Category: East Asia

Once free of charge, North Korean eBooks will cost money to access

For a country closed off from the global internet, North Korea does offer its citizens at least a few high-tech conveniences. In the Miraewon electronic library system, for example, far-flung rural residents can visit their local library to read an electronic copy of any book in the national collection in Pyongyang. The service was free of charge – until now. Authorities are telling patrons that starting in September, they must pay 1 million won, or US$120, a year – a huge sum in North Korea – angering people who use it most frequently, a resident of South Hamgyong province, north of Pyongyang, told RFA Korean on condition of anonymity for security reasons. “These measures were recently delivered to each city and county Miraewon through local party organizations, ” she said. The Miraewon, which can be translated into English as the “Future Institute”, has a portal in every city and county in North Korea, and residents can use it to access books housed in Pyongyang’s Grand People’s Study House via the intranet, an online system separate from the global internet. The Grand People’s Study House and the Kim Il-Sung Square in front of it are seen in Pyongyang, North Korea, in 2009. Credit: Reuters For some residents, this is the only way they can access materials on science and technology. The system has been a godsend for agriculture students looking to read up on farming techniques, animal husbandry, or for factory technicians in search of technical manuals or ways to improve efficiency. So the move would deprive readers of knowledge they need to more effectively do their jobs, a resident of the eastern province of South Pyongan said. “Here in Sukchon county, we’re an agricultural district, so there are farm technicians and students studying things like breed cultivation and wetland farming,” she said. “The Miraewon has physical copies of propaganda novels and the country’s masterpieces like the Complete Collection of the Works of [former leader] Kim Jong Il, but for anything related to science or technology, they must be read through the National Data Communication Network.” College students and technicians are complaining that the country prioritizes the propaganda pieces, which aren’t useful to their daily lives. “They complain … that the authorities are monopolizing the most important science and technology books and force them to access them only through the National Data Communication Network, and now they are even charging fees for it,” she said. “How can a county that hides knowledge like this ever develop economically?” Translated by Claire Shinyoung Oh Lee. Edited by Eugene Whong.

INTERVIEW: ‘I don’t know if it’s possible for me to ever return to Hong Kong’

A photography professor from the Massachusetts Institute of Art and Design has been refused entry to Hong Kong for the second time, further evidence that an ongoing crackdown on dissent under a draconian national security law could affect which foreign nationals are allowed to travel to the city. Matthew Connors, who was denied entry in 2020, immediately after the 2019 protest movement, but who is still allowed to visit North Korea, told RFA Cantonese in a recent interview that he was given a brief, bureaucratic explanation that he “didn’t meet the criteria” for entry, while the Immigration Department has declined to comment on the decision: RFA: When did you try to enter Hong Kong? Connors: On Aug. 16, I’d originally planned to come to Hong Kong as a tourist, and I especially hoped to visit art exhibitions, including the newly opened M+ museum. At the same time, it was also primarily to test the waters, because the last time I came to Hong Kong, at the beginning of 2020, I was refused entry by the Hong Kong Immigration Department, which made me always confused [about] whether I could visit Hong Kong again. And I couldn’t see any reason why I would be refused entry, and I couldn’t really understand what possible danger I could present to the Hong Kong government. I happened to be traveling in Asia for several weeks, and I was in Thailand. Since the last time I was refused entry back in early 2020, I’d had a lot of uncertainty about whether or not I’d be allowed to return to Hong Kong. And that had been bothering me. So I was hopeful I’d be able to visit and then when I didn’t really see any reason why I shouldn’t be refused, again, because the protests are no longer going on. And I couldn’t really understand what, you know, one possible danger I could present to the Hong Kong government. So I figured I would give it a try. RFA: What happened when you arrived? Connors: I was taken aside, again, by immigration, and I was told that I did not meet the qualifications for entry into Hong Kong at this time, which was a very bureaucratic answer. And it was the same reason that I was given the last time I was refused entry back in 2020. My trip was supposed to be an overnight trip, [and] I didn’t really tell anyone I knew in Hong Kong that I would be coming. Because I didn’t really know what risks that might have posed for anyone who would be seen associated with me. So when I was interviewed in the airport by immigration officers, I identified myself both as an artist and a professor that was visiting for the purpose of tourism. But despite this, in a very short interview, I was just given the generic reason that I do not meet the qualifications for entry at this time. So I knew from my past experiences that trying to get more nuanced or detailed answers from any of the immigration officers would really be futile. I actually had this feeling that no one that I actually encountered in the immigration office actually had the authority to make the decision about whether I could enter Hong Kong at the time or not. And so I really believe that I’m on a list of people whose access to Hong Kong is restricted, perhaps permanently, I’m not sure. RFA: What makes you think that? Connors: Part of the reason I think this is just the way they proceeded with the interview process, and it more or less mirrored exactly what happened to me last time. And so when I reached the immigration kiosk and presented my passport, they looked me up in the system. And then they called over immigration officer over to the window and he escorted me back to the immigration officers room and I sat in the waiting area and this was a designated area where I think they bring a lot of travelers that are flagged for further questioning, and I waited there with other travelers but ultimately, they never questioned me in this area, and they escorted me to a separate area, like a secondary interview area. I believe this is the place where they process people who they’ve already decided to refuse entry into Hong Kong. [It was] exactly where I went last time before I was refused entry. A screenshot from photographer Matthew Connors’ personal website. Credit: matthewconnors.com RFA: Do you think there’s anything you can do about your situation? Connors: I don’t know. I want to seek advice about that. You know, the last time I was refused entry, I started discussing it with an immigration lawyer, but that whole process really got derailed by the COVID lockdowns. I don’t know, to be honest. And I think that uncertainty is by design, because, you know, both with this refusal, and the sort of sweeping powers that the National Security Law gives the Hong Kong government they’re sort of instrumentalizing uncertainty in order to make people feel like their freedoms are being restricted. RFA: Did you fear this might happen when you went to Hong Kong? Connors: You know, I did. And I think some people that I consulted before left thought there was there was a higher risk, both because of the National Security Law had been passed, and because I had been denied before, but I think I had my instinct that I essentially, would be okay, that I think the worst case scenario was that I would be turned around again. I don’t have a lot of data or information to back that up. But I think I was just traveling under that assumption. This time, they did a much more rigorous search and my belongings, and then, when they escorted me through the airport, they actually took me through a separate security area and put me on a bus…

Visiting Xinjiang, Xi Jinping doubles down on hard-line policies against Uyghurs

Visiting Xinjiang for the second time in just over a year, President Xi Jinping vowed to double down on China’s hardline policies toward the 11 million mostly Muslim Uyghurs who live in the restive, far-western region. Maintaining “hard-won social stability” would remain the top priority, and that stability must be used to “guarantee development,” Xi said during a speech on Saturday in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Autonomous Uyghur Region, state media reported. Xi said it was necessary to “combine the development of the anti-terrorism and anti-separatism struggle with the push for normalizing social stability work and the rule of law.” He also told officials to further “promote the Sinicization of Islam” and “effectively control various illegal religious activities.” Under Xi, China has clamped down hard on the Uyghurs since 2017, detaining 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities in concentration camps, in reaction to sporadic terrorist attacks that Uyghurs say are fueled by years of government oppression. Beijing has also sought to destroy religious and cultural sites and eradicate the Uyghur language and its culture. The United States and legislatures of several Western countries have declared that abuses committed by China — including arbitrary detentions, torture, forced sterilizations of Uyghur women and the use of Uyghur forced labor — amount to genocide and crimes against humanity. China denies the accusations, saying its Xinjiang policies are necessary to combat religious extremism and “terrorism.” Uyghur advocates denounced Xi’s remarks, saying they pointed to more repression. “It’s crystal clear from Xi Jinping’s speech in Urumqi that the Chinese government and he intend to continue the ongoing Uyghur genocide and crimes against humanity in East Turkestan,” said Dolkun Isa, president of the World Uyghur Congress, using Uyghurs’ preferred name for Xinjiang. Noting that Xi called for more positive propaganda on Xinjiang, Isa cautioned the international community “not to be fooled” by those false images and messages. Xi last visited Xinjiang in July 2022, before the U.N.’s human rights office issued a report concluding that China may have committed genocide and crimes against humanity. China’s President Xi Jinping speaks during his visit to Urumqi in northwestern China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Aug. 26, 2023. Credit: Yan Yan/Xinhua via Getty Images ‘War on Islam’ On Monday, Rusha Abbas, executive director of the campaign for Uyghurs, said Xi’s use of the phrase “Sinicization of Islam” meant “war on Islam,” while “counter-terrorism measures” meant “mass imprisonment.” Xi also emphasizes security as the priority in Xinjiang followed by the region’s economic development, said Adrian Zenz, a researcher at the Washington, D.C.-based Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation and an expert on the Xinjiang region. “In that context he strongly emphasizes cultural assimilation, Uyghurs learning Chinese, and a Sinicization of Islam,” he said. Zenz also noted that Xi’s point on the need for Uyghurs to work in other provinces of China and along the East Coast is significant because the government has long suppressed statistics on labor transfers to other areas. “That’s actually a very important data point — an important point of evidence — and really an argument why the United States really urgently needs to add many more Chinese companies to the blacklist” related to the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. Signed into law in December 2021, the act requires American companies that import goods from Xinjiang to prove that they have not been manufactured with Uyghur forced labor at any production stage. David Tobin, a lecturer on East Asian studies at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom, said the speech signaled that the Communist Party “will not listen to criticism on its ethnic policy in general and its policies towards the Uyghur people in particular.” “Domestically, Xi Jinping is signaling to party state officials and regional leaders that he is in command and his policies must be implemented,” he said. “So, the visit is a display and an assertion of strength, but also belies a weakness to these concerns.”

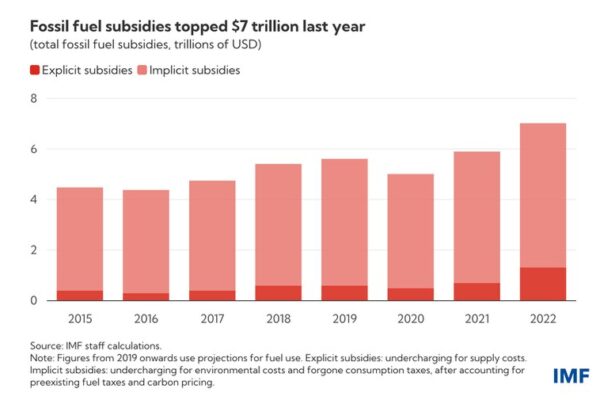

IMF: China leads as global fossil fuel subsidies hit record $7 trillion

Global fossil fuel subsidies hit a record U.S.$7 trillion, equivalent to more than 7% of global gross domestic product in 2022, the International Monetary Fund said. The subsidies are financial support from governments that make fossil fuels like oil, gas, and coal cheaper to produce or buy. Subsidies for coal, oil and natural gas in 2022 represented more than world governments spent on education and two-thirds of what was spent on healthcare. According to the IMF report released Thursday, governments provided support to consumers and businesses during the surge in global energy prices, a consequence of Russia’s incursion into Ukraine and the economic rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic. The IMF’s report comes as the world witnesses its highest average monthly temperatures on record. When burned, fossil fuels emit harmful pollutants that contribute to global warming and intensify extreme weather events. They also contaminate the air with toxins, harming our respiratory systems and other vital organs and killing millions yearly. By fuel product, undercharging for oil products accounted for nearly half the subsidies, coal another 30%, and natural gas almost 20% (underpricing for electricity accounts for the remainder), the report said. By region, East Asia and the Pacific accounted for nearly half the global subsidy, according to the IMF. Meanwhile, by country, in absolute terms, China contributed by far the most to total subsidies ($2.2 trillion) in 2022, followed by the United States ($760 billion), Russia ($420 billion), India ($350 billion), and the European Union ($310 billion). Graphic showing yearly global fossil fuel subsidies. Credit: IMF The bulk of global subsidies accounted for in the study fall into what the IMF termed implicit subsidies, which arise when governments do not adequately charge for the environmental damage caused by the combustion of fossil fuels. Such damage encompasses air pollution and climate change, with the impact forecast to grow due to the rising consumption of fossil fuels by developing countries. The IMF said explicit subsidies, in which consumers pay less than the supply costs of fossil fuels, have tripled since 2020, from $0.5 trillion to $1.5 trillion in 2022. The figure is similar to the estimates from the Canada-based think tank, International Institute for Sustainable Development, released Wednesday, that said the world’s biggest economies, the G20, provided a record $1.4 trillion in public money for fossil fuels in 2022 despite the promise to reduce spending. That includes investments by state-owned enterprises and loans from public finance institutions. The G20 nations, which cause 80% of global carbon emissions, pledged to phase out “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies in 2009. Comprehensively reforming fossil fuel prices by removing explicit fuel subsidies and imposing corrective taxes such as a carbon tax would reduce global carbon dioxide emissions by 43% below “business as usual” levels in 2030 (34% below 2019 levels) the IMF said. It added that this would be in line with keeping global warming to ‘well below’ 2 degrees Celsius and towards 1.5 degrees Celsius. “Underpricing fossil fuels implies that governments forgo a valuable source of much-needed revenue and undermines distributional and poverty reduction objectives since most of the benefits from undercharging accrue to wealthier households,” the IMF report said. “The gap between efficient and current fuel prices is often substantial given, not least, the damages from climate change and the large number of people dying prematurely from fossil fuel air pollution exposure (4.5 million a year).” The IMF said fuel price reform would avert about 1.6 million premature deaths yearly from local air pollution by 2030. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

Trafficked Lao teen says new rules include beatings if caught texting

Dozens of Lao teens trapped in a Myanmar scam compound since last year are seeing even their scant lines of communication narrowing following grave new threats from their captors. The mother of one of the trafficked teens told RFA that her daughter’s last message said anyone caught using a cellphone would be beaten 50 times with an iron bar and tied to a tree during working hours for five days. Parents of the teenagers, who were trafficked to a Chinese-owned casino in Myanmar and forced to participate in cyber scams, have long called on Lao authorities for aid in releasing their children. Authorities have previously told RFA that access is impossible due to ongoing conflict between Myanmar junta forces and the Karen National Liberation Army fighting an insurgency against the military regime. “What could we do to help our children be released from that place as we’ve waited for one year already?” the mother asked RFA. Dozens of teenagers and youth from Luang Namtha province in Laos were trafficked to “Casino Kosai” in Myawaddy on Myanmar’s eastern border with Thailand last year. There, the Laotians and scores of other young workers from the Philippines, China and elsewhere have been forced to work upwards of 16 hours a day. If they fail to dupe an unsuspecting “lonely heart” into parting with sufficient funds, they face harassment, beatings and electric shocks. The texts from the girl, who last month was beaten until she collapsed, also suggest that Chinese police have made moves to curtail some criminal activity at the casino — but only among their own citizens. While the information could not be corroborated, the mother told RFA her daughter reported that Chinese authorities arrived this week to arrest Chinese workers, though the scam compound is still in operation. Kearrin Sims, a senior lecturer at James Cook University who has researched crime in Laos, said the government could be doing far more to prevent “large-scale domestic trafficking.” “It is horrific that these vulnerable young people are being subjected to such violence and that Lao authorities are unable or unwilling to rescue them and to prevent the trafficking from occurring,” he wrote in an email. “Some form of diplomatic intervention by the Lao government is needed. We are unlikely to know what form that takes, and the government is unlikely to even acknowledge that such efforts have been made, but certainly it could request assistance from China in rescuing the victims. Perhaps that has already (unsuccessfully) happened with regard to the recent intervention by Chinese police.” Translated by Sidney Khotpanya for RFA Lao. Additional reporting by Abby Seiff.

Wagner head plane crash provokes discussion in China

Russia’s civil aviation agency said Wagner Group head Yevgeny Prigozhin was on an airplane that crashed near Moscow Wednesday. It has fueled a wave of online discussion in China, where some drew comparisons to the Chinese Communist Party’s not so distant past. No cause for the crash was provided, but Wagner-flagged Telegram accounts blamed Russian air defenses for shooting down the Embraer jet. Prigozhin’s death comes exactly two months – to the day – after the Wagner Group undertook an armed rebellion against the Russian Armed Forces, seizing control of a Russian military office in the city of Rostov-on-Don and briefly marching on Moscow. According to the Wagner Group, Prigozhin was among 10 people who lost their lives in the crash involving a private plane flying from Moscow to St. Petersburg that came down less than half an hour after taking off. The group posted what is believed to be a video of the crash on social media platforms, showing an airplane crashing and burning. They confirmed that Prigozhin had died, describing him as a hero and a patriot. They further claimed that he died at the hands of “Russian traitors.” Eyewitness footage of the crash site of a plane linked to Wagner Chief Yevgeny Prigozhin, near Kuzhenkino, Tver region, Russia, August 23, 2023, in this screen grab taken from a video. Credit: Ostorozhno Novosti/Handout via Reuters Although the news broke in the middle of the night in China, keywords related to “Prigozhin” quickly trended on the social media app Weibo, which had 255 million daily users as of March of this year. Numerous bloggers also uploaded late-night videos discussing the implications of the Prigozhin incident. China’s earlier official response to Wagner Group’s brief mutiny was muted, with a Foreign Ministry statement on June 25 calling it “Russia’s internal affair,” adding that China “supports Russia in maintaining national stability.” But some experts interviewed by the state media outlet China Daily expressed concerns about the stability of China’s friend and neighbor. “The conflict between mercenaries and the Russian army is only the tip of the iceberg about the inherent contradictions in Russian society,” said Yu Sui, a professor at the China Center for Contemporary World Studies. Challenging the leadership Many online commentators remarked on the inherent risk of standing up to autocrats in what some of them dared to call “totalitarian” states. “Prigozhin, the head of the mercenaries, clearly didn’t understand politics. Didn’t he watch House of Cards? He made the mistake of rebelling against Putin,” blogger Yojia Fleet wrote. “Breaking news! Prigozhin’s private plane crashed north of Moscow. After offending Putin, he didn’t live long. As for the cause of his death, we can only speculate,” wrote another blogger who goes by the name of Wang Xiaodong Some Chinese netizens created polls such as “Who’s behind Prigozhin’s plane crash?” to attract attention and web traffic. Online comparisons were also made to the “Russian version of the Lin Biao incident,” a reference to a top leader of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chairman Mao Zedong’s chosen successor. In 1971, he is believed to have died when his plane nosedived into the grasslands of Outer Mongolia. China’s official line is that Lin planned to assassinate Mao and when his plot failed he tried to flee Beijing for Moscow, but with insufficient fuel to complete the flight. Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, and Chinese President Xi Jinping toast during their dinner in the Moscow Kremlin, Russia, March 21, 2023. CREDIT: Pavel Byrkin, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP, File Professor Yang Haiying of Japan’s Shizuoka University said the reason that online commentators were calling the incident the “Russian version of the Lin Biao incident” was because both China and Russia are dictatorships. “Chinese citizens are paying attention to this because of the close relationship between Xi and Putin. If anyone opposes Putin, their fate is sealed, just as if anyone opposes Xi, they might follow Lin Biao’s path,” said Yang. However, Hu Ping, honorary editor of the New York-based Beijing Spring magazine, said that the relationship between Prigozhin and Putin cannot be directly compared to that of Lin Biao and Mao Zedong. He added that Lin Biao’s accident was shocking all the same, and Prigozhin’s death was dramatic, sparking discussions online. “For the CCP, this isn’t politically sensitive because it’s an external event, but a dramatic one,” said Hu. “With the Chinese government supporting Russia in the war against Ukraine and Xi Jinping often comparing himself to Putin, these factors naturally lead to speculation.” Political commentator Wang Jian said that Chinese netizens were fascinated with the latest news because of China’s good relationship with Russia, but warned that government voices might use the news to make Chinese citizens even more afraid to challenge the government. “With issues like unemployment and dropping house prices, people are anxious,” said Wang. “The government is unpredictable. The focus of Chinese netizens on external events has decreased because of the economic downturn. But government online commentators might create an atmosphere that suggests disloyalty will lead to bad consequences.” Wang also alluded to the CCP’s complete grip on the military, saying it was unlikely that China could experience a mutiny similar to Russia’s. He added that Beijing won’t need to leverage the incident to strengthen control over the military. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

Philippine officials release footage of sea standoff, as senator pushes for inquiry

A senator called Wednesday for an inquiry into how the Philippines could strengthen control of its South China Sea territory, as the coast guard released footage from a standoff between Filipino and Chinese ships in disputed waters a day earlier. The videos showed a convoy of Philippine boats and ships as they maneuvered past the China Coast Guard while sailing on a resupply mission to a remote military outpost in Ayungin Shoal (Second Thomas Shoal) in the Spratly Islands. Two Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) ships, the BRP Cabra and BRP Sindangan, escorted the convoy. They had arranged a rendezvous with civilian boats contracted by the military on Monday before setting off for Ayungin Shoal the following day, Commander Jay Tarriela said. The PCG spokesman challenged Chinese claims that its ships allowed the supply mission to proceed peacefully, and said that when the Philippine ships were within 2.5 nautical miles of reaching the shoal “we experienced dangerous maneuvers by four China Coast Guard vessels backed by four Chinese maritime militia. “They executed different ways for the Philippine Coast Guard to be separated from the supply boats so that they would be able to prevent (them) from entering the shoal,” Tarriela told reporters. Also on Wednesday, Sen. Risa Hontiveros alleged that the People’s Republic of China had continued to militarize portions of the West Philippine Sea, despite international condemnation. Manila uses that name for South China Sea waters that lie within its territory. During a speech in the Senate, Hontiveros called “for an inquiry, in aid of legislation, into further capacitating and empowering the Philippine Coast Guard to enable it to carry out its primary mission of enforcing Philippine law and upholding national sovereignty within the country’s maritime zones, particularly the West Philippine Sea.” China’s actions, she said, had led to an “unprecedented challenge to the Philippine Coast Guard’s primary mission of enforcing Philippine law, maintaining the country’s sovereignty and upholding vital national interests. In Beijing on Wednesday, China’s foreign ministry called on the Philippines “to immediately stop any actions that may complicate the situation on the ground. “Let me stress that in response to what the Philippines did, China Coast Guard took necessary law enforcement action in accordance with the law,” ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said. Tuesday’s incident followed one about two weeks ago where the China Coast Guard fired water cannons at the BRP Sierra Madre, a World War II-era ship deliberately run aground by the Philippines to serve as its military outpost in Ayungin Shoal. The shoal is about 200 km (124 miles) from the western Philippine island of Palawan, and more than 1,000 km (621 miles) from China’s nearest major landmass, Hainan island. “Now, it has become clear that China has her eye on Ayungin Shoal. The water cannons, the military laser, the removal of a naval gun cover – all these severe provocations were against Philippine vessels making their way to Ayungin,” Hontiveros told the Senate on Wednesday. “China is actively blocking these missions because she does not want any further reinforcement to our most defiant sovereign marker in the West Philippine Sea, the BRP Sierra Madre.” Videos On Wednesday, Tarriela presented a video that showed a China Coast Guard ship blocking a Philippine Coast Guard ship from entering the shoal. A second Chinese ship was positioned to intercept the Filipinos in case they got through the first cordon, the video showed. “There are also other videos that we have showing that our supply boats were being blocked by China Coast Guard vessels and the four Chinese maritime militia,” he said. “Well, this time our game plan really was to outmaneuver the China Coast Guard vessels … and make sure that the supply boats would be successful in entering the shoal,” Tarriela said. A U.S. Navy plane flies over the Ayungin Shoal during a Philippine resupply mission to the BRP Sierra Madre, Aug. 22, 2023. Credit: Aaron Favila/AP The Chinese ships issued radio challenges and warnings that said Beijing had “indisputable sovereignty” over the sea region, according to officials. The Chinese ships said they were allowing the Philippine Coast Guard and the supply boats to pass through “in the spirit of humanism.” “[W]e don’t need permission from the People’s Republic of China and Ayungin Shoal is within our exclusive economic zone. We have the sovereign right over these waters,” Tarriela said. “Secondly, it is not true that they are humane or extended humanitarian assistance.” Journalists who traveled with the Philippine Coast Guard on Tuesday posted photos of a U.S. Navy P-8 Poseidon patrol and reconnaissance plane flying overhead during the resupply mission. In Washington on Wednesday, officials at the Pentagon did not immediately respond to a BenarNews request for comment about the flight. On Monday, U.S., Australian and Philippine troops held an air assault drill in Rizal town, in the western island province of Palawan, about 108 nautical miles from Ayungin Shoal. BenarNews is an Ijreportika-affiliated online news organization.

G20 spent a record $1.4 trillion on fossil fuels in 2022, report says

The world’s biggest economies, the G20, provided a record U.S.$1.4 trillion in public money for fossil fuels in 2022 despite the promise to reduce spending, a new study by a think tank said. “The 2022 energy price crisis, brought about by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has catapulted public financial support for fossil fuels to new levels,” said the International Institute for Sustainable Development, or IISD, in its analysis, Fanning the Flames, released on Wednesday. The amount is more than double the pre-pandemic and pre-energy crisis levels of 2019 and more than four times the annual average in the previous decade, the Canada-based organization said. When burned, fossil fuels emit harmful pollutants that contribute to global warming and intensify extreme weather events. They also contaminate the air with toxins, harming our respiratory systems and other vital organs and killing millions yearly. Of the funding, the largest share of $1 trillion was allocated as fossil fuel subsidies, while $322 billion was in the form of state-owned enterprise investments and an additional $50 billion as public financial institution loans. “While much of this was support for consumers, around one-third ($440 billion) was driving investment in new fossil fuel production,” the report said, adding such support “perpetuates the world’s reliance on fossil fuels, paving the way for yet more energy crises due to market volatility and geopolitical security risks.” “These figures are a stark reminder of the massive amounts of public money G20 governments continue to pour into fossil fuels – despite the increasingly devastating impacts of climate change,” said Tara Laan, a senior associate with the IISD and lead author of the study. The IISD said the increase in investment is against the expressed pledge in the 2015 Paris Agreement and such continued investments in fossil fuels greatly hinder the chances of meeting the climate targets, as they promote greenhouse gas emissions and diminish the cost-effectiveness of renewable energy. It said that G20 nations should redirect their financial investments from fossil fuels to targeted, sustainable support for social protection and the expansion of renewable energy. This aerial photo taken on Nov. 28, 2022 shows a cargo ship loaded with coal berthing at a port in Lianyungang, in China’s eastern Jiangsu province. Credit: AFP The report comes just ahead of the pivotal G20 leaders’ conference scheduled in New Delhi on Sept. 9-10, where discussions on climate change consensus are anticipated. The meeting could set the tone for the UN’s COP28 climate change conference in Dubai in November. The report lauded the achievement of G20 chair India as it reduced its fossil fuel subsidies by 76% from 2014 to 2022 while significantly increasing support for clean energy. The IISD urged G20 leaders to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies in developed nations by 2025 and in all other countries by 2030. The world leaders had agreed to phase out “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow two years ago. “International public financing for fossil fuels has decreased in recent years but is still nearly four times greater than support for clean energy,” the report said, adding it came in the form of international aid, export credit support, and concessional financing, such as equity, grants, loans, and loan guarantees. China is among the top four largest providers of international public finance for fossil fuels in absolute dollar terms, providing $6.7 billion annually between 2019 and 2021. Japan provided $10.6 billion, while Canada provided $8.5 billion. South Korea came in third with a $7.3 billion investment. The most common fuels supported were oil and gas at 88%. The report also noted that G20 countries announced more than a quarter trillion dollars in subsidies for renewable power generation between 2020 and June 2023, with the United States, Germany and China leading the chart. “While positive, the renewable subsidies are dwarfed by subsidies for fossil fuels, which were over USD 1.4 trillion in the three years from 2020 to 2022,” the report said. The IISD also said while global investment in renewable energy reached a record high of $500 billion in 2022, it was still only around half of the investment in fossil fuels. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

Escaped Taiwanese drug lord ran trafficking ops from Cambodia prison

A Taiwanese drug lord freed from his 52-year jail sentence by masked gunmen while he was on a prison-granted dentist visit was conducting secret drug trafficking operations from Cambodia to Taiwan as recently as in 2020, despite being behind bars in Siem Reap, Radio Free Asia has learned. Court documents from Taiwanese authorities uncovered by RFA Investigative reveal that Chen Hsin Han, a Taiwanese national arrested on drug charges in Cambodia in 2009, managed to smuggle nearly 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds) of heroin to an associate in Taiwan in 2020 using a middleman he met while incarcerated. It is unclear whether Cambodian prison authorities were aware that Chen was conducting these illicit activities while in jail. But the degree to which he had access to outside resources could help explain his stunning escape on Thursday morning, when he was sprung from police custody by five men wearing masks after they charged into a dental clinic Chen was visiting. Footage from the raid shows the men pointing guns at prison guards accompanying Chen whom they had tied up while they searched for the drug lord before escaping with him. The group apparently abandoned the Lexus they drove to make their getaway, which was found several hours later with guns, masks, clothes and other materials left inside, Prison Department spokesman Nuth Savna said. “The reason the suspects could free the prisoner was because they pointed guns at the guards,” he said. “If we fought they would shoot us.” Chen Hsin Han, who was in prison for drug trafficking in Cambodia, is seen in custody in this undated photo. Credit: Fresh News Chen, 45, was arrested in 2009 and later sentenced to 52 years for drug trafficking. Before the escape, he was being held at a prison near the provincial capital of Siem Reap in northwestern Cambodia. Court records from Taiwan described his role in at least two heroin smuggling cases dating to fall 2020. According to the documents, Chen masterminded one scheme to smuggle 28 cans of what was purported to be durian paste into Taiwan through Thailand. Chen instructed an associate, Nathan Guy Garrett – said to be a U.K. national he met in Siem Reap prison – to help with the shipments, but Thai authorities discovered that the containers were filled with heroin. Weeks later, Chen instructed Garrett to transport six handbags filled with 2 kilograms of heroin into Taiwan to help distribute them there with another associate, Chan Yuxuan. Chan Yuxuan, was arrested in November 2020, along with Garrett and a driver. They were indicted in 2021. Their charging documents noted WhatsApp communications with Chen about the schemes and that Chen had the ability to remotely control drug deliveries from prison. For example, when Garrett needed to take drugs to another city in Taiwan, he immediately reported to Chen that he didn’t have money for transportation. “Chen promised to transfer the money immediately.” Chen then instructed another Taiwanese individual to assist in transferring money to Garrett promptly, the indictment said. Cambodian police have arrested six men connected to Chen’s escape this week, but he remains at large as of Friday.

Heavy artillery kills child in Myanmar’s Sagaing region

Junta heavy artillery killed a nine-year-old boy in Sagaing region’s Yinmarbin township, residents told RFA Wednesday. They said the boy, Kyaw Thiha, died Tuesday when a shell hit his home in Pay Kone village. Five other people were injured in the shelling and are being treated locally. Locals blamed the attack on troops who are providing security for the China-owned Kyae Sin Taung and Letpadaung Taung copper projects situated nearby. The military commander of the anti-junta People’s Defense Force stationed between Yinmarbin and Salingyi townships told RFA there was no reason for the shelling because his force was not fighting with junta troops Tuesday. Bloodstains on Myauk Yamar bridge, Sagaing region, where locals believe junta troops killed three villagers they arrested five days earlier, August 16, 2023. Credit: Citizen journalist Separately, villagers found the bodies of three men near a bridge over the river that runs between Yinmarbin and Salingyi townships on Wednesday, a local eyewitness from Yinmarbin Township who didn’t want to be named for security reasons told RFA. “Three bodies were found near the Myauk Yamar bridge this morning,” he said. “Two can be confirmed to be from Lel Ngauk village and the whereabouts of the other one is still under investigation. The bodies were cremated this morning.” He identified two of the dead as 44-year-old Thein Wai and 47-year-old Kyaw Nyan. Residents say the villagers were arrested around five days ago when they encountered a column of nearly 100 troops heading towards Yinmarbin township. Photographs obtained by RFA show bloodstains on Myauk Yamar bridge which locals say indicate the men were killed there. The junta spokesperson for Sagaing region, Tin Than Win, told RFA that he didn’t know about the killing of the men or the shelling of Yinmarbin. Translated by RFA Burmese. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.