Classical performing artist Shohret Tursun said he realized early on that his native Uyghur culture was on the brink of obliteration in Xinjiang, as he watched in horror as fellow musicians and other Uyghur friends were detained or disappeared by Chinese authorities starting in 2017.

From exile in Australia, Tursun did his best to counter China’s efforts to wipe away Uyghur culture by creating artistic works that governmental policies could not destroy.

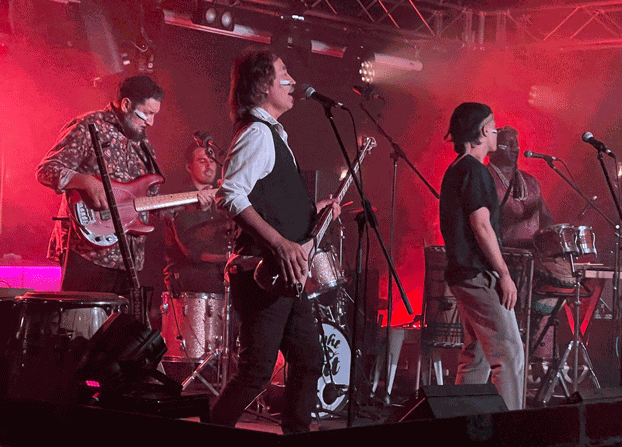

On Sept. 2, 2018, he raised the curtains on the Twelve Muqam Festival at Sydney’s Riverside Theatre, where he performed the “Rak Muqam,” the first suite of the “Twelve Muqam,” a quintessential Uyghur work that includes sung poetry, stories and dancing.

In doing so, Tursun was continuing a musical tradition one thousand years old. Until that day, muqam had never been performed on a major stage in Australia.

Tursun is among a group of Uyghur artists, now living in different parts of the world, who are all working to preserve their identity and culture and call greater attention to the plight of their people back home.

A time of unrelenting darkness

Tursun, who plays several instruments, including the Uyghur dutar and sattar, is joined by singer Rahima Mahmut in the U.K. and artist Gulnaz Tursun (no relation to Shohret Tursun) in Kazakhstan in using art to push back against a sense of hopelessness that pervades the Uyghur exile community.

The three expressed similar sentiments about the purpose of their works during interviews with RFA, saying it was their duty to instill hope and confidence in Uyghurs through their artistic performances and creations.

Shohret Tursun, who has lived in Australia since 1999, said he’s dedicating his life to preserving and disseminating the cultural relics like the “Twelve Muqam,” which is a symbol of the Uyghur nation. He has played in Australia, Japan and in other countries. The performance of his Australian Uyghur Muqam Ensemble in Sydney on July 20, 2019, was streamlined by Uyghurs around the world.

Mahmut sings mournful melodies of Xinjiang to give voice to the Uyghurs unable to speak out. And Gulnaz Tursun creates works of art on canvas to inspire Uyghur teenagers to hope for a better future at a time of unrelenting darkness.

Since 2017, Chinese authorities have detained an estimated 1.8 million of Uyghurs and other native Turkic peoples in a vast network of internment camps for “re-education,” while others outside the prison and camp systems live under constant high-tech surveillance and monitoring.

“The Chinese Communist Party has covered our homeland in blood,” Shohret Tursun said in a speech during the opening ceremony of the Muqam Ensemble.

“China is oppressing us to an unprecedented level, restricting our religion, banning our language, devastating our culture and arts. They are murdering our Uyghur artists. Today, we have done everything we can to found the Australia Uyghur Muqam Ensemble as a way of honoring our ancestors and paving a new path for our descendants.”

Tursun told RFA that he hopes to inspire a new generation of Uyghur performing artists around the world to carry on the torch of Uyghur musical and singing traditions.

‘Music is a tool’

In addition to being a performing artist, Rahima Mahmut is the U.K. representative of the World Uyghur Congress and an advisor to the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China, an international, cross-party alliance of legislators and parliamentarians working to combat the rise of authoritarian China.

For the past 20 years, Mahmut has been using her artistic talent to make the Uyghur voice known through music, while drawing the attention of the international community to the crisis in Xinjiang.

“There is no place that is like a person’s home,” she said. “You cannot compare [home] to anything else. It has been five years since my contact with my family was cut off. Now I can’t even remember the faces of the people I love most, but music is a tool that allows me to turn suffering into strength.”

Mahmut said she always loved to sing but she majored in petrochemical engineering at Dalian University of Technology near China’s Pacific Coast. As she searched for a job after graduation, she experienced firsthand the unequal treatment of Uyghurs at the hands of Chinese state institutions.

She planned to work in Urumqi (in Chinese, Wulumuqi), but she could not get a job there due to severe state discrimination against Uyghurs. She also could not find an acceptable job offer in her hometown of Ghulja (Yining).

But it was the massacre of Uyghur youth in Ghulja, where she had been born and raised, on Feb. 5, 1997, that drove her decision to leave Xinjiang for the U.K.

“The hope for the preservation of our people, the preservation and flourishing of our culture and history, and the future existence of our homeland, can be a reality if we fight for these ideals in our lifetimes,” Mahmut told RFA. “This is why I always say that hopelessness is of the devil. We must be hopeful. Our arts provide us with hope.”

“There is a proverb among our people: Despair is the work of the devil!” she said. “Our art also gives us hope, so I have tried to give hope and confidence to our people during these times of tribulation through art and performance.”

Mahmut, who has lived in the U.K. since 2000, has performed Uyghur songs at major concerts and cultural festivals in the U.K. and across Europe and the United States.

She’s says her life as an activist began on her first day in the U.K., when she explained the Uyghur persecution to her taxi driver.

Symbolic songs

Today, Mahmut speaks about the Uyghur genocide with U.K. government officials, members of Parliament, representatives from Jewish, Muslim and Christian institutions, major U.K. universities, media organizations such as the BBC and Al Jazeera, and documentary filmmakers.

She has also worked as an interpreter at the Uyghur Tribunal in London, which issued a nonbinding determination on Dec. 9, 2021, that China was committing genocide against the Uyghurs and other Turkic people in Xinjiang.

Mahmut said her urgency to showcase the beauty of Uyghur art and music to the world intensified in 2017 when the Chinese government forced assimilation campaign began in earnest.

In addition to performing on stage in the Uyghur language, Mahmud also translated the powerful messages within Uyghur songs, explaining for instance the significance of grief expressed in the lyrics.

She said she recently released a recording of the Uyghur folk song “Lewen Yarlar” (Beautiful Lovers) to remind her audience of the suffering Uyghurs are experiencing and the persistence of their love for their homeland.

The song describes the lives of Uyghur refugees after they fled communist Chinese aggression and oppression.

“‘Lewen Yarlar’ is one such symbolic song,” Mahmut said. “The lyrics go: ‘We found a place in the mountains, finding none in the garden, refusing to bow to the enemy.’”

One of the most powerful songs Mahmut often sings during her performances is “Yearn for Freedom.” The song was adopted from a poem by the late Uyghur poet, writer and political thinker Abdurehim Otkur (1923-1995), a towering figure in modern Uyghur history whose ideas on struggling for national freedom still reverberate among the Uyghur people.

Otkur expressed the Uyghurs longing for freedom:

Neither have I patience, nor forbearance,

A boiling pot is now my beating heart,

An erupting volcano is my heart’s desire

From that volcano I yearn for freedom.

The Uyghur spirit

Visual artist Gulnaz Tursun, who was born into a Uyghur family of intellectuals in the village of Bayseyit in Almaty, Kazakhstan, said she also wants to instill confidence in young Uyghurs through her artistic creations and to encourage them to have faith in the future.

“Believe, the dawn of freedom shall arrive!” Gulnaz Tursun said when asked about the message she wants her paintings to convey to Uyghurs.

“I want to give our children the confidence that we are not helpless, that the Uyghurs are also a great people who have built powerful empires in history, and that the Uyghurs will be able to overcome these difficult times and have a future of freedom,” she said.

After graduating from a Uyghur high school in her village, Gulnaz Tursan attended the Ural Tansykbayev Institute of Crafts and Arts in Almaty in 2002 and was admitted the same year to the Faculty of Design of the Kazakh Academy of Architects and Construction. She graduated with honors and embarked on a career in the art world, participating in many exhibitions of the works of young artists.

Speaking about the impact of the Uyghur genocide on her work, she said the darkness that has befallen Uyghurs in Xinjiang prompted her to shift her style to one that seeks to inspire optimism and confidence in Uyghurs’ future.

In the process, she said, she has created and distributed a number of inspirational digital works on social media, including “Hope,” “Don’t Forget Your Identity,” “Spring,” “The Cute Child of My Motherland’s Free Future” and “Unity.”

With her painting “Spring,” for instance, Tursun said she wants to convey the powerful message that dark clouds from the sky will disappear, and blue sky will arrive.

“Our birds will fly high and free again. Our fruit trees will blossom again. And we shall enjoy the fruits of freedom again,” she said.

Tursun’s previous artistic creations depicted daily Uyghur life, such as woman fetching water or having a conversation over tea. But since 2017, her paintings have mostly been about “inspiring and motivating the young people to have faith for a bright future by reminding them the glorious history of our nation,” she said.

“In order to have positive impact on our young generation, every good thing starts with confidence, so I made designs with confidence-boosting slogans like ‘Have Faith, the Dawn of Freedom Shall Arrive,’” she said.

“I created these artworks to instill confidence in our freedom for the future generation,” she said. “These artworks I created are all based on Uyghur spirit and Uyghur characteristics.”

Translated by RFA’s Uyghur Service. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin.