Commerce in North Korea’s once bustling marketplaces has slowed to a trickle thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, raising questions about the long-term prospects for Kim Jong Un’s experimental effort to give citizens a bit more economic freedom.

Marketplaces, called jangmadang in Korean, had dramatically expanded under the watchful eye of the North Korean dictator, who has sought to kick start the beginnings of a market economy in the communist country. But those plans took a hit when Beijing and Pyongyang closed the Sino-Korean border and suspended all trade in January 2020 in response to the pandemic. The lack of imported goods to trade meant fewer things to sell at markets.

The border closure has devastated the country’s economy, which had already suffered under international sanctions aimed at depriving Pyongyang of resources it could funnel into nuclear and missile programs.

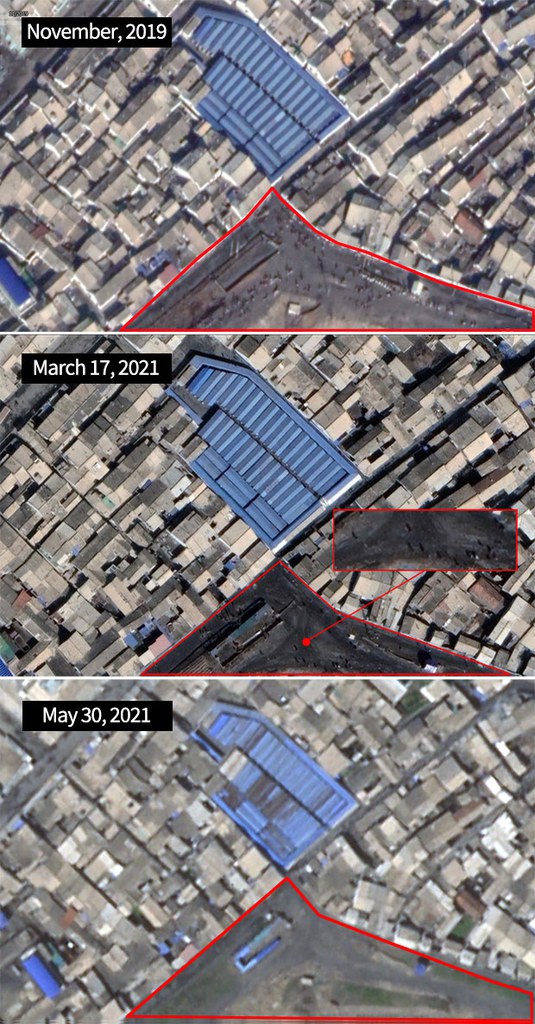

While a resumption of rail freight with China earlier this year had brought on hopes of recovery, the “maximum emergency” declared by Pyongyang after officials announced that the virus was spreading among participants of a massive April military parade killed activity at the markets altogether, satellite images show.

Jacob Bogle, curator of the Access DPRK blog, which uses satellite imagery in its analysis of North Korea, told RFA’s Korean Service that the markets have seen a massive downturn since the pandemic.

According to Bogle, an analysis of satellite images shows that there are at least 477 markets in North Korea, of which 457 are official markets recognized by North Korean authorities.

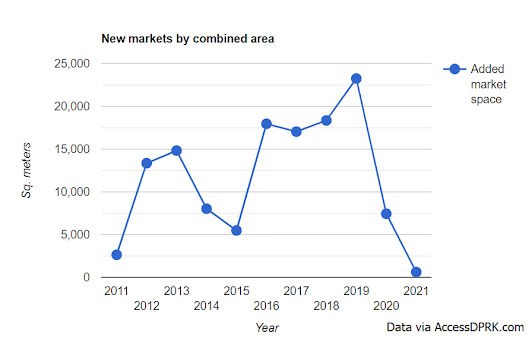

Markets have continued to grow in North Korea since Kim Jong Un came to power. At least 39 markets have opened and 114 markets have expanded since 2011, Bogle said.

But the growth stopped once the pandemic hit, he said.

“In 2019, there was over 23,000 square meters of new market space built around the country. By 2021, it was only 630 square meters of new space,” Bogle said.

“I think there’s a clear connection with market activity and the impacts of COVID and shutting down trade that it greatly impacted the economy,” he said.

The import ban had its biggest impact on those markets near the border, Joung Eunlee of the Seoul-based Korea Institute for National Unification told RFA.

“It seems that the market has contracted more because supply has decreased a lot due to the COVID-19 situation, “ Joung said.

The border closure did not completely kill off the markets, though. Most were able to continue in some capacity with domestically made products.

The coronavirus outbreak has taken a “decisive blow” on the North Korean economy, Lim Eul Chul, a professor at the Institute for Far Eastern Studies at Kyungnam University in South Korea’s southeast.

“Mobility must be guaranteed for a market to a certain extent, but since mobility is not guaranteed, the market inevitably shrinks. Second, raw materials, fuel, and various subsidiary materials must be smoothly supplied from China,” Lim said.

“Without these, market activities shrink. North Korea under COVID-19 is in an environment that is difficult to control. The situation itself can only result in a shrinking market,” he said.

The apparent end of the emerging free market in North Korea may be permanent, Jiro Ishimaru, the founder and editor-in-chief of the Osaka-based Asia Press news outlet that specializes in North Korea, told RFA.

“At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, controls rapidly tightened. First of all, they continued to put pressure on food sales, and gradually introduced a system to sell food through state-run food vendors,” he said.

“It was then that people started saying that they felt like the era of free trade and free economic activity in the market is coming to an end,” Ishimaru said.

Ishimaru said that the state could be using the pandemic to assert more control over the economy and the people.

At the 8th Party Congress in January 2021, Kim Jong Un emphasized that the country and the people would have to get through the pandemic and its accompanying economic crisis through strict adherence to the principle of self-reliance, harkening to the country’s founding Juche ideology.

Lim said this was the beginning of the state exerting more control on the market.

“The national self-reliance is a more orderly self-reliance, that is, the market will also be led by the state. It aims for marketization that is managed and led by the state. As a result, the market is bound to contract,” he said.

Even with a market contraction and policy changes, North Koreans still want to conduct business, a North Korean refugee who now lives in Seoul, identified by the pseudonym Kim Hye Young, told RFA.

Kim was a trade worker in North Korea prior to her escape. She says that a middle class used to higher living standards has developed in the country.

“The demographic composition of North Korea has also changed to favor the jangmadang generation,” she said, referring to the generation that came of age after the marketplaces had become entrenched — in other words, millennials.

“The younger generations are doing things that once could only be done by the rich. They earn money, they live well, and they are exposed to foreign things. I think the standard of living has risen so high that they won’t simply forget the material abundance they experienced,” said Kim.

Kim said that the government may try to crack down on the people’s business activities but will not succeed.

“They can’t be stopped. People will keep longing for the good times and they will be more willing to do anything to get them back,” she said.

Giving North Koreans greater financial autonomy has helped the state too.

North Koreans earn 75% of their income from market activities, while the regime collects about $59 million in market rent annually, the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies reported in 2018.

But even without the pressures of the pandemic, the growth rate of the marketplaces was likely unsustainable.

“If we divide the 10 years of the Kim Jong Un regime into the first half and the second half, the market increased a lot in the first half, but not so much in the second half,” said Joung.

“It seems that there is not enough demand for the market to expand further. There were already so many before the coronavirus pandemic, and the market — for markets — is saturated. In addition, as time goes on … department stores and grocery markets have been created. From that perspective, I think there will be more structural reforms and changes after the coronavirus pandemic,” Joung said.

Translated by Leejin J. Chung. Written in English by Eugene Whong.