Linghu Changbing will be 23 this year. Even before the pandemic hit China, he was already starting to feel that the traditional goals of marriage, a mortgage and kids were beyond his reach.

“I had no time to find a girlfriend back in China, because I was working from eight in the morning to 10 at night, sometimes even till 11.00 p.m. or midnight, with very little time off,” said Linghu, who joined the “run” movement of people leaving China in 2022.

“I didn’t earn very much, so I couldn’t really afford to go out and spend money having fun with friends, or stuff like that,” he says of his life before he left for the United States.

“I had very little social interaction, because I didn’t have any friends, which meant that I couldn’t really pursue a relationship,” he said. “As for an apartment, I had no desire to buy one at all.”

The situation he describes is common to many young people in China, yet not all are in a position to leave.

They are part of an emerging social phenomenon and social media buzzword: the “young refuseniks” – people who reject the traditional four-fold path to adulthood: finding a mate, marriage, mortgages and raising a family.

They are also known as the “People Who Say No to the Four Things.”

Three years of stringently enforced zero-COVID restrictions left China’s economic growth at its lowest level in nearly half a century, with record rates of unemployment among urban youth.

Refusing to pursue marriage, mortgages and kids emerged from that era as a form of silent protest, with more and more people taking this way out in recent years.

‘Far too high a price’

Several young people who responded to a brief survey by RFA Mandarin on Twitter admitted to being refuseniks.

“I’m a young refusenik: I won’t be looking for a partner or getting married, I won’t be buying a property and I don’t want kids,” reads one comment on social media.

“Finding love comes at far too high a price,” says another, while another user comments: “It’s all very well having values, or being sincere, but all of that has to be backed up with money.”

“It’s not that I’m lazy,” says another. “Even if I were to make the effort, I still wouldn’t see any result.”

Others say they no longer have the bandwidth to try to achieve such milestones.

“I’ve been forced back in on myself to the point where I feel pretty helpless,” comments one person.

For another, it’s more of a moral decision: “I think the best expression I can make of paternal love is not to bring children into this world in the first place.”

Similar comments have appeared across Chinese social media platforms lately, and have been widely liked and reposted.

Marriage rates have been falling in China for the past eight years, with marriages numbering less than eight million by 2021, the lowest point since records began 36 years ago, according to recent figures from the Civil Affairs Ministry.

People are also marrying much later, with more than half of newly contracted marriages among the over-30s, the figures show.

According to Linghu Changbing, who dropped out of high school at 14 and moved through a number of cities where he supported himself with various jobs, refuseniks are mostly found in the bigger cities with large migrant populations.

Young people in smaller cities like his hometown are more likely to be able to afford a home, and will often marry and start families as young as 18.

“In my experience, refuseniks seem to cluster mostly in the busier cities,” he says. “The more competitive a city, the more you will see this phenomenon.”

Curling up, lying flat, running away and venting

Shengya, a migrant worker in Beijing, has a similarly depressing view.

He spent two years doing nothing at his parents’ house, a phenomenon that has been dubbed “lying flat” on social media.

“I basically lay around at home the whole time,” he said. “I couldn’t get motivated to do anything. My dad asked me why I didn’t go out and get a job, and I told him: ‘The only point of a job would be to prevent starvation, but I already get enough to eat here, so what difference would it make?'”

Linghu Changbing went through a very similar phase, until someone got him a job working overseas.

Looking back on that time, he says that China’s young refuseniks are similar to the rats in the Universe 25 experiments by ethologist John B. Calhoun in the 1960s, in which rats given everything they needed eventually stopped bearing young, leading the population to collapse.

“The marginalized rats gradually gave up competing at all, and suppressed their natural desires, leading to constant personality distortions,” he says.

“Lying flat” has entered the online lexicon as a way of describing the passive approach adopted by many young people in China, while “curling up,” also known as “turning inwards,” describes a personality turned in on itself from a lack of external opportunity for change.

While those who can join the “run” movement, leaving China to seek better lives overseas, others act out their frustrations in indiscriminate attacks on others, known on social media as “giving it your all,” or “venting.”

For late millennials and Generation Z in China, curling up, lying flat and running away are the main available options, as not many young people have the wherewithal to leave the country and start a new life elsewhere.

‘A very heavy burden’

A Chengdu-based employee of an architectural firm, who gave only the nickname Mr. J, said he first came to the realization that he would be a refusenik during the rolling lockdowns, mass incarceration in quarantine camps and compulsory daily testing of the zero-COVID policy.

Mr. J says he won’t be buying a home.

“As the zero-COVID measures were stepped up in 2022, I kept seeing these stories online about the terrible situation of homeowners with mortgages,” he says. “Some of them were jumping off buildings or refusing to make mortgage payments.”

“Meanwhile, some of my friends who had bought properties because they thought residential housing prices would rise have been left with mortgages that have become a very heavy burden due to the sharp drop in their incomes in recent years,” he says.

He is also worried about his parents’ retirement, and knows that paying for his wedding and helping him buy an apartment would leave a huge hole in their much-needed savings.

“If I can’t help them to improve their lives, then the least I can do as their son is to lighten their burden,” he says.

But he is still very worried about his own future, given the current state of the Chinese economy. His monthly income of a few thousand yuan is only enough to cover his daily expenses, following years of stagnant wages and rising prices.

“It’s an indisputable fact that China’s economy is slowing down,” he says. “I can’t be sure that incomes will keep on rising, like they did back in the 1970s and 1980s, either.”

“So, not buying a house, not getting married, not having children, and spending less are the best options for me right now,” he says.

China’s refuseniks seem to come from a variety of social and economic backgrounds, and even include returnees from overseas study, who are typically more highly qualified and better off than most.

But the thing they have in common is that they chose this lifestyle due to huge competitive pressures in all areas of their lives.

“No room for me”

A Generation Z anthem by Chinese rockers New Pants titled “People with no ideals don’t get hurt” contains the repeated line: “No room for me.”

A viral video of a crowd of young people singing and dancing to the song sung by buskers in a metro tunnel in the southwestern province of Guizhou posted to YouTube on March 29 shows them singing out the chorus and the line “No room for me” at the top of their lungs.

The line seems to encapsulate the feelings of younger Chinese people in a country where most of the benefits are enjoyed by a super-wealthy elite, or by those who are under their political and economic protection.

It’s not as if they’re not trying to make a go of things.

Chinese official figures showed a spike in people returning from overseas after the lifting of the zero-COVID policy. By 2021, more than a million returning students were looking for jobs in China.

Huang Yicheng, a graduate student at the University of Hamburg in Germany, says that a lot of his former classmates at Peking University are now living the refusenik life back home, despite having graduated from Ivy League schools in the United States.

Their elite education has done little to help them find their niche amid a tanking economy and skyrocketing unemployment.

“Young people in China have no hope, and no sense of their own future,” Huang says. Under Xi Jinping, all of the important political and economic positions in China are already occupied by people in their 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s, so there is very little room for anyone younger, he says.

“Young people can’t find their niche in today’s China, so they decide to refuse to do” what’s expected of them, he says.

Even the elite are avoiding marriage

A high-earning financial executive working in southern China, who asked to be identified as Mr. V, said he moves in very well-heeled circles indeed. But even there, plenty of people are choosing to stay single and unencumbered by mortgages or children.

“First off, they feel that they have enough to live a decent life on their own, and their experience has led them to expect little from marriage,” Mr. V says.

For Mr. V’s friends and acquaintances, getting married isn’t the same as being happy, he says, adding that fears over where the country is heading also hang over this group.

“Most business people in China know what kind of state the country is in,” he says.

In major cities like Guangzhou and Shenzhen, just north of Hong Kong, getting married and buying an apartment is a massive expense that has to be carefully weighed, even in the circles that Mr. V moves in.

“Even people who have a monthly salary of 10-20 thousand yuan (U.S.$1,500~30,000) have to think twice,” he says. “There’s no way they’re getting married unless they can count on a huge amount of money from their families.”

Unhappy childhoods

Data released in 2022 showed that China’s population contracted for the first time in 60 years, with the number of newborns at a record low.

Government policies aimed at encouraging couples to have up to three children have largely fallen on deaf ears, with some frustrated young people during the grueling 2022 lockdown in Shanghai styling themselves “the last of my line.”

A final-year student at Shandong University who gave only the surname Cheng for fear of reprisals said it would be cruel to put a child through what he has had to put up with.

“They should get to grow up in a happier environment,” he says. “I can’t imagine forcing my kids to stay up late doing homework and hot-housing them through exams, which was what happened to me.”

Mr. J agrees, saying the cut-throat competition in Chinese schools puts far too much pressure on kids.

“I remember a residential community chief in Beijing in 2022 commenting that a child is a person’s weak point,” he says. “This shocked me at the time, because it showed the Chinese government’s total disregard for human rights.”

“I didn’t want another human life to become my weak point” and be used for official manipulation.

The children of peaceful critics of the ruling Communist Party are often collateral damage when their parents run afoul of the authorities.

Wang Anni, daughter of dissident Zhang Lin, was dubbed “China’s youngest prisoner of conscience” in 2012 after she was denied access to schooling and placed under house arrest alongside her father.

For Mr. J, there were also safety concerns about bringing up a child in China following a number of trafficking and child abuse scandals in recent years.

“There was also the [child abuse case] at the RYB kindergarten and the case of [hanged teenager] Hu Xinyu, all of which made me not want kids,” he says.

A Guangzhou resident who gave only the surname Tao says she is an older version of refusenik, who decided to remain child-free for political reasons.

She chose not to have kids out of concern over the level of political brainwashing they endure, starting in kindergarten.

“Now they are bringing in so-called national defense education in kindergartens … and it would be very hard as a parent to counteract that kind of education,” she says.

“Better not to have kids than to risk raising a mini-wolf warrior,” she says in a rueful reference to China’s territorial expansionism and increasingly aggressive diplomatic style.

Love on the barricades

For some, the lack of motivation to find a life partner finally found an outlet in the political white heat of the “white paper” protests of November 2022, according to Huang.

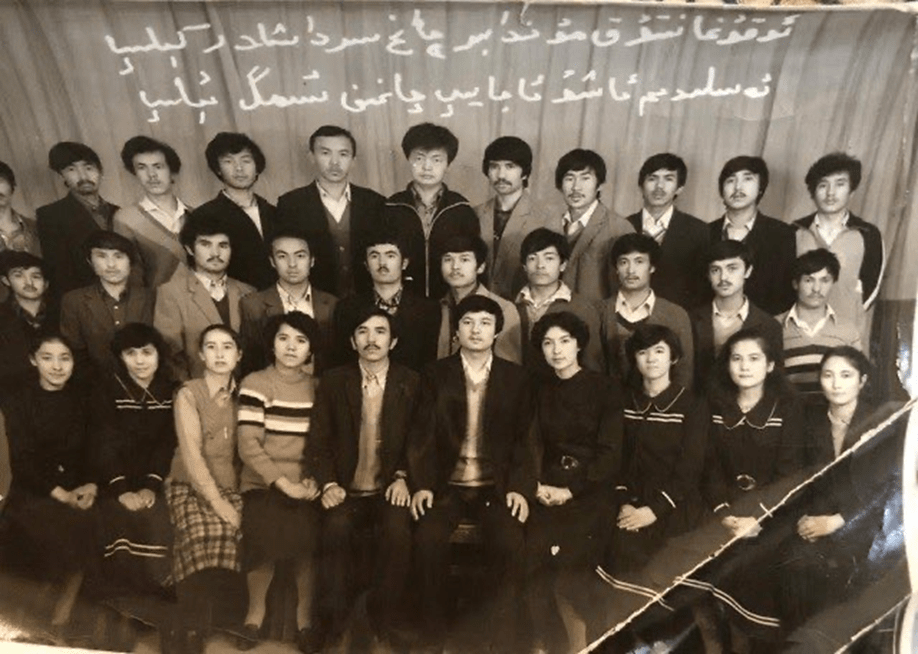

“I saw that a lot of the protesters at Urumqi Road in Shanghai said they had found a partner at those demonstrations,” he says.

“Taking part in that movement gave people hope that their lives could be better, and it’s natural to look for love when you have hope for your life,” he says, adding that he doesn’t think the refusenik approach will last.

“I don’t think it’s possible for the Communist Party to allow young people to live this way for long,” he says. “I’m pretty sure it’s going to find some way to force people to take part as cannon fodder in some kind of Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation project.”

U.S.-based current affairs commentator Tang Jingyuan said the highly centralized and authoritarian power wielded by the Chinese government is the root cause of the refusenik movement.

“This has left a huge number of young people at the lower echelons, people with no financial or political backing, who are simply unable to change their own lives or move up a social class through their own efforts,” he says.

“Whether they make an effort or don’t, the result will be the same.”

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.