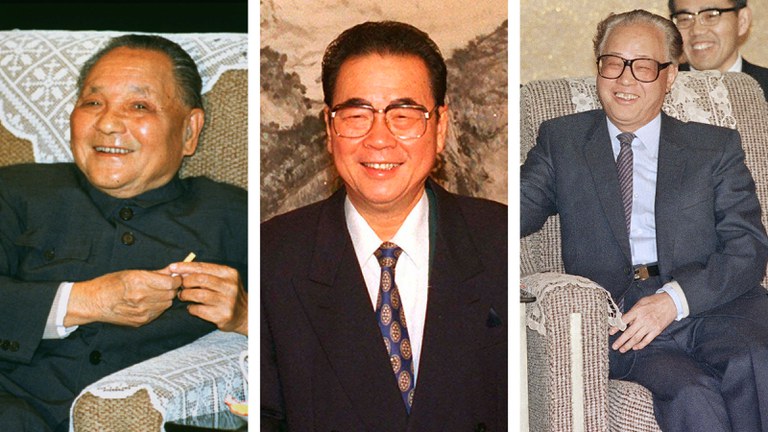

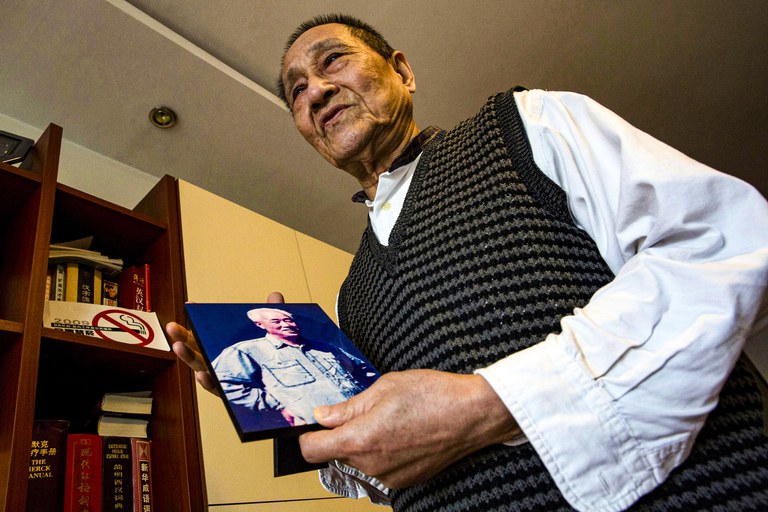

In the first part of this two-part essay, Bao Tong, a former political secretary to late, ousted Chinese leader Zhao Ziyang, comments on then Premier Li Peng’s accounts of the events leading up to the June 4, 1989 bloodshed by the People’s Liberation Army that put an end to weeks of student-led protests on Tiananmen Square. An English-language version of the diary was published in 2010 as “The Critical Moment – Li Peng Diaries.” Zhao was later removed from office and spent the rest of his life under house arrest at his Beijing home, dying in early 2005. Bao, who before the events of 1989 worked as director of the Office of Political Reform of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, served a seven-year jail term for “revealing state secrets and counter-revolutionary propagandizing.” The 89-year-old Bao, a long-time contributor of commentary on a wide range of Chinese and international issues for RFA Mandarin, including a column titled “Under House Arrest,” remains under close police surveillance in Beijing.

This article is addressed to those working in the free press and to researchers.

Let’s start with a few key events from the spring and summer of 1989:

April 15, 1989: Hu Yaobang dies. He had been one of the best-loved Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders because of his commitment to reversing millions of miscarriages of justice from the days of the Cultural Revolution, and for his advocacy of free thinking, and because his ouster at the hands of Deng Xiaoping in early 1987 elicited widespread public sympathy.

April 16, 1989: Li Jing asks then general secretary Zhao Ziyang what the official line should be on the students’ mass mourning for Hu on Tiananmen Square. Zhao answers, in front of the entire Politburo standing committee and Deng Xiaoping’s secretary: “It’s fine. Yaobang was our leader. If we mourn him ourselves, then how can we forbid the students from doing the same?

April 19, 1989: Deng Xiaoping tells Zhao Ziyang he should still go on his scheduled trip to North Korea.

April 22, 1989: As the official memorial service for Hu Yaobang concludes, Zhao announces that he will leave for North Korea on the following day.

“I have three things to say about the students,” he says.

“1. The mourning period is over, and the students should be told to go back to class. 2. There is to be no deployment of the police or military unless there is smashing and looting. 3. We should seriously study the students’ demands and resolve this through consultation and dialogue with all sectors.”

All of this was endorsed by the entire Politburo standing committee, and by Deng himself. These three points were effectively a resolution by the standing committee. Zhao also told me at the time that, with regard to political reform, we should focus all of our efforts on achieving dialogue and consultation, because that in itself was a kind of reform.

I was present for all of the above, and I take responsibility for authenticating it. As the events described below, I have no knowledge of them other than via the account provided in “Li Peng: June 4th Diary.”

Two Li Pengs

Regarding the events of April 23, we see two Li Pengs described by Li in his diary.

Let’s look at the afternoon Li Peng first. That Li Peng accompanies Zhao to the railway station, where he will take a train to North Korea, and asks him if there are any other instructions. Zhao replies: “No. Just get it done.”

Li returns to CCP headquarters in Zhongnanhai, immediately seeks out then National People’s Congress (NPC) chairman Qiao Shi, and they send out the communique together. That was the Li Peng we see in the afternoon.

Now let’s look at the evening Li Peng. Li writes that Yang Shangkun, president of the People’s Republic of China, told him to go and see Deng, that Li asked if Yang would come too, and that Yang agreed. So, did Yang and Li actually go visit Deng that evening? If so, what did they talk about? What actually happened? What made Li, Yang and Deng feel the need to meet up the moment Zhao’s back was turned? The diary doesn’t say they actually went, but neither does it say they only talked about going, but wound up not going. There’s nothing in Deng’s official annual report about any meeting, planned or actual, with Li and Yang that night. It claims that Deng didn’t meet with Li and Yang to hear their reports until the following morning, on April 25. This is entirely understandable, as Deng’s annual reports are CCP records that are kept confidential within the party.

To find out the truth of the matter, we need to go back to Li Peng’s diary and take a closer look at what Li Peng was doing and thinking on the evening of April 23. I believe with 100 percent certainty that Li Peng had figured out what Deng Xiaoping was prepared to do to quash the student protests by the evening of April 23. Because there must be a reason for Li Peng’s apparent transformation starting from that evening. Because Li wasn’t the same premier after that point, the premier who had been in such a hurry to send out documents conveying general secretary Zhao Ziyang’s three-point opinion earlier the same day. Instead, he singlehandedly rejects this important communique from general secretary Zhao Ziyang that had already been endorsed by the entire Politburo standing committee.

According to his diary, Li was worried that the students would bring back the chaos of the Cultural Revolution to China. So he decided to instruct the Beijing municipal party committee to make a report on the student unrest to the standing committee immediately. He also took unusual care to prime Wen Jiabao, then head of the General Affairs Office that coordinates the workings of the party and its leaders, not to say anything about the extraordinary meeting at which the Beijing party committee made this report to me, despite the fact that it was my bounden duty as sole political secretary to attend all meetings of the Politburo standing committee, whether scheduled or extraordinary.

Wen Jiabao told me four days later, just before the standing committee met again on April 28, that it was Li Peng who had taken the decision not to have me at the meeting on the evening of April 24. I’m grateful to Wen Jiabao for his kindness, but such an authoritative and secret plan is far more likely to have come from Deng Xiaoping and Yang Shangkun than Li Peng.

According to Li’s diary, it was Deng’s secretary who called up Li and Yang late in the evening of April 24, telling them to present themselves to Deng on the morning of April 25, to relay to him what happened at the standing committee meeting. DEng took a hard line at this meeting, claiming that “the students of Beijing are in uproar!”

This was followed with the famous editorial that appeared in the April 26 edition of the People’s Daily on behalf of the CCP Central Committee, which talked about the students as “creating turmoil,” and spreading revolutionary momentum all around the country. The biggest protest march in Chinese history followed on April 27, with not just students but regular citizens taking part.

Key omissions by Li and Deng

All of this shows us that on the evening that Zhao Ziyang left Beijing, Deng, Li and Yang must have had some kind of contact they couldn’t tell anyone about, be it direct or indirect. Why else would both Li Peng’s diary and Deng Xiaoping’s annual report both omit what actually took place on that historically important evening of April 23?

Deng was lauded throughout the CCP media as the savior of both party and nation. But were the students really the issue that was bothering Deng? Li’s diary states that, on May 21, Li Peng was anxious for a meeting with Deng as soon as possible to “resolve the matter of Zhao Ziyang.”

Deng’s secretary, primed by Deng’s Machiavellian instincts, told Li that such a meeting couldn’t take place until the People’s Liberation Army had entered Beijing, “so as to be more sure of things.”

And there you have it. They couldn’t be sure of the outcome of the meeting without a few bayonets as back-up. So, we see that the crux of the matter for both Deng and Li wasn’t so much what to do about the students but what to do about Zhao Ziyang.

We must now explore a whole new question. Did Deng Xiaoping describe the student protests as “turmoil” in a bid to stop them, or was it deliberately intended to irritate students who had already shown they weren’t afraid to take to the streets?

Imagine for the sake of argument that the students just gave up, and life went back to normal. What would have transpired after that? Would Deng and Li still have had enough justification to hold an extraordinary meeting to deal with Zhao Ziyang? Why would the party or nation even need a savior?

I should point out that while Zhao might have been seen as an adversary by Li Peng at the time, he had never been a natural enemy of Deng Xiaoping. According to the May 28 entry in Li Peng’s diary, Deng’s card-playing buddy Ding Guangan, who knew much of Deng’s internal processes, told Li Peng that Deng had been warned as early as 1988 by then president Li Xiannian that he would have to get rid of Zhao Ziyang. Deng had replied then that the time wasn’t yet ripe. Deng pondered this heavily, but didn’t get up the resolve to actually do it until May 1989. Deng wasn’t receptive to Li Xiannian’s roundabout warning because Zhao was the Great Wall upon which Deng was relying at that time, so Li Xiannian could dream on! But Deng’s answer meant that the moment Zhao innocently expressed his support for the student memorials for Hu Yaobang, he could hardly fail to secretly criticize Deng after his death, hardly fail to bring up all of the miscarriages of justice righted by Hu Yaobang, and hardly fail to become China’s Khruschev.

But was Deng Xiaoping really that petty? Hu Yaobang knew it better than anyone. He found that Deng would readily approve any injustices that had been the work of Mao Zedong, but it was well-nigh impossible to overturn any cases in which Deng himself had a hand. The cases of Gao Xiao and Liu Bocheng were a case in point. Even though 99.999 cases brought during the Anti-Rightist movement of the 1950s have been overturned, that movement was still regarded as “necessary” by Deng Xiaoping. The reason is that Deng Xiaoping headed the Anti-Rightist leadership group, back in the day.

Zhao brushed off by Deng

But this article will stay away from matters of personal integrity. The entry for the afternoon of May 13 in Li Peng’s diary is rather cryptic. It reads: “Xiaoping told president Yang Shangkun to hurry over and tell me (Li Peng) that Deng is a little deaf today, and that he didn’t hear anything of what Zhao Ziyang had told him this afternoon. “Who can decipher the meaning of this mysterious message? I happen to know what Zhao Ziyang told Deng Xiaoping on the afternoon of May 13, and I also happen to know what Deng was referring to when he replied: “All agreed. “Deng told Zhao Ziyang that afternoon, in the presence of Yang Shangkun, that he agreed with all of Zhao’s proposals for dealing with the student protests. No sooner had Zhao left than Deng turned to Zhao had told him to tell Li Peng that Deng was deaf, and had heard nothing of Zhao’s plan, thereby invalidating his apparent agreement to it.

How do I know this? Because Zhao had been seeking a meeting with Deng Xiaoping to discuss the student movement ever since he had gotten back to Beijing on April 30, and been brushed off on a daily basis by Deng. Eventually, he got a phone call on the morning of May 13 informing him that Deng would see him that afternoon. Zhao Ziyang was very pleased that day. Zhao had been working flat out during the previous 13 days, in consultation with all kinds of people about how best to engage in dialogue and consultation within the framework of democracy and the rule of law. He had also begun implementing some preliminary reforms of administration and governance among high-ranking officials, and had basically achieved a consensus at meetings of the Politburo standing committee on May 8 and at the plenary Politburo meeting on May 10. So he was anxious to hear Deng’s thoughts. I was also really excited, and spent the entire afternoon in Zhao’s personal office, which was empty.

Ziyang got back just before dinnertime.

“So what did Comrade Xiaoping have to say?” I asked him.

“Yeah, he agreed with all of it,” Zhao replied slowly, as was his way.

So I went straight over to the think-tank and told the researchers that Deng had agreed with all of it.

Backpedaling on reforms

Deng Xiaoping was a little deaf, but not very. Besides, he had all kinds of people reporting back to him on a daily basis, through a variety of channels, what Zhao was up to. He backpedaled on Zhao’s plan precisely because he knew all too well what it entailed. He was afraid Zhao would call a meeting to tell everyone about it. Why did Deng feel the need to conspire in this way? Far be it from me to stray from the official line, but it had nothing to do with clearing up a misunderstanding. If there had been one, he would have sent Yang to talk to Zhao. Why send his soldier-messenger off in such a tearing hurry to convey a secret order to Li Peng, who wasn’t even involved?

The first item in Zhao Ziyang’s package of measures was the formal withdrawal of the April 26 People’s Daily editorial, that had been issued in the name of the Politburo standing committee. I think that this was probably the focus of his briefing to Deng on the afternoon of May 13, because during the 13 days that elapsed when Deng was refusing him a meeting, Zhao had talked several times to Yang about the plan, and asked Yan Ming and Xu Jiatun to recommend it to him as well. It was Zhao’s belief that the editorial had struck the wrong tone, and was hurtful to the students, who were patriotic. But this wrong could only be righted by the person who had caused it in the first place. This was unavoidable. They would have to admit that the April 26 editorial was wrong, if they wanted to start a dialogue with the students. Without that sign of good faith, any dialogue would be pointless. And only such a show of sincerity would have the power to unite students and citizens and turn them into partners in the process of negotiation and reform.

But Yang had all along kept his views about Zhao’s plan to himself, just telling him not to rush things, to take it more slowly. That’s why I believe that this was the most important topic of discussion when Zhao finally got his meeting with Deng on May 13.

It’s highly unlikely that it wasn’t included in the “all” that Deng was referring to when he responded: “All agreed.”

I think my suppositions are well-founded, but I can’t be totally certain of them. I can only hope that a recording of this May 13, 1989 meeting between Deng and Zhao still exists, and hasn’t been destroyed.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.