Four years after a dam collapse that caused Laos’ worst flooding in decades, survivors who lost everything say they are tired of waiting for the government to provide them with new homes and arable land.

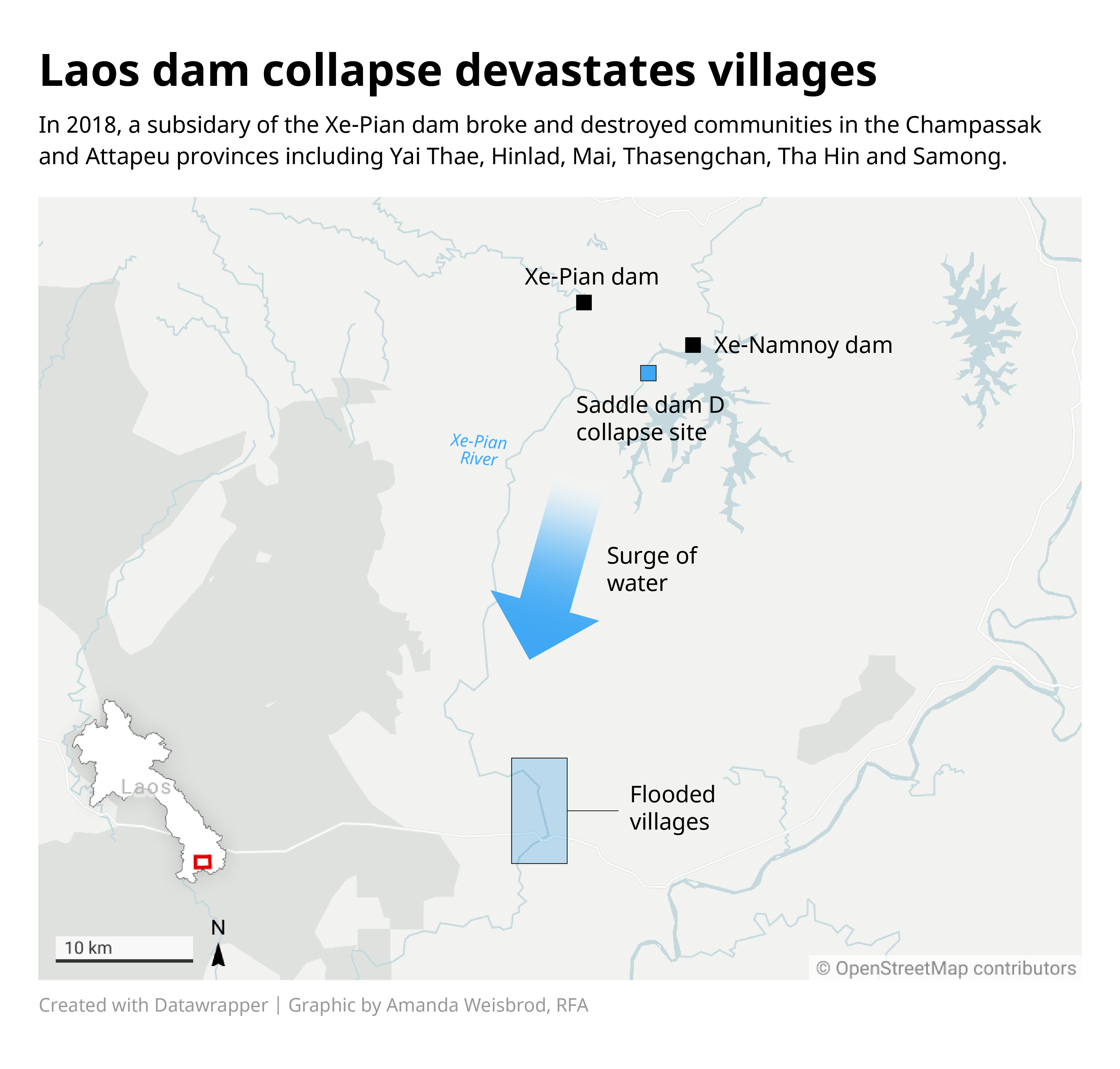

On the night of July 23, 2018, billions of cubic feet of water from a tributary of the Mekong River poured over the collapsed saddle dam D at the Xe Pian-Xe Namnoy (PNPC) hydropower project in southern Laos.

The surging water that started in Champassak province, sweeping away homes and flooding villages downstream in Attapeu province, killed 71 people and displaced 14,440 when it wiped out all or part of 19 villages.

Many of the survivors lost their homes to the rising waters and were put in metal huts in relocation villages that were intended to be temporary.

Four years on, a government that is still planning and building hydropower dams at a breakneck pace–even as it struggles with crippling debt, a sinking currency and fuel shortages–has failed to deliver on pledges to house the displaced.

“It’s already been four years since the dam collapsed. Things have improved a little bit, but we aren’t receiving rice and cash allowances anymore. We do everything to earn money to buy rice and other necessities, but we’re still struggling,” one survivor told RFA Lao.

Each family in his area were compensated with between one and two hectares (2.5-5 acres) of farmland, the source, from Attapeu’s Sanamxay district added.

UN experts Friday called on the Lao government to rectify the situation.

“It is shameful that four years since homes and livelihoods were washed away, many survivors continue to live in unsanitary temporary shelters, without access to basic services, and are still awaiting the compensation promised to them,” said the 10 experts, comprised of six special rapporteurs and a four-member working group.

“While four years have been sufficient to rebuild the dam, survivors have been left unable to rebuild their lives during all this time,” the experts said. “Not only are many still living in entirely unsuitable temporary accommodation, the compensation promised by the Lao Government and the relevant companies is being delayed, reduced or simply not provided at all, leaving the survivors with no prospect for durable solutions,” they said.

They said it was disturbing that the survivors and human rights defenders might face retaliation for bringing attention to their issues, which happened in 2019, and they noted that two other dams in the area show similar signs of impending failure as saddle dam D prior to its collapse in 2018.

“Action must be taken now to ensure that these massive hydroelectric development programmes do not cause greater harm than they do good,” the experts said.

Sanamxay district promised it would build 700 homes for the survivors there by the end of 2020, but to date, less than half of them have been completed.

“Many of the survivors who still live in metal shelters have built huts as additional living space on their plots of land, because the metal shelters are too small and hot. They live in those huts as they grow vegetables and cassava,” said the survivor, who like all unnamed sources in this report, requested anonymity for safety reasons.

“After four years, we’re still struggling to make ends meet,” a second survivor said. “We’re starting new lives. More than half are still waiting.

“Nobody is working on our new homes right now because this time of the year is rice planting season. Almost all the workers have gone home to help on the farm. They also complain about being paid late and receiving less than they expected,” said the second survivor.

The deadline for finishing the homes has been continually extended since the May 2020 agreement between Attapeu’s Public Works and Transport Department and the Vanseng Attapeu Construction Company.

Vanseng was to receive $25 million from the PNPC to complete 700 homes by the end of 2020.

But only the skeletons of 200 homes had been built by then, and the deadline slipped to 2021. An Attapeu province official told RFA at the time that there were not enough carpenters and masons to meet the original schedule.

Vanseng at that time promised to have 496 of the homes finished by the Lao New Year in April, and all 700 by the end of 2021. But by February Vanseng said only 440 would be done by April and that it would miss the anticipated completion date because not enough land had been cleared.

At an official ceremony prior to the Lao New Year, only 153 completed homes were presented to survivors.

The COVID-19 pandemic created new labor and materials shortages. Officials now anticipate the homes might be ready by the end of 2023 but possibly not until 2025, seven years after the disaster.

As of April, only 322 of the promised 700 homes were complete, Souansavanh Viyakheth, minister of Information, Culture and Tourism, announced after visiting the survivors.

A third Sanamxay district survivor told RFA that families are angry about the delays.

“Most of us are not happy with the way the so-called ‘Reconstruction Programs’ work. Four years have passed and more than half of us are still homeless,” the third survivor said.

“Living in shelters, we often run out of water in the dry season. We have received the first compensation payments for lost vehicles like cars and motorcycles but nothing yet for our other property like homes, cash, gold and jewelry. We gave all the information about these losses to the authorities a long time ago,” the third survivor said.

Families still waiting for homes also have to deal with inferior education facilities for their children, a fourth survivor of the flood said.

“One school for 500 children? It’s too crowded. Many of these kids who graduate from primary school don’t continue on to secondary school because [that school] is too far, about 10 kilometers [6.2 miles] from the villages, so they just drop out and help their parents by working in the farms,” the fourth survivor said.

An official at Attapeu Province’s Education and Sports Department told RFA that more classrooms and schools are being built.

“Of course, it’s not enough,” the official said. “We know that they don’t have enough schools and classrooms and their children have to travel far to attend secondary school.”

The families are also awaiting full compensation for their losses. An official in the Sanamxay district, where all the survivors live, told RFA that payments are delayed because the district has yet to collect all the necessary information.

“Remember that we have several thousand people who have been affected by the collapse. That’s why the payments … are late. But all of them are better off. They’ve already received land, built huts on the land, and grown vegetables and cassava on it,” the district official said.

Even so, recreating what life was like before the disaster has been difficult, a representative of a non-profit for rural development and sustainable agriculture promotion organization said.

“We’ve visited Sanamxay district to try to help create jobs and careers for the survivors. We’re concerned, though, because so much of the natural resources have been ruined, and there’s only a little bit left,” the organization representative said.

“These people rely on natural resources to survive … so many young people have left for work in the cities. Most of them don’t know what to do to make a living. The authorities have programs urging them to grow vegetables and raise cattle. In practice, the survivors have not benefited much from those programs. It’s concerning. What is the solution?” the representative told RFA.

Survivors received 835,000 kip (U.S. $55) from the dam operator as compensation for each relative who died in the disaster. The PNPC also provided a monthly stipend for living expenses of 250,000 kip ($17) per survivor initially, but now only orphans receive the stipend, which will run out when they reach 18 years old.

Laos has 79 dams in operation and is on pace to build 100 dams by 2030, Nikkei Asia reported citing Laos’ ministry of energy and mines.

The country has signed memorandums of understanding for 250 other hydroelectric projects, according to RFA’s Lao Service. The dams are part of Laos’ ambitious economic plan to become the “Battery of Southeast Asia” by selling the generated electricity to neighboring countries.

Though the Lao government sees power generation as a way to boost the landlocked country’s economy, the projects are controversial because of their environmental impact, displacement of villagers, and questionable financial and power demand arrangements.

Rural citizens remain concerned about safety, especially as the fourth anniversary of the 2018 disaster draws near.

RFA reported this week that video footage of an apparent leak at a dam in Bolikhamxay province in central Laos, which surfaced on social media on Saturday, had scared downstream residents despite assurances from the government and the dam operator that there was no danger.

“History will repeat itself. We experienced the worst dam collapse four years ago, and now this is happening again,” one downstream resident told RFA.

Translated by Max Avary. Written in English by Eugene Whong.