Hong Kong warrants spark fears of widening ‘long-arm’ political enforcement by China

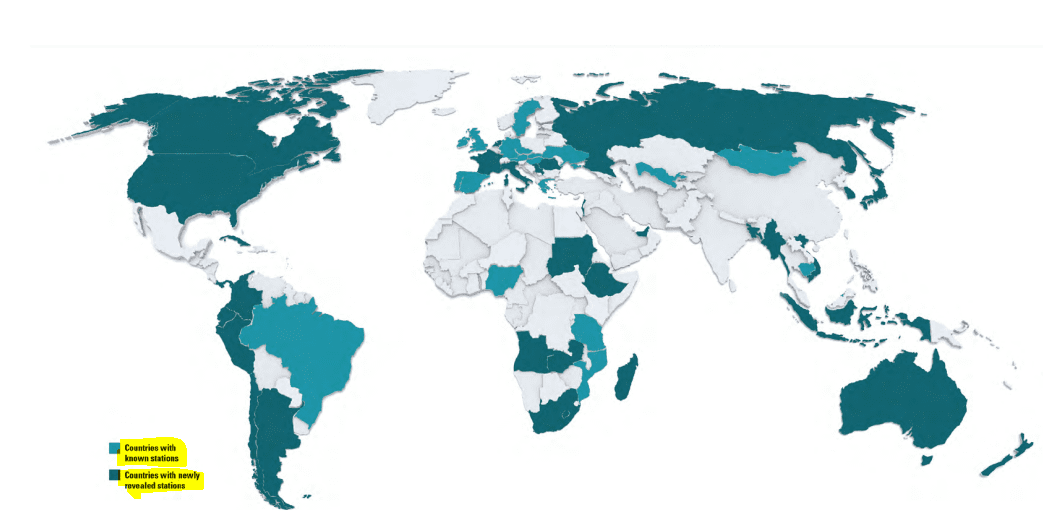

Concerns are growing that China could start using the Interpol “red notice” arrest warrant system to target anyone overseas, of any nationality, who says or does something the ruling Communist Party doesn’t like, using Hong Kong’s three-year-old national security law. Dozens of rights groups on Tuesday called on governments to suspend any remaining extradition treaties with China and Hong Kong after the city’s government issued arrest warrants and bounties for eight prominent figures in the overseas democracy movement on Monday, vowing to pursue them for the rest of their lives. “We urge governments to suspend the remaining extradition treaties that exist between democracies and the Hong Kong and Chinese governments and work towards coordinating an Interpol early warning system to protect Hong Kongers and other dissidents abroad,” an open letter dated July 4 and signed by more than 50 Hong Kong-linked civil society groups around the world said. “Hong Kong activists in exile must be protected in their peaceful fight for basic human rights, freedoms and democracy,” said the letter, which was signed by dozens of local Hong Kong exile groups from around the world, as well as by Human Rights in China and the World Uyghur Congress. Hong Kong’s national security law, according to its own Article 38, applies anywhere in the world, to people of all nationalities. The warrants came days after the Beijing-backed Ta Kung Pao newspaper said Interpol red notices could be used to pursue people “who do not have permanent resident status of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and commit crimes against Hong Kong outside Hong Kong.” “If the Hong Kong [government] wants to extradite foreign criminals back to Hong Kong for trial, [it] must formally notify the relevant countries and request that local law enforcement agencies arrest the fugitives and send them back to Hong Kong for trial,” the paper said. While Interpol’s red notice system isn’t designed for political arrests, China has built close ties and influence with the international body in recent years, with its former security minister Meng Hongwei rising to become president prior to his sudden arrest and prosecution in 2019, and another former top Chinese cop elected to the board in 2021. And there are signs that Hong Kong’s national security police are already starting to target overseas citizens carrying out activities seen as hostile to China on foreign soil. Hong Kong police in March wrote to the London-based rights group Hong Kong Watch ordering it to take down its website. And people of Chinese descent who are citizens of other countries have already been targeted by Beijing for “national security” related charges. Call to ignore To address a growing sense of insecurity among overseas rights advocates concerned with Hong Kong, the letter called on authorities in the United Kingdom, United States of America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Europe to reiterate that the Hong Kong National Security Law does not apply in their jurisdictions, and to reaffirm that the Hong Kong arrest warrants won’t be recognized. The New York-based Human Rights Watch said the “unlawful activities” the eight are accused of should all be protected under human rights guarantees in Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law. Hong Kong police on Monday, July 3, 2023, issued arrest warrants and offered bounties for eight activists and former lawmakers who have fled the city. They are [clockwise from top left] Kevin Yam, Elmer Yuen, Anna Kwok, Dennis Kwok, Nathan Law, Finn Lau, Mung Siu-tat and Ted Hui. Credit: Screenshot from Reuters video “In recent years, the Chinese government has expanded efforts to control information and intimidate activists around the world by manipulation of bodies such as Interpol,” it said in a statement, adding that more than 100,000 Hong Kongers have fled the city since the crackdown on dissent began. “The Hong Kong government’s charges and bounties against eight Hong Kong people in exile reflects the growing importance of the diaspora’s political activism,” Maya Wang, associate director in the group’s Asia division, said in a statement. “Foreign governments should not only publicly reject cooperating with National Security Law cases, but should take concrete actions to hold top Beijing and Hong Kong officials accountable,” she said. Hong Kong’s Chief Executive John Lee told reporters on Tuesday that the only way for the activists to “end their destiny of being an abscondee who will be pursued for life is to surrender” and urged them “to give themselves up as soon as possible”. The Communist Party-backed Wen Wei Po newspaper cited Yiu Chi Shing, who represents Hong Kong on the standing committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, as saying that those who have fled overseas will continue to oppose the government from wherever they are. “Anyone who crosses the red lines in the national security law will be punished, no matter how far away,” Yiu told the paper. The rights groups warned that Monday’s arrest warrants represent a significant escalation in “long-arm” law enforcement by authorities in Beijing and Hong Kong. Extradition While the U.S., U.K. and several other countries suspended their extradition agreements with Hong Kong after the national security law criminalized public dissent and criticism of the authorities from July 1, 2020, several countries still have extradition arrangements in force, including the Philippines, Portugal, Singapore, South Africa and Sri Lanka. South Korea, Malaysia, India and Indonesia could also still allow extradition to Hong Kong, according to a Wikipedia article on the topic. Meanwhile, several European countries have extradition agreements in place with China, including Belgium, Italy and France, while others have sent fugitives to China at the request of its police. However, a landmark ruling by the European Court of Human Rights in October 2022 could mean an end to extraditions to China among 46 signatories to the European Convention on Human Rights. “The eight [on the wanted list] should be safe for now, but if they were to travel overseas and arrive in a country that has an extradition agreement with either mainland China or Hong Kong, then…