Lékim Ibragimov was well into his career as an artist when he visited the Kizil Thousand-Buddha Caves in Xinjiang in the 1990s.

It was a seminal experience that would shape his already renowned work and earn him a special commendation at one of the most prestigious exhibitions for contemporary art, the Florence Biennale in Florence, Italy.

The series of rock-cut grottoes, each containing murals of Buddha, sometimes surrounded by other figures, date from the 5th to 14th century and sit on cliffs near Kizil township in Aksu prefecture.

The caves, reputed to contain the most beautiful murals in Central Asia, were an important medium for Buddhist art at a time when Buddhism prevailed in Xinjiang for more than a thousand years until it was replaced by Islam around the 13th century.

Now they are a source of pride and symbol of desired freedom for Uyghurs who live in the region and abroad.

Ibragimov, a Uyghur graphic artist and painter who lives in Uzbekistan, explored the regional capital Urumqi and the town of Turpan. But when he went to the caves, the ancient murals and their historical richness deeply moved him.

“I was particularly inspired by the Kizil Thousand-Buddha Caves [near] Kucha,” he told Radio Free Asia. “These paintings can’t be found anywhere else in the Turkic world. They are the epitome of Uyghur paintings, encapsulating the history and art of the Uyghurs. I found myself captivated.”

Now 78, Ibragimov said he has dedicated more than 40 years to studying the cave murals and incorporating their style into his work.

“Over the years, I introduced these artworks to the world with support from prominent artists who encouraged me to continue,” he said. “Through art, I paved a way for the Uyghur people. I became an academic in Russia, a national-level artist in Uzbekistan, and received many awards. I am delighted to have made this artistic contribution for the Uyghur community.”

Cave frescoes

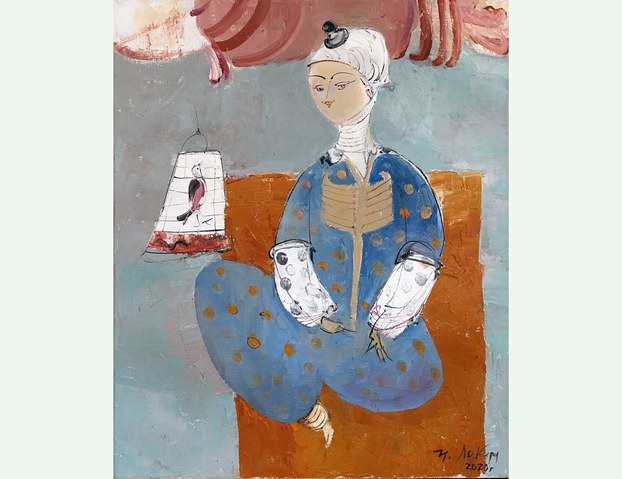

Lékim Ibrahim Hakimoghli, as the artist is known among Uyghurs, has incorporated the style and colors of the cave frescoes into his abstract, surreal artwork that combines drawing, painting and calligraphy.

His paintings earned him widespread recognition in Russia, Germany and other European countries after the 1990s as well as numerous awards, including the special commendation in the painting category at this year’s Florence Biennale, an event that has been held every two years since 1997.

The five pieces Ibragimov presented at the exhibition were among 1,500 works by over 600 artists from 85 countries at the Oct. 14-22 event. Three of his works were of Turkic figures, outlined and accented by muted colors against a light brown background in the style of the frescoes at the Kizil, also known as Bezeklik, Thousand-Buddha Caves.

Another one depicting a neighing steed trying to break free of its tether resembles a Chinese ink-and-water painting, while his rendering of an ancestral angel is reminiscent of the style and motifs of Belarussian-French artist Marc Chagall. All the works were created between 2008 and 2020.

Piero Celona, the vice president and founder of the Florence Biennale, who is knowledgeable about the cave paintings in Xinjiang, expressed admiration for Ibragimov’s work.

“Germany and other European countries have preserved and respected Uyghur culture, and he noticed the similarities [to the cave murals] in my paintings,” Ibragimov told RFA. “He commended my work and emphasized the Uyghur people’s yearning for freedom, predicting a brighter future for them.”

Chinese suppression

The award comes as the Chinese government is repressing Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples living in Xinjiang and trying to Sinicize the vast northwestern region in part by destroying Uyghur culture.

Beijing has denied committing severe human rights violations in the region, despite credible reports, witness accounts and growing condemnation by Uyghur advocacy groups and the international community.

Marwayit Hapiz, a Uyghur painter who lives in Germany and is well-acquainted with Ibragimov’s works, said the inclusion of his paintings in the Florence Biannale was a significant achievement for Uyghur art.

“Lékim Ibrahim’s selections for this exhibition were a rare distinction among Turkic ethnicities,” she told RFA. “He is the sole Turkic artist to have earned this recognition.”

Hapiz, who first met Ibragimov in Urumqi in 1991, calls him one of the leading artists in the field of contemporary Uyghur fine art, whose works in the style of the cave murals highlight the traditional art of Uyghurs.

“I wouldn’t hesitate to call him the foremost artist in Uyghur arts,” Hapiz said. “In Europe, whenever someone inquires about painters of symbolic Silk Road paintings, his name comes up.”

“Lékim Ibrahim’s paintings emanate the spirit of Uyghur art from the era of the Uyghur Buddhas,” she said. “Our Uyghur artistic legacy essentially originates from these stone wall paintings.”

Narratives

Through extensive research, Ibragimov developed a deep understanding of the narratives and tales depicted in the cave wall paintings and incorporated them into his creative spirit, Hapiz said.

“He innovatively adapted their expression and aesthetics, establishing a unique method of painting,” she said.

Ibragimov has played a pivotal role in introducing Uyghur art to the world, alongside other renowned Uyghur painters Ghazi Ehmet and Abdukirim Nesirdin, she added.

“He stands as a distinctive artist from the Silk Road and Asia primarily due to his ability to reflect the ancient paintings,” said Hapiz.

Other artists familiar with Ibragimov’s work took to social media to offer their congratulations and praise.

Gulnaz Tursun, a Uyghur artist from Central Asia, who like Ibragimov, serves as a mentor to young Uyghur artists, told RFA that he “has breathed life back into ancient painting styles.”

Ibragimov played a crucial role in organizing an exhibition of the works of Uyghur artists titled “Heritage,” which took place in the Uzbek capital Tashkent, where he lives, in early October, said Tursun, whose works were displayed at the event.

Thirty artists from eight countries participated, exhibiting more than 100 pieces.

“When I visited Uzbekistan in May, I shared my ideas with [Ibragimov], and he was incredibly supportive and encouraging, and offered his assistance,” she said. “He told me not to be afraid and continued to provide encouragement.”

The exhibition was co-sponsored by Kazakh and Uzbek Uyghur cultural centers.

Artists from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia, the United States, Germany, and other nations participated. Hapiz said she was awarded a gold medal by the Kazakhstan Uyghur culture center, which served as a great source of motivation.

Studied graphic art

Ibragimov, a member of the Academy of Arts of Uzbekistan and an honorary member of the Russian Academy of Arts, was born into a family of teachers in the village of Maly Dekhan in the Uyghur district of Kazakhstan’s Almaty region. His upbringing focused on art and education.

He spent many years in Moscow and studied at the Art College of Nikolai Gogol in Almaty from 1964-1971. He then studied graphic arts at the Tashkent Theater and Arts Institute and began gaining recognition for his artwork across the Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union and in some European countries by participating in domestic and foreign exhibitions.

Ibragimov later lived in Luxembourg for 15 years and traveled to Germany, the Netherlands, Paris, Japan, South Korea and China, where he participated in numerous exhibitions.

In 2012, he completed a decade-in-the-making mega-painting based on “One Thousand and One Nights,” a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales.

The work titled “One Thousand Angels and One Painting” was painted on a 26-foot-high and 217-foot-long canvas. At the time, the work’s grandeur earned it a listing in the Guinness World Records as the world’s largest oil painting.

Ibragimov used three tons of oil paint, 20-30 kilometers (12-19 miles) of wire, and metal and bricks to create the artwork in the style of the cave murals. It features 1,000 angles and depicts the lives of ancient Uyghurs along with elements from Christianity and Buddhism.

“Through the Uyghur painting, I aimed to symbolize unity and harmony among different religions,” Ibragimov said.

Today, Ibragimov’s works can be found in art museums in Uzbekistan, Russia, Hungary, and Kazakhstan, as well as in private collections around the world.

Translated by RFA Uyghur. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.