When Cambodia’s Minister of National Defense General Tea Banh was seen taking a leisurely dip in the Gulf of Thailand with Chinese Ambassador Wang Wentian after a ribbon-cutting ceremony for a Cambodian naval base being built with China’s help earlier this month, no one in the region batted an eyelid.

As U.S.-China friction is getting more intense, Phnom Penh seems to have tilted towards its big neighbour, which has been offering cash and assistance to not only Cambodia but other nations in Southeast Asia.

“Cambodia and China aren’t good at hiding their relationship,” said Virak Ou, President of Future Forum, a Cambodian think tank.

“It’s obvious that we are choosing sides,” he said.

Yet most countries in the region so far remain reluctant to pick sides, and analysts say it is crucial that Washington realize the need to engage Southeast Asian nations in its Indo-Pacific strategy, or risk losing out to Beijing.

Right to decide own destiny

At the Shangri-La Dialogue security forum in Singapore, Tea Banh lashed out at what he called “baseless and problematic accusations” against the Cambodian government in relation to a naval base that Phnom Penh is developing in Ream, Sihanouk Province, with help from Beijing.

The Ream Naval Base provoked much controversy after the U.S. media reported that Hun Sen’s government was prepared to give China exclusive use of part of the base.

It would be China’s first naval facility in mainland Southeast Asia and would allow the Chinese military to expand patrols across the region.

“Unfortunately, Cambodia is constantly accused of giving an exclusive right to a foreign country to use the base,” the minister said, adding that this is “a complete insult” to his country.

Cambodia, he said, is a state that is “independent, sovereign, and has the full right to decide its destiny.”

As usual, the Cambodian defense chief refrained from naming countries involved but it is clear that both the U.S. and China are vying for influence over the ten-nation Southeast Asian grouping.

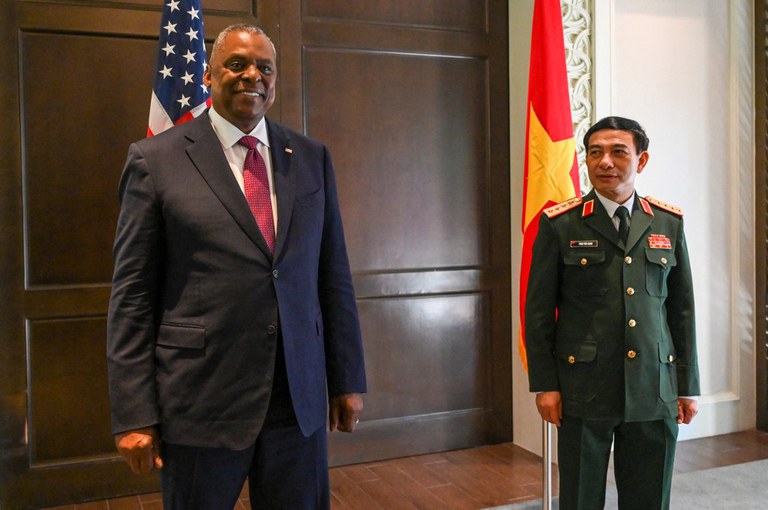

U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in his remarks at the Shangri-La forum stated that “the Indo-Pacific is our center of strategic gravity” and “our priority theater of operations.”

But questions remain on where smaller Southeast Asian nations feature in that grand strategy of the United States.

Lopsided cooperation

The region, noted Indonesia’s Minister of Defense Prabowo Subianto, “has been for many centuries the crossroad of imperialism, big power domination and exploitation.”

“We understand the rivalry between the established world power and the rising world power,” he said, implying the United States and China.

Prabowo, who joined the military in the thick of the Vietnam War and retired at the rank of Lieutenant General, told the audience at the Shangri-La Dialogue that Southeast Asian countries are “the most affected by big powers’ competition.”

Despite divisions and differences between member countries, “we’ve come to our own ASEAN way of resolving challenges,” he said.

It may seem that “we’re sitting on the fence,” Prabowo said, but this seeming inaction reflects an effort of preserving neutrality by ASEAN countries.

“Indonesia opted to be not engaged in any military alliance,” the minister said.

The same stance has been adopted by another ASEAN player – Vietnam– whose White Paper on defense policy stated “three nos” including no military alliances, no basing of foreign troops in the country and no explicit alliances with one country against another.

Yet it’s unlikely that Hanoi, often seen as anti-China as Vietnam has experienced Chinese aggression at many occasions in history, will embrace the U.S. to counter Beijing.

“It’s better to nurture a relationship with a close neighbor rather than relying on a distant sibling,” Vietnamese Defense Minister Phan Van Giang explained, quoting a Vietnamese proverb.

Two of ten ASEAN nations – the Philippines and Thailand – are U.S. treaty allies. But even in Manila and Bangkok, there have been signs of expanded cooperation with China.

“Southeast Asia and China are neighbors thanks to the geography, and their cooperation is natural,” said Collin Koh, Research Fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

Koh suggested that in order to maintain the foothold in the region, “the U.S. need to embrace and appreciate local cultures and not try to force regime changes.”

“The cooperation between the U.S. and the region has been too one-dimensional and lopsided, too security focused, and needs to expand,” he said.

Limited leverage

“Southeast Asia is a difficult region for the U.S. to grasp,” said Blake Herzinger, a Singapore-based defense policy specialist.

“The region needs to foster ties with China and Washington needs to accept and work with that,” Herzinger said, adding that it’s time to recognize that “U.S. leverage is limited in a competitive region where the opposite number is China.”

According to Southeast Asia analyst Koh, “it’s not too late for the U.S. to adjust its policy towards Southeast Asia.”

“There are still demands for an American presence here and a reservoir of goodwill that the U.S. has built over the past,” Koh said, but warned that “this may risk running dry if Washington doesn’t truly recognize the importance of engagement in the region.”

The U.S. and allies should also bear in mind regional geopolitical calculations, he said.

“Southeast Asian countries don’t want to pick sides but they find themselves being sucked into the super power competition and being pragmatic as they are, some of them are making efforts to try to benefit from it,” Koh said.

“I think the Biden administration has done a good job in relation to Southeast Asia in the last six months. Before, not so good because they had a lot on their plate,” said Bonnie Glaser, director of the Asia program at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

In her opinion, “to try benefitting from U.S.-China competition is short-sighted.”

“Countries in the region should consider a long-term strategy to hold up a rules-based world order where smaller countries also have rights to speak as they don’t want China to dictate to them what to do,” Glaser said.

On the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin met with Southeast Asia defense ministers on June 10 to discuss ways to deepen cooperation, especially in maritime security.

In May, President Joe Biden hosted the first U.S.-ASEAN Special Summit and the U.S. has just announced a new initiative to permanently deploy a Coast Guard cutter in the region.

This is a “good sign that they’re listening and trying to adjust,” said China expert Glaser.