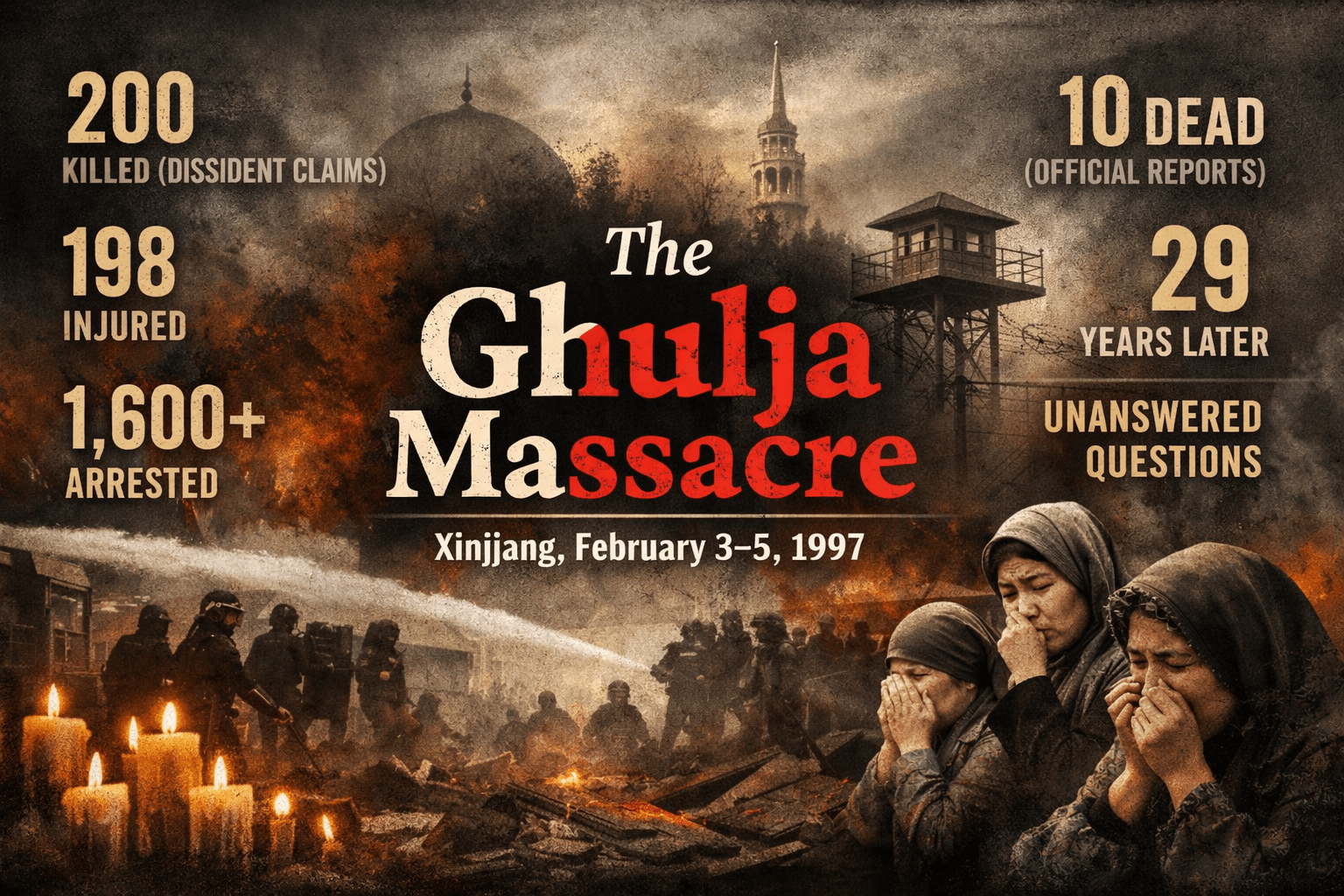

In May 2022, a Japanese-style anime girl started appearing in advertisements shown on Taiwan’s MRT subway network.

Green-eyed, pink-haired with buns and bangs, Momosuze Nene, sprints away from the viewer’s gaze, heading towards “millions of subscribers” on her YouTube channel.

Fans of Nene can sign on to a special website to learn more about her, while the ads hope to spread the word among her growing fanbase in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Australia and the U.S., as well as her native Japan.

And there’s one thing that helps this dirndl-miniskirted YouTuber stand out from her crowd of competitors for the time being: she’s not real.

Part of a growing phenomenon of virtual YouTubers (VTubers), Nene is “a girl from another world” who nevertheless plays video games like her contemporaries, commenting and laughing as the game progresses, and chatting in real time with viewers leaving messages at a rate of several a second in the chat window.

She also sings and dances, chats with viewers and reads out their messages. While her shows are in Japanese, her anime persona and upbeat attitude have made her a hit far outside of Japan.

And her expansion is being funded by fans like tattooed Taipei resident Chiu Wei-chun, 31.

“The advertising agency has no faith in us,” Chiu said. “They said the average fan would likely donate between 30,000 and 50,000 Taiwan dollars.”

Pop idol approach

When he went to the bank to pay in his donation in person, the bank teller said taking money on behalf of a virtual character was a first.

“In my 25 years as a teller, I’ve never heard of such a request,” Chiu quoted her as saying.

Many VTubers are the creation of two Japanese companies — Hololive and Rainbow Club — and tend towards a pop idol approach, although virtual hosts are also found in other genres of video, including technology videos.

With an energy similar to that of an actor playing a cartoon character at a theme park, and motion-capture technology similar to that used to generate Gollum in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies, these VTubers are actually played by human actors behind the scenes.

Many VTubers draw heavily from anime, and come in all shapes and sizes, from vampire nurses to mafia bosses to demons and pirate captains, as well as the ubiquitous sexy anime girl.

They can do pretty much anything a real, live YouTuber can do, including singing, playing games, making art and chatting with their audience in real time. Others talk about their favorite comics or play on variety shows, or go to uninhabited islands as a survival stunt.

The idea of a virtual pop idol isn’t a new one in Japan.

Miku Hatsune is a Vocaloid software voicebank developed by Crypton Future Media, represented in live performance by the image of a 15-year-old teenage girl with long, turquoise twintails.

The act has opened for Lady Gaga and performed at Coachella, will soon be getting her own animated series.

The outbreak of COVID-19 has accelerated the development of the industry in Japan, and it has quickly caught on in neighboring Taiwan.

From white-collar dads to high-schoolers

It’s the potential for personal interaction with VTubers that makes them so popular, and they make liberal use of fan sponsorship to take their programming to the next level via the graded, color-coded SuperChat donation function on YouTube.

The highest donations buy fans stickier messages, increasing the likelihood that the host will see the message and interact with the viewer in some way.

The fan base includes white-collar dads to high-schoolers, with some people willing to pay out half their monthly salary on their favorite virtual idol.

Chiu’s first encounter with Nene was in September 2020, since then he has been a dedicated fan.

The biotech production line manager estimates that he spends a good chunk of his monthly disposable income on sponsoring Nene, and wonders aloud if he needs to rein it in somewhat.

“I’m going to be marrying my girlfriend next year, so I need to save a bit more,” he says. “But I will still need to invest some money in Nene, naturally.”

He said he’s drawn to the character for her childish innocence and relaxed attitude.

“Kind of like a daughter; maybe I’m practicing how to spoil my own daughter,” Chiu said.

According to YouTube’s Super Chat sponsorship rankings for the whole of 2021, only one of the top 10 is a real person.

VTubers are mostly female, and mostly broadcast in Japanese, English, Chinese, Indian languages or Korean from a number of countries.

‘Different voices, different genders’

The most popular VTuber in the world today is the English-language VTuber Gawr Gura from Hololive, with more than four million subscribers.

Otaku culture expert Liang Shih-you, says VTubers are popular because they’re so much fun.

“VTubers let you play a completely different self from the get-go, different voices, different genders, anything, so it creates a multitude of possibilities,” Liang said, citing the example of VTuber Uncle Fox, who looks like a girl with fox ears but has the voice of an uncle.

Taiwan has its own emerging VTubers, including Loco Lost, who debuted in June 2021, calling herself a “17-year-old alchemist,” but later mis-typing it as 217 years, winning her the nickname “grandma.”

She said in an interview with The Reporter and RFA’s Mandarin Service that fans often tell her “I’m working while watching Grandma’s show,” or “I’m playing games and watching Grandma.”

In a riff on the ambiguity around her age, she later changed her avatar into a little girl, using a child’s voice for an entire livestream.

Meanwhile, Taiwan VTuber Vox builds the soothing sounds of autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) videos into cooking shows, inviting fans to suggest food to make.

For Liang, the VTuber phenomenon is all about the soundscapes, the minutiae of a person’s tone of voice or form of expression, that has its roots in the Japanese “sound culture” evident from the early days of virtual characters.

In a world racked with the effects of the climate crisis, war, famine and disease, many fans find this kind of vocalized companionship compelling.

“VTubers may have blossomed all over the world and use different languages and live broadcast styles according to the countries they are from,” he said. “But they are the heirs of those Japanese cultural characteristics.”

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.