Category: East Asia

Japan PM vows defense cooperation with Philippines in historic speech

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida became the first Japanese leader to address both chambers of the Philippine Congress on Saturday, underscoring a new phase in relations between the two Asian countries marked by territorial disputes with China. Calling the Philippines an “irreplaceable partner,” the Japanese prime minister said defense cooperation between the two nations, as well as with their common ally, the United States, was crucial in maintaining an “open international order based on the rule of law,” which he said was currently under serious threat. “In the South China Sea, the trilateral cooperation to protect the freedom of the sea is underway,” he told the special session of Congress, adding that Japan’s Self-Defense Forces had joined as observers in the U.S.-Philippines military drills held recently. “Through these efforts, let us protect the maritime order, which is governed by laws and rules, not by force.” Kishida arrived in Manila on Friday and met with Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. at the Malacañang presidential palace. In a joint statement, both leaders reaffirmed their support for a “rules-based approach to resolving competing claims in maritime areas” and “their commitment to freedom of navigation and overflight in the East and South China Seas.” While the Philippines and China are locked in a territorial dispute in the South China Sea, Japan and China have contending territorial claims in the East China Sea. In 2016, an international arbitration court ruled in favor of the Philippines when it rejected China’s territorial claims to most of the South China Sea on historical grounds. In recent months, China and the Philippines have engaged in increasingly tense rhetoric as both countries assert their claims over the contested waters amid standoffs at sea between Chinese and Filipino coast guards and other vessels. Kishida and Macros also agreed to start negotiating on a Reciprocal Access Agreement, a defense pact that serves as the framework for joint patrols and troop deployment for drills, among other things. Japan also committed millions of dollars to the Philippines under a security aid package to shore up the latter’s maritime defense. “From this standpoint, I confirmed with President Marcos during his visit to Japan in February that we would work together to maintain and strengthen the free and open international order based on the rule of law,” Kishida said. In his speech, the Japanese leader also acknowledged historical events, vowing that Japan would not forget the “spirit of tolerance” with which the Philippines once pardoned Japanese soldiers who committed atrocities during World War II. Meanwhile, dozens of activists with GABRIELA, a women’s advocacy group, protested outside Congress at the time, calling on the Philippine government to demand an apology from Japan for the abuse of Filipino “comfort women” who were raped and tortured during the Japanese occupation. An activist holds a placard outside the House of Representatives at the Batasang Pambansa Road in Quezon City, Metro Manila, during Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s speech at the Filipino legislature, Nov. 4, 2023. Credit: Gerard Carreon/BenarNews After Imperial Japan invaded the Philippines in December 1941, an estimated 1,000 women were sexually enslaved as “comfort women,” according to official records. Most have since died of old age. “Instead of allowing the hordes of Japanese soldiers to the Philippines, Marcos must instead confront Prime Minister Kishida about the cases of violence, abuse, and rape that the comfort women suffered in World War 2,” Cora Agovida, the group’s secretary-general, told RFA-affiliated news organization BenarNews. “Why should we allow the Philippines to be a playground for Japanese soldiers when their government can’t even apologize for the sufferings of Filipino women?” “The military access agreement being negotiated between the Philippines and Japan is part of the U.S. plan to bring more soldiers here in Asia and solidify its hold on the region,” she added, warning that more foreign troops in the Philippines could bring the country on the brink of war. Concluding his remarks, Kishida headed to the headquarters of the Philippine Coast Guard, which earlier in the day hosted Adm. Shohei Ishii, the head of the Japanese Coast Guard. He then embarked on a flight to Malaysia for an official visit. The Philippine Department of National Defense will also receive a grant of 600 million yen (U.S. $4.02 million) to purchase coastal radars as the first project under Japan’s newly launched Official Security Assistance (OSA) funds. The country also acquired 12 multi-role response vessels from Japan, which are now deployed to patrol along the archipelago’s shoreline. Japan will also provide aid grants worth U.S. $6 million to purchase trucks, bulldozers, and other heavy equipment to repair transport networks and infrastructure damaged by natural disasters in Bangsamoro, an autonomous Filipino region predominantly inhabited by Muslims and marked by conflicts between militants and the military. BenarNews is an RFA-affiliated online news organization.

Uyghur artist wins prize at prestigious art exhibit in Italy

Lékim Ibragimov was well into his career as an artist when he visited the Kizil Thousand-Buddha Caves in Xinjiang in the 1990s. It was a seminal experience that would shape his already renowned work and earn him a special commendation at one of the most prestigious exhibitions for contemporary art, the Florence Biennale in Florence, Italy. The series of rock-cut grottoes, each containing murals of Buddha, sometimes surrounded by other figures, date from the 5th to 14th century and sit on cliffs near Kizil township in Aksu prefecture. The caves, reputed to contain the most beautiful murals in Central Asia, were an important medium for Buddhist art at a time when Buddhism prevailed in Xinjiang for more than a thousand years until it was replaced by Islam around the 13th century. Now they are a source of pride and symbol of desired freedom for Uyghurs who live in the region and abroad. Ibragimov, a Uyghur graphic artist and painter who lives in Uzbekistan, explored the regional capital Urumqi and the town of Turpan. But when he went to the caves, the ancient murals and their historical richness deeply moved him. “I was particularly inspired by the Kizil Thousand-Buddha Caves [near] Kucha,” he told Radio Free Asia. “These paintings can’t be found anywhere else in the Turkic world. They are the epitome of Uyghur paintings, encapsulating the history and art of the Uyghurs. I found myself captivated.” One of the five works of Uyghur artist Lékim Ibragimov displayed at the 2023 Florence Biennale contemporary art exhibition in Florence, Italy, October 2023 Credit: Courtesy of Lékim Ibragimov Now 78, Ibragimov said he has dedicated more than 40 years to studying the cave murals and incorporating their style into his work. “Over the years, I introduced these artworks to the world with support from prominent artists who encouraged me to continue,” he said. “Through art, I paved a way for the Uyghur people. I became an academic in Russia, a national-level artist in Uzbekistan, and received many awards. I am delighted to have made this artistic contribution for the Uyghur community.” Cave frescoes Lékim Ibrahim Hakimoghli, as the artist is known among Uyghurs, has incorporated the style and colors of the cave frescoes into his abstract, surreal artwork that combines drawing, painting and calligraphy. His paintings earned him widespread recognition in Russia, Germany and other European countries after the 1990s as well as numerous awards, including the special commendation in the painting category at this year’s Florence Biennale, an event that has been held every two years since 1997. The five pieces Ibragimov presented at the exhibition were among 1,500 works by over 600 artists from 85 countries at the Oct. 14-22 event. Three of his works were of Turkic figures, outlined and accented by muted colors against a light brown background in the style of the frescoes at the Kizil, also known as Bezeklik, Thousand-Buddha Caves. Another one depicting a neighing steed trying to break free of its tether resembles a Chinese ink-and-water painting, while his rendering of an ancestral angel is reminiscent of the style and motifs of Belarussian-French artist Marc Chagall. All the works were created between 2008 and 2020. Piero Celona, the vice president and founder of the Florence Biennale, who is knowledgeable about the cave paintings in Xinjiang, expressed admiration for Ibragimov’s work. “Germany and other European countries have preserved and respected Uyghur culture, and he noticed the similarities [to the cave murals] in my paintings,” Ibragimov told RFA. “He commended my work and emphasized the Uyghur people’s yearning for freedom, predicting a brighter future for them.” Chinese suppression The award comes as the Chinese government is repressing Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples living in Xinjiang and trying to Sinicize the vast northwestern region in part by destroying Uyghur culture. Beijing has denied committing severe human rights violations in the region, despite credible reports, witness accounts and growing condemnation by Uyghur advocacy groups and the international community. One of the five works of Uyghur artist Lékim Ibragimov displayed at the 2023 Florence Biennale contemporary art exhibition in Florence, Italy, October 2023. Credit: Courtesy of Lékim Ibragimov Marwayit Hapiz, a Uyghur painter who lives in Germany and is well-acquainted with Ibragimov’s works, said the inclusion of his paintings in the Florence Biannale was a significant achievement for Uyghur art. “Lékim Ibrahim’s selections for this exhibition were a rare distinction among Turkic ethnicities,” she told RFA. “He is the sole Turkic artist to have earned this recognition.” Hapiz, who first met Ibragimov in Urumqi in 1991, calls him one of the leading artists in the field of contemporary Uyghur fine art, whose works in the style of the cave murals highlight the traditional art of Uyghurs. “I wouldn’t hesitate to call him the foremost artist in Uyghur arts,” Hapiz said. “In Europe, whenever someone inquires about painters of symbolic Silk Road paintings, his name comes up.” “Lékim Ibrahim’s paintings emanate the spirit of Uyghur art from the era of the Uyghur Buddhas,” she said. “Our Uyghur artistic legacy essentially originates from these stone wall paintings.” Narratives Through extensive research, Ibragimov developed a deep understanding of the narratives and tales depicted in the cave wall paintings and incorporated them into his creative spirit, Hapiz said. “He innovatively adapted their expression and aesthetics, establishing a unique method of painting,” she said. Ibragimov has played a pivotal role in introducing Uyghur art to the world, alongside other renowned Uyghur painters Ghazi Ehmet and Abdukirim Nesirdin, she added. “He stands as a distinctive artist from the Silk Road and Asia primarily due to his ability to reflect the ancient paintings,” said Hapiz. Other artists familiar with Ibragimov’s work took to social media to offer their congratulations and praise. The special commendation certificate and medal presented to Uyghur artist Lékim Ibragimov at the 2023 Florence Biennale contemporary art exhibition in Florence, Italy, October 2023. Credit: courtesy of Lékim Ibragimov Gulnaz Tursun, a Uyghur artist from Central Asia, who like Ibragimov, serves as a mentor…

Pakistani police crack down on Uyghurs at risk for deportation

Pakistani authorities began conducting unexpected house raids on the homes of Uyghurs living in Rawalpindi just before a government order to expel all illegal migrants who had not left the country by the start of November took effect, according to Uyghurs involved in the matter. Officials issued a warning in early October, stating that migrants without a legal residence permit in Pakistan had to leave by Nov. 1 or face deportation. The measure affects nearly 20 Uyghur families — or about 100 individuals — living in Rawalpindi, the fourth most populous city in Pakistan. Pakistani officials issued the expulsion order after dozens of people were killed in two suicide bombings in late September. Though they said that most such bombings this year were conducted by Afghan nationals, they decided to expel all migrants without a valid residence permit – including 1.73 million Afghan refugees – if they didn’t leave on their own. Most of the affected Uyghurs are descendants of individuals who migrated decades ago from Xinjiang to Afghanistan and later to Pakistan. They lack Afghan or Chinese passports and Pakistani residence permits. The Uyghurs, who have been living in a state of uncertainty in Pakistan for the past month, said authorities began sudden house raids at midnight on Oct. 31. “They are raiding homes at midnight or at 1 or 2 o’clock,” said a Uyghur man named Turghunjan who is married and has two daughters and a son. “The landlords are also telling us to leave, but we will have nowhere to sleep.” Landlords who rent homes to the Uyghurs reported some of them to the authorities, and on Nov. 1, a man named Amanullah was detained during a house search by police as part of the effort to investigate illegal migrants, the Uyghurs said. Police released Amanullah on bail five hours later. It remains unclear if authorities will deport the Uyghur families. Stopped by police Turghunjan, a relative of Amanullah, said he was abruptly stopped by police on his way home from work on the evening of Oct. 31, during which the officers checked his identity and warned him of a potential search the following day. “While I was on my way home, the police stopped me and asked me questions,” he said. “They slapped me on the face three or four times and said they would search me after Nov. 1.” “We are not Afghan, and if they deport us, where will we go?” he asked. RFA could not reach police in Rawalpindi for comment. The Uyghur families are concerned that their safety will be at risk under current Taliban control if Pakistani authorities deport them to Afghanistan. They also fear being forced back to China, where Uyghurs in the far-western Xinjiang region face repression and are subjected to severe rights abuses. “They are not leaving their homes, [and] the landlords are reporting them to the police,” said Omer Khan, founder of the Pakistan-based Omer Uyghur Trust, who has been assisting the families. Though police have threatened some Uyghurs over the past days, they have not yet arrested or deported anyone, he said. The Uyghurs sought help from the U.N. refugee agency’s office in Pakistan for years without success. But this October, the agency collected their names, addresses, and details about their families, following an early October report about their plight by Radio Free Asia. At the time, the agency also said it was investigating the situation of the Uyghur families facing deportation if they failed to comply with the government order expelling all illegal migrants. Khan said he received a reassuring call from a representative of the U.N. refugee agency, officially the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, on Nov. 2 while the Uyghurs faced harassment by police. “We didn’t ask them to come and take us,” he said. “We just need a response and decision from the U.N. about refugee status.” Neither the U.N.’s refugee agency in Geneva, Switzerland, nor its office in Pakistan responded to inquiries from RFA. Translated by RFA Uyghur. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.

Ethnic armed alliance captures 3 cities on China-Myanmar border

Allied ethnic armed groups captured three cities in northeastern Myanmar in a six-day battle, a representative of one of the groups told Radio Free Asia on Thursday. Junta troops were forced to abandon their posts on Friday when allied soldiers attacked three cities in northern Shan State, the military confirmed in a statement released Wednesday. The Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and Arakan Army gained control of the cities in an operation called 1027. Fighting took place in several townships until Monday, when the military gave up the cities of Chinshwehaw, Hpawng Hseng and Pang Hseng near the China-Myanmar border, according to junta spokesman Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun. “Here we see all kinds of propaganda that almost all the cities in northern Shan state have been controlled [by ethnic armed groups], and about where they will continue after that,” he said on junta-controlled television channel MRTV. “At this time, there are places where our government and administrative organizations and security forces have failed.” The northern allied groups have started implementing administrative systems, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army spokesperson Yan Naing told RFA. “Right now, we have full control over Chinshwehaw and Hpawng Hseng. The administrative mechanisms have been restored,” he said. “Chinshwehaw township was reformed by our administrative team. We are working to restore electricity and everything. We are working hard to make people’s lives comfortable.” Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army forces gained control of Theinni on Friday, but have not yet been able to seize the military’s camps on the other side of the town, he added. The group seized Hpawng Hseng on Monday and Pang Hseng in Muse township on Wednesday. The alliance claimed they captured nearly 90 junta army bases during the battle, but RFA has not been able to independently confirm this number. Conflict in Pang Hseng ended on Wednesday afternoon, said a local woman asking to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals. “Now, the situation has gone quiet. We stay at home and do not dare to go anywhere. If people go to market, they trade early in the morning and return home,” she said. “I heard the sounds of gunfire and small ammunition yesterday evening, not the heavy artillery anymore. If the sounds of heavy weapons are close, we run to the houses with basements.” During a routine briefing on Thursday, China’s foreign affairs ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin called for an immediate ceasefire. China tightened border security when the fighting began, locals said. “The Chinese side opens the gate if there is an emergency patient, but it is said that the war refugees are not allowed to get in,” the woman from Pang Hseng said. RFA contacted the Chinese Embassy in Myanmar, but did not receive a reply by the time of publication. Translated by RFA Burmese. Edited by Mike Firn.

Junta battalion surrenders amid Shan state ethnic offensive

An entire military battalion has surrendered to rebel forces amid an offensive by an alliance of three ethnic armies in northern Myanmar’s Shan state, according to sources with the armed resistance who called the capitulation the first of its kind in the region. All 41 members of Light Infantry Battalion 143, including a deputy commander and two company commanders, agreed to lay down their arms on Monday following talks with the Northern or “Three Brotherhood” Alliance a day earlier, Yan Naing, information officer of the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, or MNDAA, told RFA Burmese on Wednesday. “It is true that the 41 [troops] surrendered – it happened on [Oct.] 30,” said Yan Naing, whose MNDAA, based in Shan’s Kokang region along the border with China, is one of three members of the ethnic army alliance along with the Arakan Army and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army. Representatives of the Three Brother Alliance had urged commanders of the Kunlong township-based battalion to give up on Oct. 28, a day after it launched “Operation 1027” – named for the Oct. 27 date of the offensive – and simultaneously struck junta positions in the strategic Shan cities of Kunlong, Hseni, Chin Shwe Haw, Laukkaing, Namhkan, Kutkai, and Lashio, the state’s largest municipality. The MNDAA’s information department said Monday’s surrender marked the first time that a whole battalion had capitulated during an operation in northern Shan state, adding that the alliance had also confiscated a weapons cache as part of the agreement. It said 15 pro-junta militia fighters had also surrendered with their weapons on Tuesday. As part of a deal to entice junta forces to surrender, the MNDAA paid 1.5 million kyats (US$715) to each soldier from the battalion and pro-junta militia fighters that lay down their arms and escorted them to territory under their control, the group said. Operation 1027 making gains The MNDAA claims that more than 100 junta troops and pro-junta militia fighters have surrendered during Operation 1027, although its claims could not be independently verified. The Irrawaddy online journal cited the Three Brotherhood Alliance as saying that, from Oct. 27-31, it took control of 87 Myanmar military camps and three towns in Shan state – Chinshwehaw, Nawngkhio, and Hseni. In a statement issued on Tuesday, the alliance urged junta troops to give up their camps and outposts or face attack. It said those who surrender will be guaranteed safety, medical care, and other assistance that will allow them to return to their families “with dignity.” United Wa State Army soldiers participate in a military parade in Myanmar’s Wa State, in Panghsang on April 17, 2019. Credit: Ye Aung Thu/AFP The junta has yet to release any information about the surrender of its troops. Calls to junta Deputy Information Minister Maj. General Zaw Min Tun went unanswered Wednesday. Local resistance groups – including the anti-junta People’s Defense Force, or PDF – have joined in Operation 1027, which the Three Brotherhood Alliance says was launched to stop military attacks on ethnic armies in the region, get rid of online scamming rings in Kokang, and build a federal union. UWSA staying ‘neutral’ One group that will not be joining the operation is the ethnic United Wa State Army, or UWSA, which confirmed it was staying out of the campaign in a statement on Wednesday. Wa troops will “adopt a principle of neutrality” and avoid armed conflict in the Kokang region, but will retaliate against military intervention of any kind in its region, the statement said. A UWSA official confirmed to RFA that the information contained in the statement was correct. The UWSA said that the troops involved in the current conflict should “exercise restraint and pursue negotiations aimed at reaching a ceasefire.” It also said that humanitarian assistance had been provided to displaced persons who fled into the region due to the fighting. On the day Operation 1027 was launched, Kokang forces attacked Chin Shwe Haw, which was controlled by the United Wa State Army. The fighting forced some 10,000 residents of the town to flee to nearby Nam Tit for shelter, the UWSA official said. Another ethnic armed organization called the National Democratic Alliance Army, or NDAA, based in eastern Shan state has said it will not take part in the offensive and was adopting a principle of neutrality, but would “continue to maintain peace and stability” in the border region. The Three Brotherhood Alliance armies are also members of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee, or FPNCC, led by the UWSA. The seven-member coalition also includes the Shan State Progressive Party, the Kachin Independence Army, and the NDAA. Translated by Htin Aung Kyaw. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.

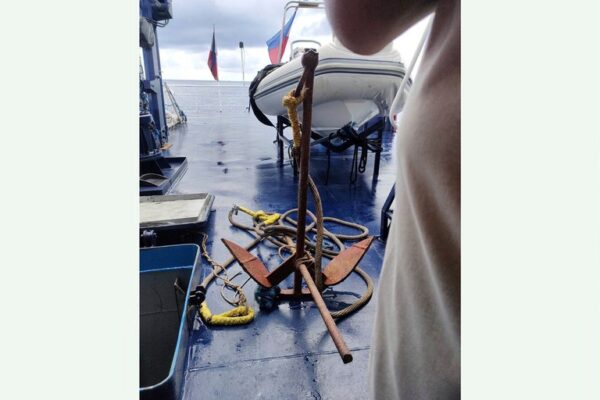

Manila rejects Beijing’s account of sea encounter

Manila for the second time this month has dismissed China’s version of a military encounter near the disputed Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea. On Monday the Chinese military said it had monitored and warned off a Philippine warship that it accused of “trespassing” into the waters around the Scarborough Shoal. Senior Col. Tian Junli, the spokesperson for China’s Southern Theater Command, said in a statement that the Philippine frigate “intruded into the waters adjacent to China’s Huangyan Dao without the approval of the Chinese government,” referring to the shoal by its Chinese name. He said the naval and air forces of the Command “tracked, monitored, warned, and restricted the Philippine military vessel according to law.” On Tuesday, Philippine authorities responded with their own version of the incident. National Security Adviser Eduardo M. Año said the Navy’s BRP Conrado Yap (PS-39) “conducted routine patrol operations in the general vicinity of Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal) without any untoward incident.” “China is again over hyping this incident and creating unnecessary tensions between our two nations,” Año said. This is the second time in three weeks that China claimed that Manila “violated China’s sovereignty over the reef” and that Chinese law enforcement forces drove Philippine ships away. Both times, the Philippines dismissed China’s claims and insisted that under international law, the Philippines had every right to patrol the area. Test of U.S. commitment “Such incidents will re-occur with increased frequency,” said Carlyle Thayer, a veteran political analyst based in Canberra, Australia. China seized Scarborough Shoal after a standoff with the Philippines in 2012 and has maintained control over it since. Manila brought Beijing to an international tribunal over its claims in the South China Sea, including of the islands, and won but China has refused to accept the 2016 ruling. “China considers Philippine vessels’ activities near the shoal a violation of China’s sovereignty and will react strongly every time,” said Thayer, adding “Beijing doesn’t want to be seen as weak.” This undated photo provided on Sept. 26, 2023, by the Philippine Coast Guard shows the anchor used to hold the floating barrier which was removed by a coast guard diver, in the Scarborough Shoal. Credit: Philippine Coast Guard via AP Another South China Sea scholar, Hoang Viet from the Ho Chi Minh City University of Law, said that the recent rapprochement between the Philippines and the United States under current Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has also contributed to China’s ramped up response. In February, Manila granted the U.S. access to four more military bases in the country. “China wants to warn those countries which, in its opinion, are seeking to move closer to the U.S.,” Viet said. “With such incidents, Beijing also wants to test Washington’s commitment in the region, especially as the U.S. is being drawn into so many global conflicts and crises,” the analyst said. The U.S. has repeatedly stated that Article IV of the 1951 U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty extends to armed attacks on Philippine armed forces, public vessels, and aircraft – including those of its Coast Guard – anywhere in the South China Sea. For its part, Manila has “embarked on a tactic of assertive transparency,” as noted by Ray Powell from Stanford University’s Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation. That means incidents in disputed waters are being reported in a timely and transparent manner. In late September, the Philippines said China had installed a 300-meter (984-foot) floating barrier to block Philippine fishermen from accessing the waters around the shoal. The Philippine coast guard carried out a “special operation” to cut the barrier and remove its anchor. Jason Gutierrez in Manila contributed to this article. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

Patriotic flag ceremonies at Hong Kong mosque ‘shock’ believers

Muslims at Hong Kong’s biggest Kowloon Mosque raised the Chinese national flag in formal ceremonies in July and October this year, to mark the city’s 1997 handover to China and China’s Oct. 1 National Day. The move has prompted shock and disappointment among some believers, who see it as a challenge to the Islamic doctrine of the supremacy of God, yet few feel safe enough to speak out for fear of political reprisals or community pressure, according to a Hong Kong Muslim who spoke to Radio Free Asia on condition of anonymity. The ceremonies come as the ruling Chinese Communist Party steps up control over religious venues across China, requiring them to support the leadership of the Communist Party of China and leader Xi Jinping’s plans for the “sinicization” of religious activity. Muslim leaders in Hong Kong have spoken to RFA Cantonese of “a developing relationship” with Chinese officials over the past 18 months, who have “suggested” they begin ceremonial displays of patriotism like flag-raising ceremonies. The ceremonies have been fairly high-profile affairs, attended by community leaders and imams, officials from Beijing’s Central Liaison Office in Hong Kong, as well as high-ranking police and local government officials. At a recent ceremony filmed by RFA, the officials stood impassively as mosque-goers performed the ceremonial movements designed to show the highest respect to the flag, then sang the Chinese national anthem, while plainclothes police observed from the sidelines. Representatives of the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government, Hong Kong government officials, and major Islamic leaders took a group photo in front of the national flag in the Kowloon Mosque. Credit: Tianji An anonymous Hong Kong Muslim said some believers are very unhappy with the move, which they say undermines the crucial Islamic principle that God is supreme, forcing them to choose between their religion and political “correctness” under the atheist ruling Chinese Communist Party. “Allah is the only highest principle there is,” said the woman, who gave only the pseudonym Miriam for fear of pressure from within her own community and of prosecution under a draconian security law imposed on Hong Kong by Beijing. “I don’t understand how people can see room for compromise here and try to argue that it’s not an issue,” she said. “I am truly and utterly shocked by this. It’s unthinkable.” Miriam said she was “deeply disappointed” in particular by the attendance of the local imam. ‘The flag of an atheist country’ The organizers said the events, which come after a number of gatherings between Muslim community leaders and Chinese officials, are indeed a nod to Beijing’s “sinicization of religion” program, and are likely to continue. “Before we didn’t have the idea to raise a flag,” Hong Kong Muslim community leader Saeed Uddin said. “Then, during the last one-and-a-half years, our relationship developed.” The Chinese national flag flies in front of the Kowloon Mosque. Credit: Screenshot from RFA video “There was a suggestion, ‘why not have [flag-raising],’” he said. “I think this is not a bad idea, to let people be more patriotic to China. They enjoy it. It’s no problem.” Yet, asked about dissenting voices among Hong Kong Muslims, he admitted to differences of opinion within the community. “We have to respect the differences of opinion,” Saeed Uddin said. But he added: “We will try to convince them.” “There was a suggestion, ‘Why not have [flag-raising],’” says Hong Kong Muslim community leader Saeed Uddin. “I think this is not a bad idea, to let people be more patriotic to China. They enjoy it. It’s no problem.” Credit: Tianji While Muslims must necessarily co-exist with secular power, they are expected to keep a certain distance, never lose sight of the supremacy of God in their actions, and avoid idolatry at all costs. Non-Islamic images and human likenesses are avoided, particularly in sacred places like mosques. For Miriam, the Chinese flag represents a totalitarian and atheist state that sees its own power as supreme, and should never be seen in a mosque. “There’s no issue with having the flag of a Muslim country in a mosque, because that country already recognizes no higher authority than God,” she said. “The country itself will be founded on Islamic precepts.” “But I’ve never seen the flag of an atheist country blatantly on display in a mosque,” she said. “Perhaps they’re using people’s lack of understanding of Islam to force this on them.” The Kowloon Mosque is seen in Hong Kong’s tourism district Tsim Sha Tsui, Oct. 21, 2019. Credit: Ammar Awad/Reuters Rizwan Ullah, honorary adviser to the Islamic Community Fund of Hong Kong, supports Beijing’s attempts to boost patriotism in the community. “We’re not raising the Chinese flag or singing the national anthem at a time of prayer,” he told RFA Cantonese in a recent interview. “So it has no effect on our beliefs, or our customs.” “History will show that this has been a correct first step,” he said, using phrasing similar to that of Chinese officials. ‘Two things can coexist’ China’s “sinicization of religion” policy, which has led churches in mainland China to display portraits of Communist Party leader Xi Jinping and prompted local officials to forcibly demolish domes, minarets and other architectural features in mosques around the country, sometimes in the face of mass protests. The Communist Party now requires all religious believers to love their country as well as their religion, and claims that patriotism is a part of Islam. Riswan Ullah agreed with this view. “I don’t see a conflict. I pray five times a day,” he said. “I raise the flag at different times of the day.” “I don’t see why being a patriot somehow makes me a bad Muslim – It’s not a zero sum equation: the two things can coexist,” he said. “I don’t see why being a patriot somehow makes me a bad Muslim – It’s not a zero sum equation: the two things can coexist,” says Riswan Ullah. Credit: Tianji But for Hong Kong’s Muslims, loving one’s country –…

Migration throws Laos’ communist government a lifeline

In a rare moment in the international spotlight, Laos was the topic of two articles published by major world media outlets in early October, although not with the sort of headlines the ruling communist party wanted to read. The BBC ran a piece on October 8 under the banner: “’I feel hopeless’: Living in Laos on the brink”. Days later, the Washington Post went with “China’s promise of prosperity brought Laos debt — and distress”, presumably because the editors thought Laos isn’t interesting enough unless tales of Chinese debt traps are also included. But both gave an accurate sense of the grim situation most Laotians, especially the young, now find themselves in. As the BBC report began: “Confronted with a barren job market, the Vientiane resident holds no hope of finding work at home, and instead aims to become a cleaner or a fruit picker in Australia.” Laotians are leaving the country in droves. My estimate is that around 90,000, perhaps more, will have migrated officially by the end of the year, joining around 51,000 who left last year and the hundreds of thousands who have moved abroad earlier. Laos has had a horrendous last few years. The landlocked Southeast Asian nation didn’t do particularly well during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the early months of 2021, it has had one of the worst inflation rates in Asia, peaking at 41.3 percent in February and still hovering at around 25 percent. The kip, the local currency, is collapsing; it hit an all-time low in mid-September when it was trading in commercial banks at 20,000 to the U.S. dollar, compared to around 8000 (US$44) in 2019. An acquaintance in Vientiane tells me that it used to cost 350,000 kip to fill up his car with diesel in 2019; today, it’s closer to 1.2 million kip (US$58) and the price keeps rising—and bear in mind that the minimum wage is now just 1.6 million kip (US$77), per a tiny increase in October. Another correspondent of mine, a foreigner, says he’s now leaving: “It’s got to the point where I’m just… done!” Motorcyclists line up for gas in Laos amid shortages, May 10, 2022. Credit: RFA The communist government is hopeless in responding, and not even the rare resignation of a prime minister last December has added any vitality to its efforts. Worse, far larger structural problems remain. The national debt, probably around 120 percent of GDP, puts Laos at risk of defaulting every quarter. It cannot continue to borrow so the authorities are jacking up taxation, and because of flagrant corruption, the burden falls more heavily than it should on the poor. Looking ahead, what is the national debt if not a tax deferred on the young and yet-to-be-born? There are not enough teachers in schools and not enough schools for students. Attendance rates have plummeted. Public expenditure on education and health, combined, has fallen from 4.2 percent of GDP in 2017 to just 2.6 percent last year, according to the World Bank’s latest economic update. More than two-thirds of low-income families say they have slashed spending on education and healthcare since the pandemic began, it also found. According to the BBC report, 38.7 percent of 18-to-24-year-olds are not in education, employment or training, by far the highest rate in Southeast Asia. A Laotian youth told me that few people want to waste money on bribes to study at university when they can quickly study Korean and try to get a high-paying factory job in Seoul. In June, an International Labour Organization update gave a summary of the numbers of Laotians leaving by official means, as estimated by the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare: Thailand 2022: 51,501 (29,319 women) 2023, up until 30 June: 42,246 (23,126 women) Malaysia 2022: 469 men Japan 2022: 312 (122 women) 2023, up until 30 June: 289 (120 women) South Korea, long-term (3 years contract) 2022: 796 (194 women) 2023, up until 30 June: 389 (54 women) South Korea, short-term seasonal workers (5 months contract) 2022: 1,356 (598 women) The first thing to note is that this is emigration by official channels. To Japan and South Korea, that official process is arduous and involves a lengthy contract procedure before leaving the country. However, the workers in South Korea can earn in a day what they would earn in a month in Laos. It’s less strenuous getting to Thailand although a considerable number of Laotians emigrate there by unofficial means, hopping across the border and not registering that they’ve left. In 2019, the Thai authorities estimated that there were around 207,000 Lao migrants working legally and 30,000 illegally, but the actual number of legal and illegal workers could have been as high as 300,000. (No one really knows how many Laotians work illegally in Thailand.) Also, consider how many Laotians have left the country so far this year compared to 2022. If we assume that emigration flows keep the same pace in the last six months of 2023 as they did in the first six, around 84,000 Laotians will have officially emigrated to Thailand by the end of this year, up from 51,000 in 2022. In April, a National Assembly delegate castigated the government for the fact that “workers have left factories in Laos for jobs in other countries because the wages paid by factories here are not keeping pace with the rising cost of living…As a result, factories in Laos are facing a labor shortage.” Saving grace? But isn’t this actually a saving grace for the communist Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (LPRP), at least in the short term? Much woe betide is made of Laos’ land-locked geography but it is rather convenient to border five countries, four of which are wealthier, if you want to avoid a situation of having disaffected, unemployed or poorly paid youths hanging around doing nothing but getting increasingly angry at their dim prospects. Conventional wisdom holds that authoritarian regimes constrain emigration as it can lead to mass labor shortages, one reason…

Ethnic alliance launches offensive on junta in eastern Myanmar

An alliance of three ethnic armies opened an offensive against Myanmar’s military regime on Friday, launching attacks on outposts in seven different locations in Shan state, in the east, including the headquarters of the junta’s Northeastern Command. At around 4:00 a.m., the Northern Alliance made up of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the Arakan Army simultaneously struck junta positions in the strategic Shan cities of Kunlong, Theinni, Chin Shwe Haw, Laukkaing, Namhkan, Kutkai, and Lashio – the state’s largest municipality. In a statement, the alliance said “Operation 1027” – named for the Oct. 27 date of the offensive – was initiated to protect the lives and property of civilians, defend its three member armies, and exert greater control over the self-administered regions within their territories. It said the operation was also part of a bid to reduce the junta’s air and artillery strike capabilities, remove the military regime from power, and crack down on criminal activities – including online scam operations – that have proliferated along the country’s northeastern border with China. Residents of Shan state told RFA Burmese that at least eight civilians were killed in Friday’s fighting, including three children. The number of combatant casualties was not immediately available, as the clashes were ongoing at the time of publishing. Pho Wa, a resident of Hopang, near Chin Shwe Haw in Shan’s Kokang region, said there were “many casualties” among junta troops and civil servants, and that key infrastructure, including bridges, had been destroyed, slowing the flow of goods in and out of the area. “Since multiple checkpoints … were raided, many customs agents, police officers and soldiers were killed,” he said. “The residents of Chin Shwe Haw have fled to [a region] administered by an [ethnic] Wa force called Nam Tit. Many are still trapped in Chin Shwe Haw city.” Residents said Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, or MNDAA, troops raided the downtown area of Chin Shwe Haw on Friday afternoon. They said inhabitants of Laukkaing were urgently preparing to flee the area ahead of an anticipated raid on the city by the armed group Kutkai and Lashio clashes In Kutkai township, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, or TNLA, soldiers attacked a pro-junta Pan Saye militia outpost on Friday morning, leading to fierce fighting, residents said. Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army soldiers seize Myanmar military security gate near Laukkai city in Northern Shan state, Friday, Oct. 27, 2023. Credit: Screenshot from AFP video A woman from Kutkai said that junta troops based in nearby Nam Hpat Kar village counterattacked with artillery fire, drawing the village into the battlezone. At least two civilians – a man and a child – were killed and five others wounded, she said, speaking on condition of anonymity due to fear of reprisal. “I think there were more than 30 artillery strikes this morning,” the woman said. “Clashes broke out when the TNLA attacked the [junta’s] outposts … That’s why they counterattacked with artillery from Nam Hpat Kar, but many of the shells fell on Nam Hpat Kar village.” A 40-year-old man was also killed in a military air strike amid fighting near Kutkai’s Nawng Hswe Nam Kut village, residents said. In Mong Ko township, fighting between junta forces and MNDAA troops has been fierce since Friday morning, and at midday the junta sent two combat helicopters to attack, residents said. Junta outposts near villages of Tar Pong, Nar Hpa and Mat Hki Nu in Lashio township, which is the seat of the military’s Northeastern Command, as well as a toll gate in Ho Peik village, were attacked Friday morning. Lashio residents said they heard the sound of heavy weapons until 7:00 p.m. on Friday and that all flights out of the city’s airport had been suspended amid the clashes. Due to the complicated and fast-moving situation in the villages around Lashio, the exact number of casualties is not yet known, but a rescue worker said that two people had been injured and sent to the hospital. Fighting in the area was tense until noon on Friday. ‘Strategic shift’ for region RFA reached out to TNLA spokesperson Lt. Col. Tar Aik Kyaw regarding the alliance operation, but had yet to receive a response by the time of publishing. Attempts to contact the MNDAA and Arakan Army, or AA, went unanswered Friday. Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government’s ministry of defense welcomed the operation in a statement. RFA was unable to reach junta Deputy Information Minister Major Gen. Zaw Min Tun for comment, but he confirmed to local media that fighting had taken place in Chin Shwe Haw, Laukkaing, Theinni, Kunlong and Lashio townships. He said that the military and police had “suffered casualties” in attacks on outposts at Chin Shwe Haw’s Phaung Seik and Tar Par bridges. Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning told reporters at a regularly scheduled press conference that Beijing is “closely following” the latest fighting along its border and called for dialogue between all parties to avoid escalation of the situation. Speaking to RFA on Friday, military commentator Than Soe Naing said that the alliance operation was retaliation for recent junta attacks on the headquarters of their ally, the Kachin Independence Army, in Lai Zar, a remote town in Kachin state on the border with China. “I consider this to be a strategic shift for the entire northern region, centered on Shan state,” he said. Translated by Htin Aung Kyaw. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.

Ailing rights lawyer Li Yuhan jailed for 6 ½ years

Chinese authorities have given a six-and-a-half year prison term to human rights lawyer Li Yuhan for “fraud” and “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble” – a charge often used to target peaceful critics of the ruling Communist Party. The Heping District People’s Court in Shenyang, in northeastern China’s Liaoning province, imposed the sentence at a hearing on Oct. 25 amid tight security and a large police presence in the streets outside, a family member told Radio Free Asia on Thursday. Li, who is in her 70s and needs assistance to walk, has spent the past six years in a detention center, so would be freed in April. Still, she said she will appeal the sentence. For her brother, Li Yongsheng, it was the first time he had seen her since her trial two years ago – after which no verdict was rendered. “She has aged significantly,” he said. “Two police officers had to assist her to walk; she was no longer able to walk normally.” He said there are also signs that her long incarceration has taken a toll on Li’s mental state. “Her thinking is confused, and her reactions are slower, and she has muddled logic,” he said. Her brother said the court building was cordoned off on all sides with iron barriers, with dozens of police and security personnel in the area. No passers-by were allowed through, and no other business was conducted in the court that day, he said. Defended rights lawyer Li is widely believed to have been targeted for her defense of prominent rights lawyer Wang Yu, who was among the first people to be detained in a nationwide operation targeting rights lawyers and activists in July 2015. “Another reason is that before her arrest, my sister had been handling other sensitive cases, various complaints and accusations, which had caused a lot of trouble for local governments,” Li Yongsheng said on Thursday. Li is being held in the Shenyang No. 1 Detention Center, where she has reportedly spent some time on hunger strike. Lawyers say China’s police-run detention centers are often overcrowded and lack facilities to ensure adequate medical care for inmates. Li has been hospitalized at least twice and given a number of medications, but applications for medical parole have been denied. A legal expert who asked to remain anonymous for fear of political reprisals told Radio Free Asia that the long delay in Li’s case was likely because the authorities were trying to elicit a “confession” from her, which she has repeatedly refused to give. He said the authorities had to sentence her for at least as long as she has already spent behind bars, but said the April 2024 release date was still a “relatively good outcome” for such a politically sensitive case. “The authorities can’t afford to admit to any error; now that they’ve detained her for that long, they have to sentence her accordingly,” the expert said. She paid ‘a huge price’ Li initially went missing on Oct. 9, 2017, and has been “at risk of torture and other ill-treatment” in the detention center, London-based Amnesty International said at the time. The group called for her immediate release. Li has paid “a huge price” for her defense of individuals unjustly accused of wrongdoing, said Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for China Sarah Brooks. “She should be released immediately and unconditionally, and the multiple allegations of her ill-treatment in detention independently investigated,” Brooks said. “Lawyer Li has been arbitrarily detained for six years [and] should be at home with her family, not in prison for merely doing her job to defend peoples’ human rights,” she added. Li Yongsheng, her brother, said the family has made written complaints over the authorities’ handling of the case, in particular questioning why it was given to the Heping district court in the first place. “Heping district isn’t her place of residence, nor where her household registration is, and it’s not where the alleged ‘crimes’ occurred, either,” he said. “So there are indeed questions about its jurisdiction here.” But he said that despite “brilliant arguments” from Li’s defense team, “we can’t influence this kind of trial.” Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.