High stakes, low expectations as top US diplomat opens China visit

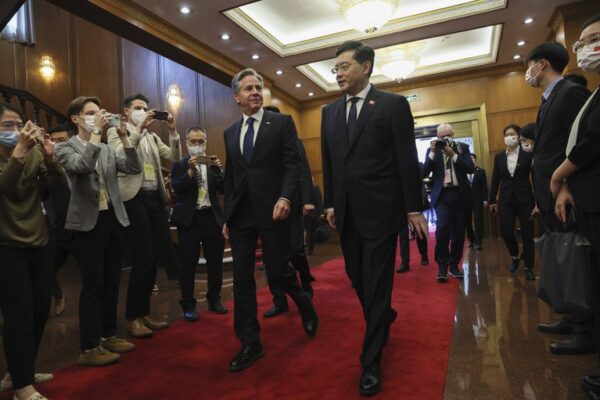

UPDATED AT 02:00 pm EDT on 2023-06-18 U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken opened a high-stakes visit to China on Sunday with lengthy talks with top Chinese officials that both countries described as “candid” and “constructive” and called for more stable ties after years of rising tensions. Blinken is the first secretary of state to visit China in five years, amid China’s strict coronavirus pandemic lockdowns and strains over the self-governing island of Taiwan, Russia’s war in Ukraine, Beijing’s human rights record, assertive Chinese military moves in the South China Sea and technology trade. The top U.S. diplomat began two days of meetings with extended talks with Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang and other officials and a working dinner at Diaoyutai State Guesthouse. Neither Blinken nor Qin made any substantive public comments during their meetings. Blinken’s talks with Qin were “candid, substantive, and constructive,” said State department spokesperson Matthew Miller. “The Secretary emphasized the importance of diplomacy and maintaining open channels of communication across the full range of issues to reduce the risk of misperception and miscalculation,” Miller said in written statement late Sunday. Blinken, the spokesperson added “raised a number of issues of concern, as well as opportunities to explore cooperation on shared transnational issues with the PRC where our interests align.” Chinese state media described the talks as “candid, in-depth and constructive communication on the overall relationship between China and the United States and related important issues.” The report quoted Qin as saying that “Sino-US relations are at the lowest point since the establishment of diplomatic relations. This does not conform to the fundamental interests of the two peoples, nor does it meet the common expectations of the international community.” “China is committed to building a stable, predictable and constructive Sino-US relationship,” the Chinese-language report quoted Qin as saying. “It is hoped that the U.S. side will uphold an objective and rational understanding of China, meet China halfway, maintain the political foundation of Sino-U.S. relations, and handle unexpected incidents calmly, professionally and rationally,” the Chinese foreign minister added. As he had in a blunt pre-meeting phone call with Blinken on Wednesday, however, Qin said China would not budge on its “core interests,” including that the self-governing island of Taiwan will be reunited with the mainland. Qin called Taiwan “the core of China’s core interests, the most important issue in Sino-US relations, and the most prominent risk,” Sunday’s readout said. Blinken is slated to have further talks with Qin, as well as China’s top diplomat Wang Yi, director of the Central Foreign Affairs Office, on Monday. Observers see a possible meeting with President Xi Jinping as a barometer of Beijing’s willingness to re-engage with Washington after years of frosty ties. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, center, left, walks with Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang, center right, at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing, China, Sunday, June 18, 2023. (Leah Millis/Pool Photo via AP) The visit comes after almost a year of strained relations between the Biden administration and Beijing, which began with then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s trip to Taiwan in August. Other irritants include China’s diplomatic and propaganda support for Russia for its war against Ukraine, and U.S. allegations that Beijing is attempting to boost its worldwide surveillance capabilities. Blinken postponed a planned February trip to China after a suspected Chinese spy balloon flew over U.S. airspace and was shot down. This visit went ahead despite the revelations early this month of a multibillion-dollar Chinese spy base in Cuba. He told reporters before leaving Friday that Washington wants to improve communications “precisely so that we can make sure we are communicating as clearly as possible to avoid possible misunderstandings and miscommunications.” ‘Legitimate differences’ President Joe Biden told White House reporters Saturday he was “hoping that over the next several months, I’ll be meeting with Xi again and talking about legitimate differences we have, but also how … to get along.” U.S. defense officials say Chinese officials have refused phone calls since Blinken canceled a planned trip to Beijing in February due to the Chinese spy balloon. Beijing asserts it was a weather balloon. Chinese Defense Minister Li Shangfu also declined to meet with U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore earlier at the start of the month, with Li instead using the forum to accuse the United States of “double standards.” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken (2nd R) and China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang (2nd L) meet at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing on June 18, 2023. Credit: Leah Millis / POOL / AFP There have been recent high-level contacts, including a trip to China by CIA chief William Burns in May, a visit to the U.S. by China’s commerce minister, and a meeting in Vienna Austria between Wang and Biden’s national security adviser Jake Sullivan. Reuters news agency quoted a senior State Department official as telling reporters during a refueling stop in Tokyo that Washington and Beijing understand they need to communicate more. “There’s a recognition on both sides that we do need to have senior-level channels of communication,” the official said. “That we are at an important point in the relationship where I think reducing the risk of miscalculation, or as our Chinese friends often say, stopping the downward spiral in the relationship, is something that’s important,” the official said. “Hope this meeting can help steer China-U.S. relations back to what the two Presidents agreed upon in Bali,” tweeted Chinese assistant foreign minister Hua Chunying. Biden and Xi met face-to-face on the sidelines of a summit of the Group of 20 big economies in November and agreed to try to restore dialogue despite sharp differences. The two leaders have opportunities to meet later this year, including at the Group of 20 leaders’ gathering in September in New Delhi and at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in November in San Francisco. Updated with statements from the U.S. and China after Sunday’s meetings.