Meta’s oversight board on Thursday ordered the removal of a video posted on Facebook by Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen in which he threatened violence against his political opponents and called for an immediate suspension of his accounts.

The ruling, reversing a previous decision, marks the first time the oversight board has instructed Meta to shut down an account run by a government leader, and suggests that the company may be shifting its stance on how it deals with content posted by users who have otherwise enjoyed impunity in what they say on its site.

Hun Sen didn’t immediately comment on the ruling, but called on his social media followers to switch to rival platforms TikTok or Telegram.

The Cambodian leader, who has ruled the country since 1985, has regularly taken to social media to deliver lengthy tirades against his opponents, warning them of consequences if they defy him. Such threats are often acted on by judicial authorities, security forces, and supporters of his ruling Cambodian People’s Party, or CPP.

On Thursday, Meta’s oversight board of independent experts said that in one such speech, live streamed to Facebook in January, Hun Sen ranted about claims that the CPP had stolen votes in prior elections, offering his accusers the choice of “legal action or a club.”

He warned that he would send thugs to beat them up or arrest them in the middle of the night.

While he did not name the target of his ire, Hun Sen’s “stolen votes” comment was widely viewed as a reference to opposition Candlelight Party Vice President Son Chhay, who was convicted of defamation last year after saying that local commune elections in Cambodia had been marred by irregularities.

Intimidating opponents

Cambodia is preparing to hold a general election on July 23, but observers say that the ballot is likely to be neither free nor fair.

Meta initially reviewed the speech after receiving complaints that it violated Facebook’s guidelines on inciting violence, but decided to leave the content up because of its news value.

However, the company referred the content to its oversight board, saying it had created “tension between our values of safety and voice.”

On further review, the board found that the content had indeed run afoul of Facebook’s guidelines prohibiting incitement, citing “the severity of the violation, Hun Sen’s history of committing human rights violations and intimidating political opponents, as well as his strategic use of social media to amplify such threats.”

The board ordered that the video be removed, and called on Meta to suspend Hun Sen’s Facebook and Instagram accounts for six months.

While the call for the account suspension is non-binding, Meta is obligated to take down the video and issue a statement to the public on its reasons for doing so within 60 days.

‘Finally called out’

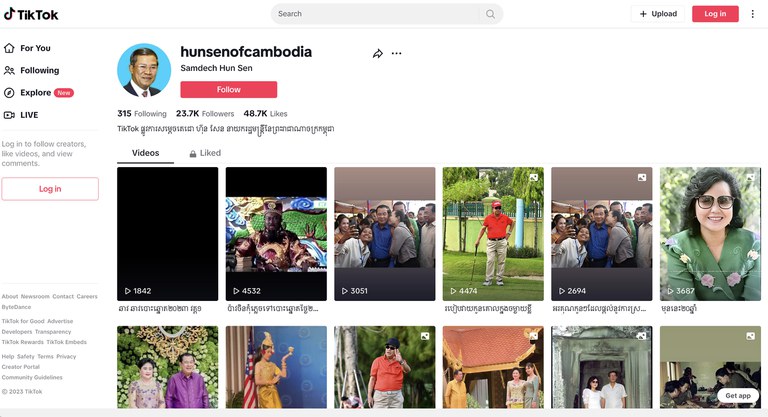

Hun Sen has yet to comment on the oversight board’s ruling, but on Thursday, he posted a message to his Facebook page calling on his 14 million followers to switch to the Chinese video platform TikTok for future updates. Hun Sen’s TikTok account, set up on Wednesday, currently has nearly 22,000 followers.

Later, the prime minister wrote on the Dubai-based Telegram messaging app that he had found Telegram “more useful than Facebook” and told his 85,000 followers on the app that he will be posting content there going forward.

“This will allow me to easily communicate with people while I am traveling to countries where Facebook is not permitted,” he said. “I will keep my Facebook account but I will suspend using it so that people can get information from me through Telegram.”

Hun Sen said his newly created TikTok account would allow him “to more easily connect with the youth.”

‘The stakes are high’

Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director for New York-based Human Rights Watch, issued a statement on Thursday dismissing Hun Sen’s reason for leaving Facebook.

“Hun Sen is finally being called out for using social media to incite violence against his opponents, and he apparently doesn’t like it one bit,” he said.

“That’s the real story about why he’s running away from Facebook, which dared to hold him accountable to their community standards, and into the arms of Telegram, the favored social media messaging system of despots ranging from Russia to Myanmar.”

Robertson said it was high time for tech companies such as Meta to confront world leaders who violate human rights on their platforms.

“The stakes are high because plenty of real world harm is caused when an authoritarian uses social media to incite violence — as we have already seen far too many times in Cambodia,” he said.

Translated by Samean Yun. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.