The GHI is an annual report that measures and tracks hunger at global, regional, and national levels, providing insights into the severity of hunger and undernutrition across various countries. The GHI is a tool to highlight areas requiring urgent attention, but it has faced scrutiny for its methodology, scoring, and for how it portrays certain countries’ situations.

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

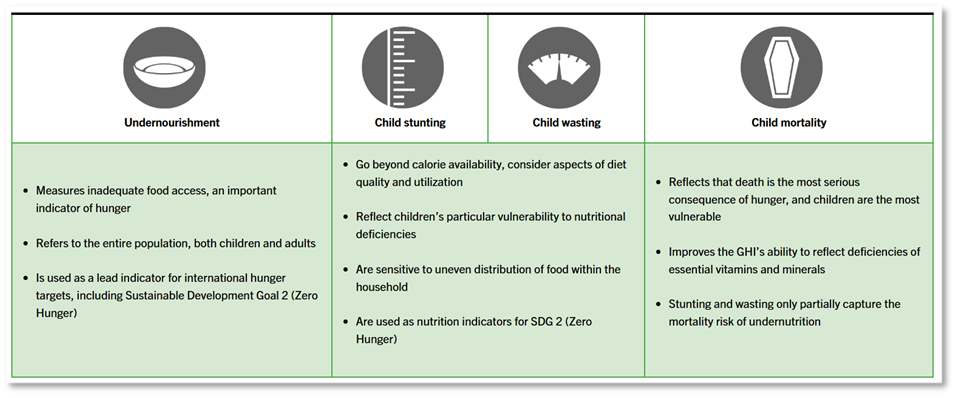

The Global Hunger Index calculates hunger levels by considering four main indicators:

Undernourishment: The share of the population whose caloric intake is insufficient;

Child Stunting: The share of children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition;

Child Wasting: The share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition; and

Child Mortality: The share of children who die before their fifth birthday, reflecting in part the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments.

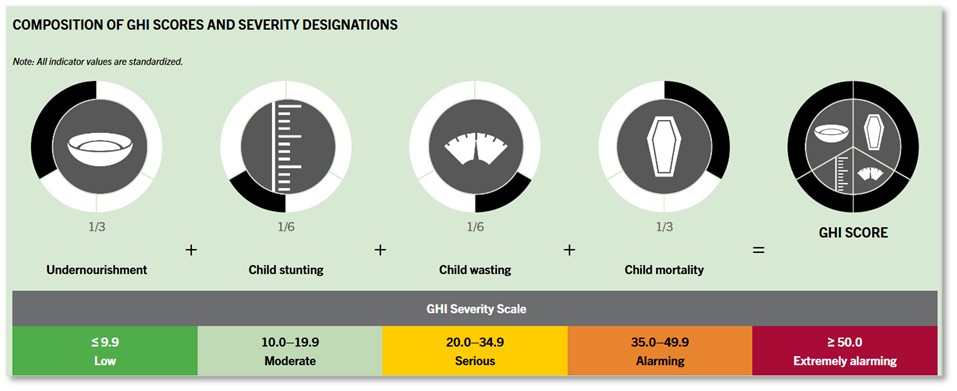

These indicators are combined to give each country a score between 0 and 100, where higher scores indicate higher levels of hunger. The scores are then categorized as “low,” “moderate,” “serious,” “alarming,” or “extremely alarming.

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

Methodological Flaws

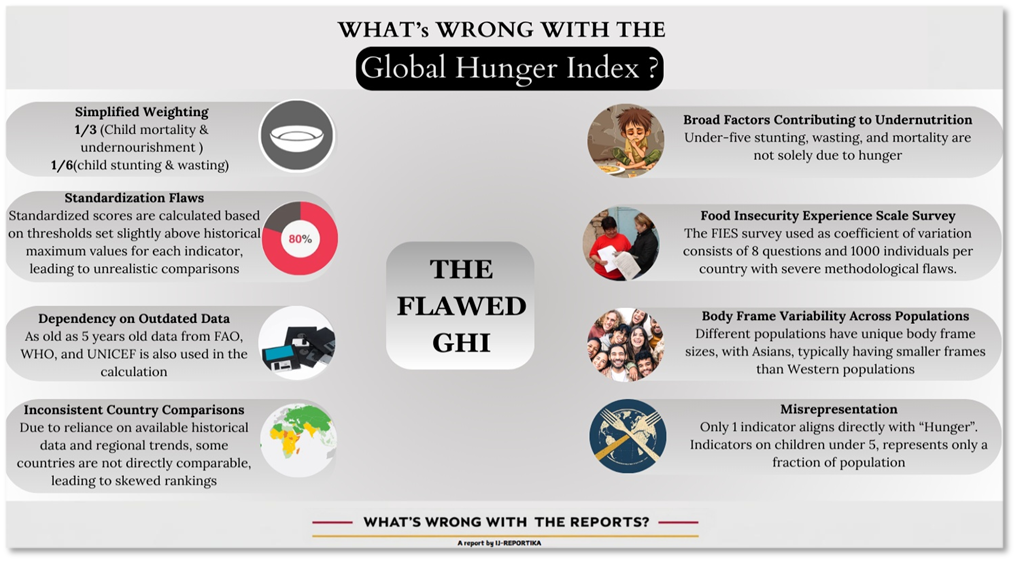

Simplified Weighting

The four indicators (undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting, and child mortality) are each weighted differently, but this approach oversimplifies the complexity of hunger. Child mortality and undernourishment each contribute one-third, while child stunting and wasting each make up only one-sixth, potentially skewing results by emphasizing certain factors over others.

Standardization Flaws

Standardized scores are calculated based on thresholds set slightly above historical maximum values for each indicator, but this approach results in unrealistic comparisons. For example, the undernourishment threshold is set at 80%, even though the highest observed value since 1988 is 76.5%. This approach distorts scores for countries with high levels of hunger, underestimating their situation.

Inconsistent Country Comparisons

Due to reliance on available historical data and regional trends, some countries are not directly comparable, leading to skewed rankings. Countries like South Sudan, where data is lacking, might be categorized conservatively, potentially underestimating their hunger crisis. Investigative Journalism Reportika suggests adopting region-based standards to better contextualize hunger evaluations. This approach would rationalize findings by accounting for local socio-economic factors, enhancing the accuracy of inter-country comparisons within similar developmental and geographic contexts.

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

THIS IS NOT HUNGER

The GHI’s methodology and choice of indicators create a skewed representation of hunger, often conflating it with broader health and nutrition issues. Following are some of the structural issues in the parameters used by GHI.

Misrepresentation of Hunger

According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), “hunger” is defined as an uncomfortable or painful sensation due to insufficient dietary energy consumption. Only one of the GHI indicators, the “proportion of undernourished population,” aligns directly with this definition. The other three indicators—wasting, stunting, and child mortality—reflect broader issues of health and nutrition rather than hunger specifically. Labelling this index as a “Hunger Index” is misleading, as it fails to capture the FAO’s definition of hunger comprehensively and specifically.

Broad Factors Contributing to Undernutrition

While hunger can lead to undernutrition, studies indicate that under-five stunting, wasting, and mortality are not solely due to hunger. For instance, international research highlights that factors such as poor sanitation, inadequate healthcare, and infectious diseases play significant roles in child mortality and malnutrition. The prevalence of stunting and wasting does not necessarily correlate with hunger alone, as other biological and environmental influences contribute to these conditions.

Research published in journals such as the American Journal of Human Biology and the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition suggests that stunting is not always a direct indicator of hunger or malnutrition. Stunting has been observed in affluent populations, indicating that genetic and environmental factors, rather than hunger alone, can influence child height.

Narrow Focus on Children Under Five

Three out of the four GHI indicators—stunting, wasting, and under-five mortality—focus exclusively on children under five, representing only a fraction of the overall population. This narrow demographic focus is problematic as it cannot adequately represent the hunger levels of the entire population. By heavily weighting these indicators (two-thirds of the total index weight), the GHI creates a distorted picture of hunger, disproportionately reflecting issues faced by young children and overstating the hunger problem.

Double-Counting of Undernourished Population

The GHI includes the undernourished population indicator, which already accounts for undernourished children. This creates an upward bias in the index by effectively double-counting the population of undernourished children. The issue of multicollinearity among the selected indicators—due to their correlation with each other—leads to statistically biased results, further impacting the index’s accuracy.

Body Frame Variability Across Populations

Different populations have unique body frame sizes, with Asians, typically having smaller frames than Western populations. Consequently, the standard indicators for obesity and undernutrition may not accurately apply to all populations. For instance, international studies argue that overweight and obesity classifications for Asians should have lower cut-offs. This variability implies that standard GHI indicators does not effectively capture the nutritional status in countries with smaller average body frames.

Data Limitations

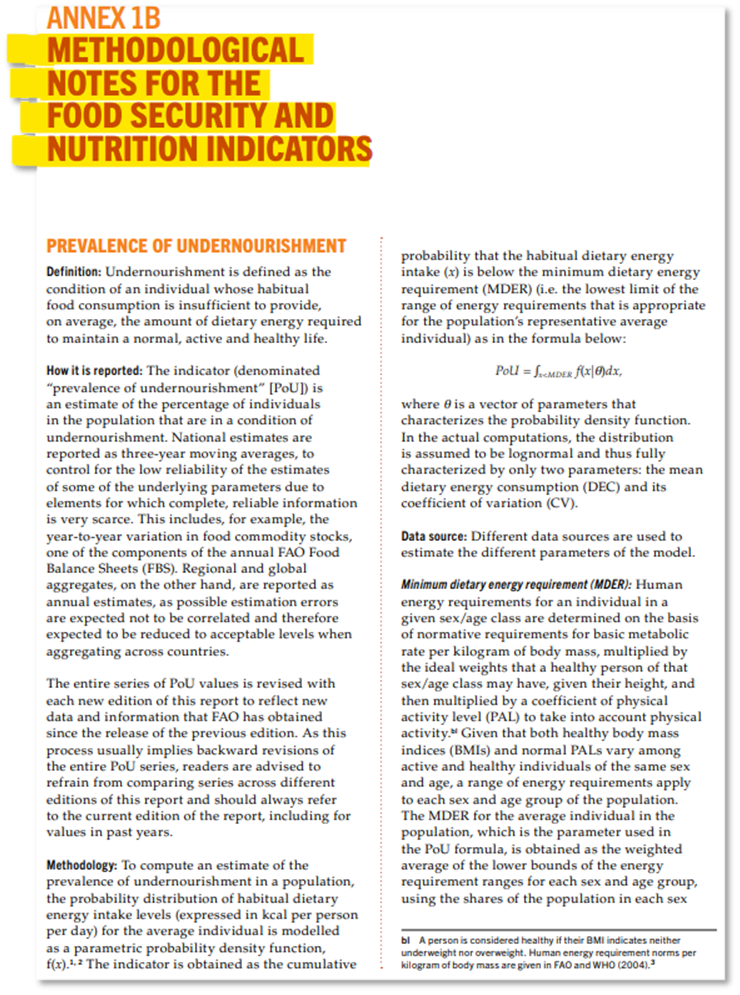

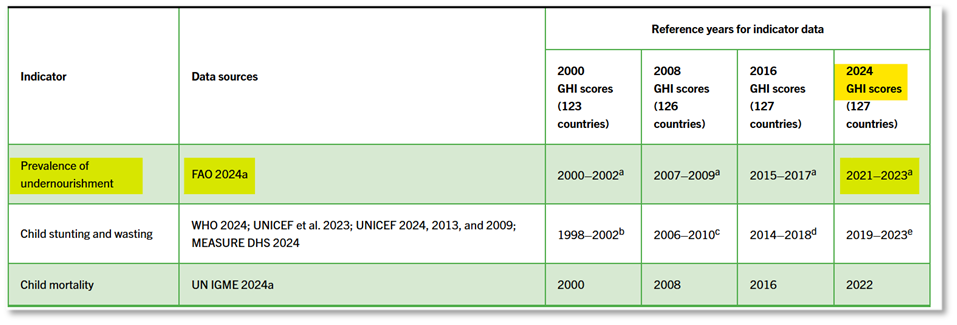

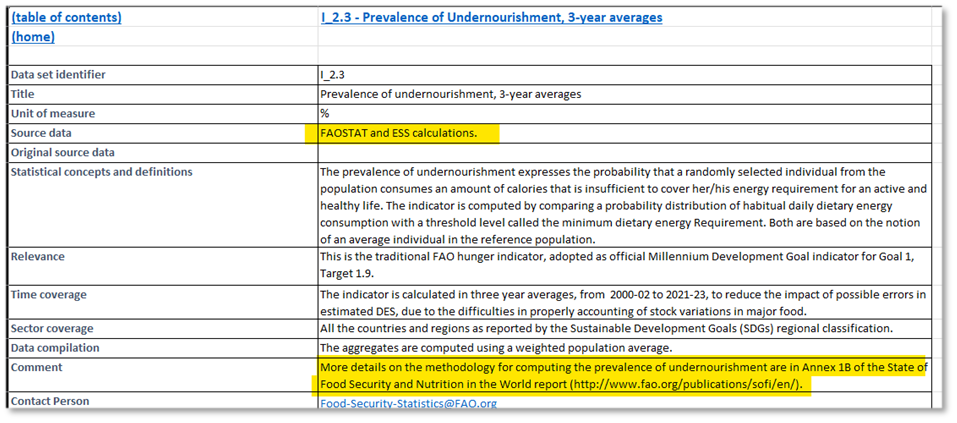

Our investigation into the data sources of the Global Hunger Index (GHI) underscores several methodological limitations in calculating the “Prevalence of Undernourishment” (PoU), a key indicator within the GHI. PoU estimates depend on various components, including Dietary Energy Consumption (DEC), Minimum Dietary Energy Requirement (MDER), and the coefficient of variation (CV), each with its own set of data sources and assumptions. DEC values are primarily derived from the FAO’s Food Balance Sheets (FBS) and are supplemented by household surveys in some cases. However, due to the limited frequency of these surveys, DEC is estimated through dietary energy supply (DES) data. Waste factors are then applied to calculate DEC values, but the use of outdated or extrapolated waste data introduces potential inaccuracies in determining energy availability at the national level.

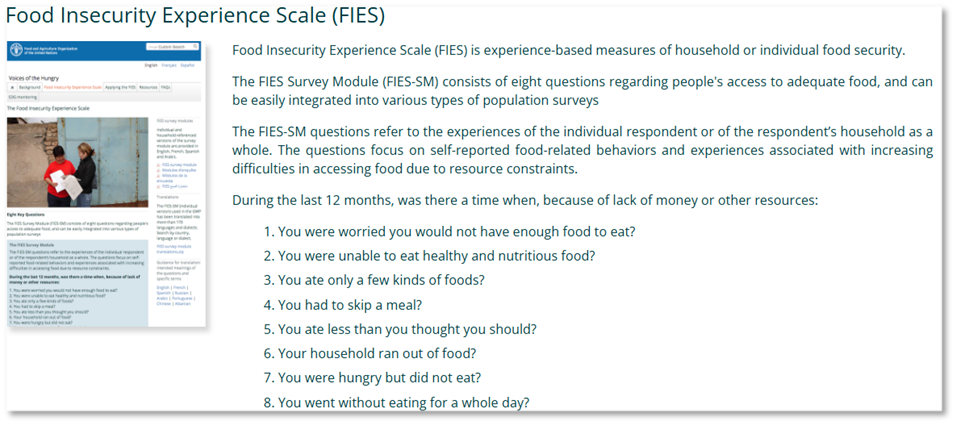

The reliance on MDER introduces further challenges. MDER estimates use demographic information on age, sex, median height, and activity level from sources like the UN World Population Prospects and Demographic Health Surveys (DHS), though these sources are updated infrequently. This creates potential discrepancies when population structures shift due to demographic or health changes that aren’t captured in real-time data. Additionally, the coefficient of variation (CV) attempts to account for income-based differences in energy consumption across households and individual variation within households. CV calculations often rely on older data, such as past surveys or FIES data, which are adjusted based on severe food insecurity trends. This adjustment methodology assumes food insecurity changes correlate directly with PoU shifts, though this assumption is not fully account for complex factors influencing hunger.

The Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) further compounds these limitations. The FIES survey consists of eight questions regarding food access and is conducted among small, random samples, often around 1,000 individuals per country (or slightly higher for larger countries like China and India), with a mix of face-to-face and telephone methods. This small sample size, coupled with limited access to certain demographics—particularly in regions relying on telephone interviews—raises questions about the representativeness of FIES data.

When national data is missing or inconsistent, estimates are imputed based on regional trends or historical data, creating an additional layer of assumptions that does not accurately reflect present conditions. Such methodological compromises, when layered onto other PoU indicators, weaken the reliability of the GHI in accurately capturing and ranking global hunger trends.

Overall, the cumulative effects of these data limitations and assumptions call into question the accuracy and timeliness of PoU estimates, and, by extension, the GHI rankings. The use of three-year averages, outdated demographic data, and projected variations often overlook the real-time dynamics of food insecurity in countries experiencing rapid change.

Download, Read and Share the comprehensive report by Ij-Reportika: Link

Unexpected or Flawed discrepancies

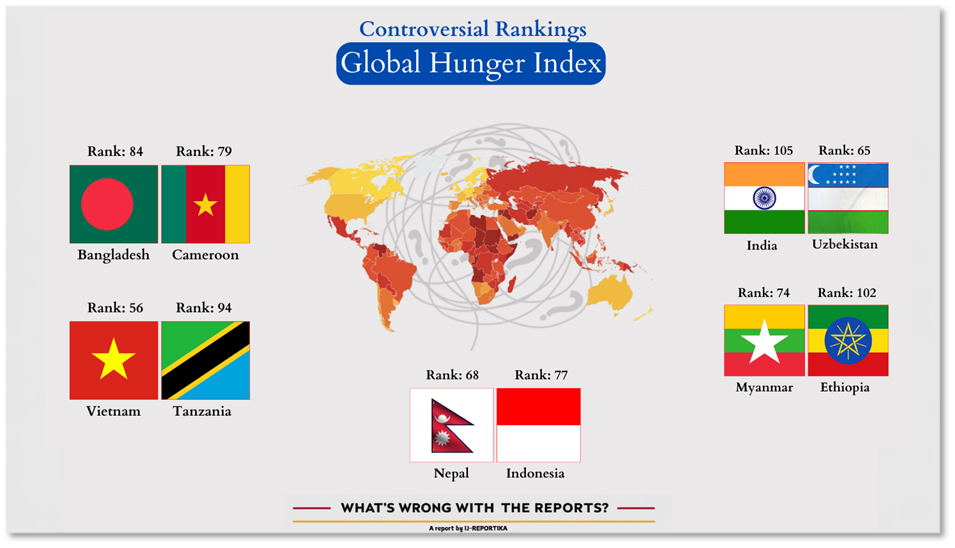

Vietnam (Rank: 56) vs. Tanzania (Rank: 94): Vietnam, ranked 56th, has achieved remarkable success in reducing hunger through agricultural innovation and export-driven food production. Tanzania, at 94th, continues to grapple with high rates of food insecurity and dependence on subsistence farming. The ranking disparity does not reflect the stark differences in hunger mitigation strategies and outcomes between the two nations.

India (Rank: 105) vs. Uzbekistan (Rank: 65): India, ranked 105th, faces significant challenges in malnutrition and hunger, but it also has extensive food distribution programs like the Public Distribution System (PDS) and large-scale agricultural production. Uzbekistan, ranked significantly higher at 65, has far fewer resources and ongoing concerns about equitable food access and distribution due to governance issues. The rankings fail to account for India’s strides in food security infrastructure compared to Uzbekistan’s limited reach.

Bangladesh (Rank: 84) vs. Cameroon (Rank: 79): Bangladesh, ranked 84th, has made significant strides in combating hunger through microfinance initiatives and women-led agriculture. Cameroon, at 79th, struggles with internal conflicts that disrupt food production and distribution. The rankings fail to adequately reflect Bangladesh’s relative success prior to 2024 in stabilizing food security compared to Cameroon’s ongoing challenges. (Note: It doesn’t take into account the recent internal challenges in Bangladesh and the impact on the food security)

Myanmar (Rank: 74) vs. Ethiopia (Rank: 102): Myanmar, ranked 74th, is grappling with political instability that directly impacts food availability, yet it is ranked significantly higher than Ethiopia, at 102nd. Ethiopia’s government has implemented large-scale hunger relief programs in response to droughts and conflict. The rankings fail to capture the immediate impact of Myanmar’s political turmoil on food security compared to Ethiopia’s concerted mitigation efforts.

Nepal (Rank: 68) vs. Indonesia (Rank: 77): Nepal has made commendable progress in reducing hunger despite its limited resources, challenging terrain, and reliance on subsistence agriculture. However, in 2022, 20.3% of Nepal’s population lived below the national poverty line, highlighting the nation’s ongoing struggles with poverty. In contrast, Indonesia, ranked lower, is more economically developed country.

By March 2023, Indonesia’s poverty rate was 9.36%, having declined from 10.2% in September 2020. Despite its relatively lower poverty rate and greater economic capacity, Indonesia faces challenges like unequal food distribution. The rankings however, do not fully reflect Indonesia’s potential and resources compared to Nepal’s more significant structural challenges.

Controversies

Following are the controversies surrounding the Global Hunger Index (GHI) raised by different countries:

- China: China has raised objections over data inconsistencies in the GHI, particularly regarding Dietary Energy Supply and food distribution metrics. The Chinese government argues that incomplete or outdated datasets distort its actual food security achievements and economic progress.

- Bangladesh: The Bangladeshi government has raised concerns over data reliability, particularly for indicators like stunting and wasting. It argues that the GHI overlooks significant progress made through programs like the Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) and the National Nutrition Services, leading to an inaccurate portrayal of its hunger situation.

- India: The Indian government has criticized the GHI for using flawed methodologies, particularly its reliance on subjective indicators like Prevalence of Undernourishment (PoU) and Child Mortality. It argues that these do not capture the effectiveness of its large-scale food security programs such as the Public Distribution System (PDS) and the National Food Security Act (NFSA).

- Ethiopia: Ethiopian authorities argue that the GHI does not consider the country’s post-conflict recovery and its impact on food security. They claim the index overlooks how conflict and displacement affect hunger, thereby failing to reflect progress in these areas.

- Vietnam: Vietnam has criticized the GHI for ignoring its significant agricultural advancements and economic growth. Officials argue that the index fails to account for improved food availability and access through modern farming techniques and government policies aimed at reducing poverty and hunger.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) plays a vital role in highlighting food insecurity worldwide, yet this investigative report by IJ-Reportika uncovers critical flaws in its methodology. Issues such as reliance on outdated data, inconsistent metrics, and oversimplification undermine its credibility. The findings reveal how such shortcomings misrepresent nations’ progress and obscure deeper systemic issues, like food distribution inequities and the impact of climate change. By addressing these gaps with greater transparency, updated data sources, and a more holistic approach, the GHI can transform into a robust tool for driving meaningful progress in the fight against global hunger.