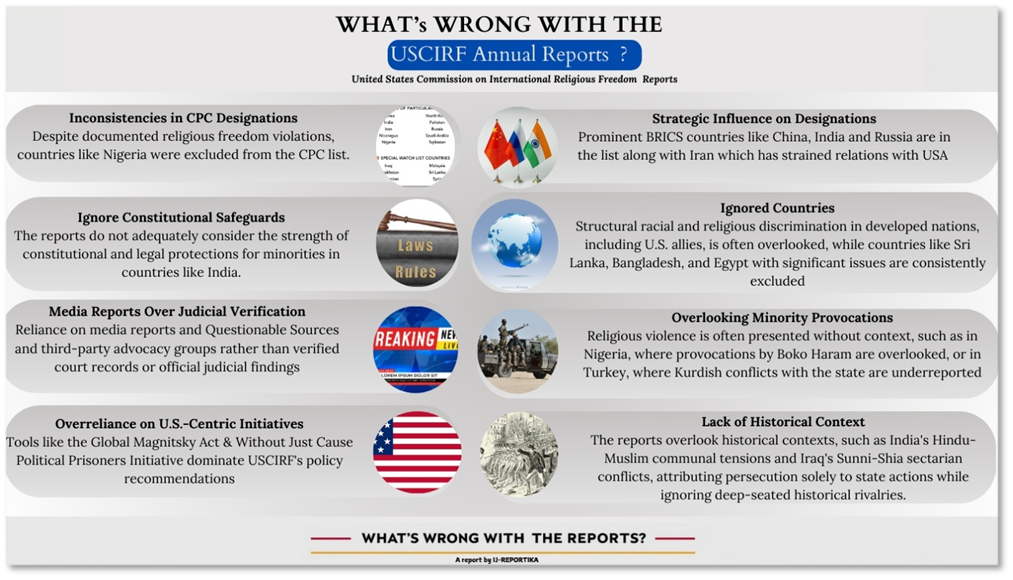

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) Annual Reports, while central to global advocacy for religious freedom, suffer from methodological inconsistencies, selective reporting, and geopolitical biases. Countries like China, Iran, and Russia, often adversarial to U.S. interests, dominate the “Countries of Particular Concern” (CPC) list, while nations like Nigeria, despite documented violations, are overlooked. This selective focus undermines the credibility of the reports, suggesting that political strategy outweighs objective criteria. Additionally, structural racism and ethnoreligious discrimination in Western nations and U.S. allies are often ignored, further reflecting a skewed narrative.

The reports rely heavily on media accounts and NGO submissions, often lacking judicial or independent verification, which compromises their accuracy. Small, unrepresentative datasets and the omission of socio-economic contexts, such as minority population growth or educational initiatives, weaken the reports’ comprehensiveness. By selectively addressing violations and ignoring broader structural issues, USCIRF risks perpetuating a narrative that aligns with U.S. strategic interests rather than serving as a balanced, global standard for religious freedom advocacy.

Read the complete report to explore these critical insights: What’s Wrong with the USCIRF ANNUAL REPORTS?

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

What’s Wrong with the Global Hunger Index ?

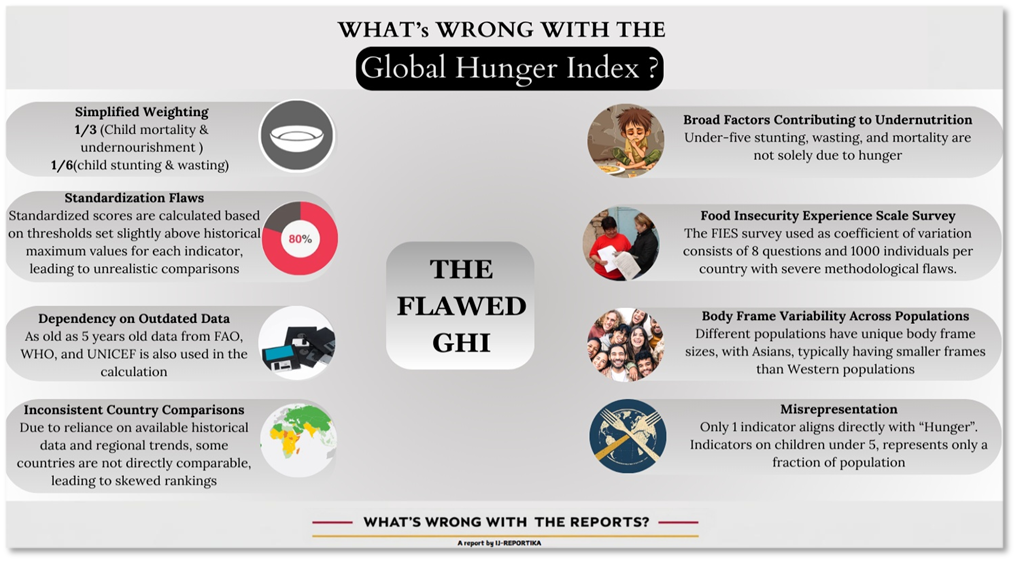

This investigative report by Investigative Journalism Reportika reveals critical methodological flaws in the Global Hunger Index (GHI), highlighting inaccuracies in how hunger is measured and ranked globally. The report identifies the uneven weighting of indicators—undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting, and child mortality—which oversimplifies the multifaceted nature of hunger. Additionally, stunting and mortality, which reflect broader health and nutrition issues, are mischaracterized as direct measures of hunger. The index’s narrow focus on children under five excludes significant portions of the population, distorting the overall representation of hunger. Furthermore, reliance on outdated data, regional trends, and oversimplified metrics undermines the index’s capacity to provide accurate, real-time comparisons across countries.

The report also uncovers unexpected ranking discrepancies that fail to align with ground realities. For instance, Vietnam, with significant agricultural advancements, is ranked higher than Tanzania, while countries like India and Indonesia, with robust food security programs, rank lower than nations with fewer resources and less infrastructure. Additionally, systemic biases, including double-counting of undernourishment data and overlooking structural factors like governance, conflict, and economic capacity, further weaken the GHI’s reliability. By addressing these methodological gaps and adopting a more comprehensive and transparent approach, the GHI could become a more effective tool for tackling global hunger.

Discover the full story and uncover the deeper issues with FIES Survey in the report: What’s Wrong with the Global Hunger Index ?

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

Conclusion

In conclusion, global indices such as the World Press Freedom Index, Corruption Perceptions Index, and others wield significant influence in shaping international narratives, government policies, and public perceptions of nations. These indices often act as benchmarks, not only for assessing performance but also for influencing geopolitical alliances, public opinion, and domestic political debates. Their rankings are frequently cited by governments, opposition groups, media outlets, and international organizations, lending them an air of authority and credibility. However, as this report demonstrates, the accuracy and objectivity of these indices are far from assured.

Through a comprehensive investigation, Investigative Journalism Reportika has revealed the deep-rooted methodological flaws, inherent biases, and data limitations that plague these indices. By relying heavily on qualitative inputs from a select group of specialists—whose selection criteria, affiliations, and political ideologies remain undisclosed—these rankings often fail to provide an impartial and transparent assessment. Furthermore, the over-reliance on subjective perceptions, coupled with a lack of consistency in data collection methods, undermines their credibility. In many cases, these indices appear to serve not as neutral tools but as mechanisms for shaping narratives that align with particular agendas or ideologies.

The findings in this report underscore the urgent need to critically evaluate these indices, especially given their outsized impact on global discourse. Policymakers, scholars, and media professionals must question their methodologies, demand greater transparency, and resist the temptation to treat these rankings as definitive truths. Blind reliance on flawed data risks perpetuating misconceptions and amplifying biases that have far-reaching consequences for governance, international relations, and public trust.

As part of its commitment to truth and accountability, Investigative Journalism Reportika will continue to delve into these issues in the second part of this report. By analyzing additional indices and their methodologies, we aim to further expose the ways in which these tools can mislead, oversimplify, and, at times, manipulate. The ultimate goal is to foster a more informed global conversation—one that prioritizes accuracy, fairness, and integrity over convenience or ideology.