They signed up at job fairs to work as carpenters, bricklayers, plumbers and painters at a housing project in the North African country of Algeria and were promised round-trip air fare, room and board, and better wages than they’d earned in China. They thought working for companies serving China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was a safe bet.

When the migrant workers from Sichuan, Shaanxi, Gansu, Henan, and Hebei–China’s relatively poorer inland provinces–arrived in the country, however, they soon found themselves living in sheds without air conditioning in desert heat and facing a nightmare of withheld wages, mysterious extra fees, confiscated passports, and dismal food. Many are trapped in Algeria.

Chinese labor lawyers say their treatment not only besmirches China’s reputation, undermining the goals of the nearly 10-year-old Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of infrastructure projects aimed at boosting Beijing’s global profile, but also constitutes human trafficking under international conventions China has signed. The BRI is seen as Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature international policy.

Following up on tips received from workers who’ve been stranded some 6,000 miles (9,200 km) from home, RFA Mandarin interviewed numerous workers employed in Algeria’s Souk Ahras Province, Chinese diplomats, labor lawyers and an executive of Shandong Jiaqiang Real Estate Co. Ltd, the eastern China-based company the laborers accuse of luring them to Algeria under false pretenses.

“When I came here through an agent, I realized the situation is not good. It is worse than in China,” said Worker A, whose name has been withheld to protect him and his family from retaliation.

“The contract is good for two years, and the pay listed on the contract is more than 10,000 yuan ($1,480) per month––between 15,000 ($2,220) and 20,000 yuan ($2,960). After landing here, I made less than 10,000 yuan ($1,480) a month,” he told RFA.

“The pay is far from what was promised,” said a second man, identified as Worker B. “It is worse than what we earned in China. Here the monthly pay on average is 3,000 yuan ($444).”

When he and fellow workers “arrived here and found out that the situation was far from ideal, we wanted to go home,” said Worker A.

“We spoke with the company, and the company said ‘no.’ They said ‘Because you already signed the contract, if you go home now, that is a breach of contract.’”

According to Worker A, Shandong Jiaqiang Real Estate Co. Ltd. told the workers to “ask your family to wire 28,000 yuan ($4,145) over to pay for the penalty. After you pay the penalty, then you can go home.”

He told RFA wages were only paid every six months, with 70 percent paid, and the other 30 percent withheld until the workers fulfilled their two-year contracts.

That pay arrangement meant the workers “usually have no money to live on” and had to borrow advances against their wages.

“In the process, the workers were ripped off by other costs,” added Worker A, who said the company profited by loaning money to them at an exchange rate to the local Algerian Dinar currency that was about half the actual rate.

‘Pig food’ and hot sheds

Worker B said it took a strike by workers in September 2021 to get the company to pay the 70 percent they were due in the middle of that year.

He said the workers were told by the company: “Feel free to sue. We’re not afraid. Just sue us, go back to China to sue us.”

But a third worker involved in the dispute said that path was impossible for poor workers to take

“The lawsuit costs money. To hire someone costs money. If you file a complaint in China, you’re dragging your family in too. Who can afford to sue? said Worker C.

A chief reason the workers had to borrow money was to cook their own meals because the three daily meals they were promised under their contracts was inedible.

“To say it bluntly, the food was worse than those given to pigs. Sometimes the food was just impossible to eat,” said Worker B.

“In the winter, they gave you marinated cucumber salad or marinated tomatoes, plus two eggs per person. That’s it. Or two eggplants each person,” he said.

“The food we ate was mixed with sand and gravel. The noodles were black,” added Worker B.

“Workers in many construction sites that this company operates received the same treatment. Why? The company does not want to cook the food well, because if it’s delicious, you’d eat more. By offering lousy food, you’d pay out of pocket to buy your own food and cook your own meals,” Worker A surmised.

The make matters worse, Worker A said, the workforce had to “live in regular sheds, with no air-conditioning, no matter how hot it is.”

“In the summer, the temperature goes as high as 41 or 42 Celsius (105 or 107 Fahrenheit),” he added.

Overpriced plane tickets, improper visas

Another grievance shared by the workers in Algeria who spoke to RFA in recent months was the failure to provide return airfare to China as promised.

After checking with the Chinese Embassy in Algiers, workers who were trying to go home were told that tickets to China ran about 22,000 yuan.

“The boss has told them that a flight ticket costs ¥42,000 yuan, and we have to pay our own ticket. He wanted us to pay by ourselves,” said Worker D.

“It seemed that the ticket was around ¥22,000 yuan, and he charged you more than ¥30,000, said Worker E. “’Immigration clearance fee,’ they said,” he added.

Worker D explained that because the company applied for business visas for the workers, when the workers return to China, they have to go through departure procedures at the Algerian immigration, police bureaus, and the courts. That is the so-called “immigration clearance fee.”

“When we were recruited, we applied and submitted our passports to the recruiting agents. The agents then handed our passports to the company, which applied for the visas for us,” said Worker D.

“Supposedly we should apply for workers’ visas, which cost more but allow you to stay for one or two years. But no, the company applied for the business visa, which only allows a stay of three months,” he added.

“I asked the company to give me a work visa, but when we came, we got business visas. Then we became illegal workers. Now we have to pay out of pocket to ‘clear immigration’ and for our flight tickets,” said Worker E.

The company also took away the workers’ passports, several of them said.

“As soon as I stepped out of the airport in Algeria upon arrival, my passport was taken away. They said workers here have to buy local insurance, and they took away our passports and our IDs,” said Worker D.

The boss “keeps our passports with him, and once he has your passport, he has you,” added Worker D, who said eight out of 10 workers eventually ended up with compensation disputes.

‘There is no such thing’

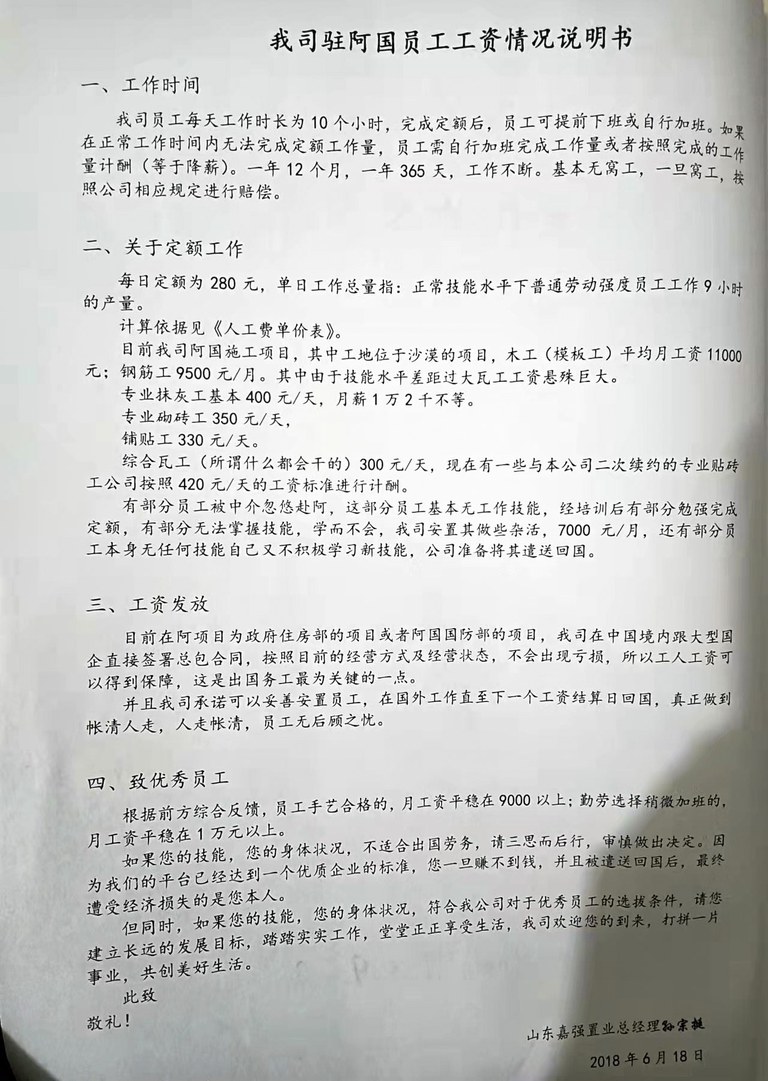

RFA reached out to Sun Zongting, the general manager of Shandong Jiaqiang Real Estate Co., Ltd., which had entered the Algerian market in 2013 to provide labor services, asking him about the workers’ complaints.

“There is no such thing. Where does this come from?” said Sun, who also denied the firm was stopping workers from returning to China.

“The reason why they didn’t return to China was because there were no flights available. With regards to payments, this is how it’s being done in Algeria. We do not owe the workers any wages.”

Pressed on the workers’ numerous complaints, Sun asked RFA: “Who said that? Give me phone numbers of those who said that. We can verify.”

“On the third or the fourth day after my arrival, I called the (Chinese) embassy. I told the embassy staff that I felt I have been conned, and that all my documents, my ID and my passports have been taken away. I asked the embassy to help me return to China,” said Worker D.

“The staff then ask me whether I’d signed a contract. I said I did when I was in Beijing. The person at the embassy told me: ‘If you are sick or if he does not pay you for your work, you can call me, but in your situation, now that you’ve come here, and you’ve signed a labor agreement…’

“The embassy staff said they did not dare to let me go,” said Worker D.

Worker D said he and his fellow workers see the embassy as working with the company.

“If you want to go to the consulate for help, for example, when a couple of people go, they’d ask you which company you work for and what your boss’s name is. Then they notify your boss. The boss then comes by car, and he sweet talks you back,” he said.

“This is what happens when two or three people go to the consulate for help. If there are more people that go, say more than a dozen of them or even two dozen, maybe the consulate will help us. Yet when there are only so few of us, it doesn’t work.”

Powerless embassy

A staffer at China’s embassy in Algiers confirmed that disgruntled workers who spoke to RFA had indeed asked for help and that the mission had helped negotiate some return plane tickets to China.

“The Embassy has helped them negotiate with the company many times, but the Embassy has no managerial power over the company to enforce the agreements, so we cannot force the company to pay up,” the embassy staffer told RFA.

“Also, the Embassy does not have any jurisdictional powers, and that’s the reason why the embassy is unable to get involved in labor disputes. Therefore, we have asked them to resolve their disputes through reasonable and legal channels in China,” added the staffer.

“We can of course speak with the company, but whether the company listens to us is another matter.”

Shandong Jiaqiang Real Estate Co., Ltd. had tried to deny it had anything to do with the BRI, but RFA found that the affordable housing project was identified in as part of the BRI framework on the website of Beijing Urban Construction, a state firm, which had also built the Algeria Opera House, a 500-unit public commercial housing tract and a fiber optic cable plant.

Worker D told RFA that the affordable housing project contract was awarded to the 14th Bureau of China Railway, the 17th Bureau of China Railway, China Hydropower, Beijing Urban Construction and other state-owned enterprises, and that Shandong Jiaqiang Real Estate Co., Ltd. was a private subcontractor.

“When the company gets the job, it’s gone through dozens of hands, with only 300,000 to 400,000 yuan left in the budget. Think about it: The profits must have been taken by the state-owned enterprises on the top of the food chain,” said Worker D.

“There isn’t much profit left. What does he do when the profit margin is slim? He exploits the workers. Basically, it’s just like China: Peeling the layers.

“The state-own enterprises peeled away one layer and subcontract the job to small businesses. The owners of small businesses then peeled away another layer, and as a result, we workers couldn’t get our money,” added Worker D.

“Some companies do have the money but won’t pay you. They know that once they’ve conned you over here, you can’t do anything. Whomever you might call for help, that help will not come.”

Lawyers see human trafficking

Peng Yan––a prominent attorney in China with 30 years specializing in state-owned enterprises, private enterprises, and foreign enterprises–told RFA the workers appeared to be in the right in the dispute in Algeria.

“If the employer breached the contract first, then based on the circumstances, the workers have the right to terminate the contract. Since the company is the party that breached the contract, the company should bear the costs of roundtrip airfares for their returns to China,” Peng said.

Yu Ping, former director of the China Office of the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative, said the workers’ complaint is a serious issue that may even entail human trafficking under the 2000 United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, to which China is a signatory.

“Under the Convention, human trafficking is defined as the act of recruiting, transporting, receiving, and sheltering human beings to another country, as actions that involve coercion, fraud, deception, and as actions whose purpose is for profits,” he told RFA.

“If you apply these three criteria to the case, then you can see that the actions of the recruiting agency, the state-owned enterprise, and the private contractor all constitute the internationally recognized definition of human trafficking,” said Yu.

“In fact, even the recruiting agent is part of this chain of human trafficking, an accomplice, or even a prime suspect. They cannot push off the responsibility to others,” he added.

Yu said the aggrieved construction workers should be able to seek legal redress back in China, which has provisions covering offenses listed as internationally recognized crimes in the UN Convention.

“Even if they lack the financial means to do so, there is an emerging channel called the ‘legal assistance system,’ in which some non-profit legal organizations or pro bono lawyers will go to court for them,” he said.

Yu also recommended that China “establish a regulatory system in the BRI program, which has oversight on the projects and the power to curtail illegal operations.”

Failing to do so, he said, will negate the international influence and goodwill that China aims to generate with the BRI program, and “on the contrary, provide opportunities for lawbreakers to make illegal profits, while China’s reputation is tarnished.”

For the workers caught broke and without plane tickets and passports in Algeria, however, the legal and international issues pale next to the personal cost of being in limbo and missing the weddings of their children or the funerals of elderly parents.

“It’s been more than two years, two-and-a-half years. I don’t know when I can go back. I fulfilled the contract, but it has become a life sentence,” said Worker B.

Translated by Min Eu. Written and edited by Paul Eckert.