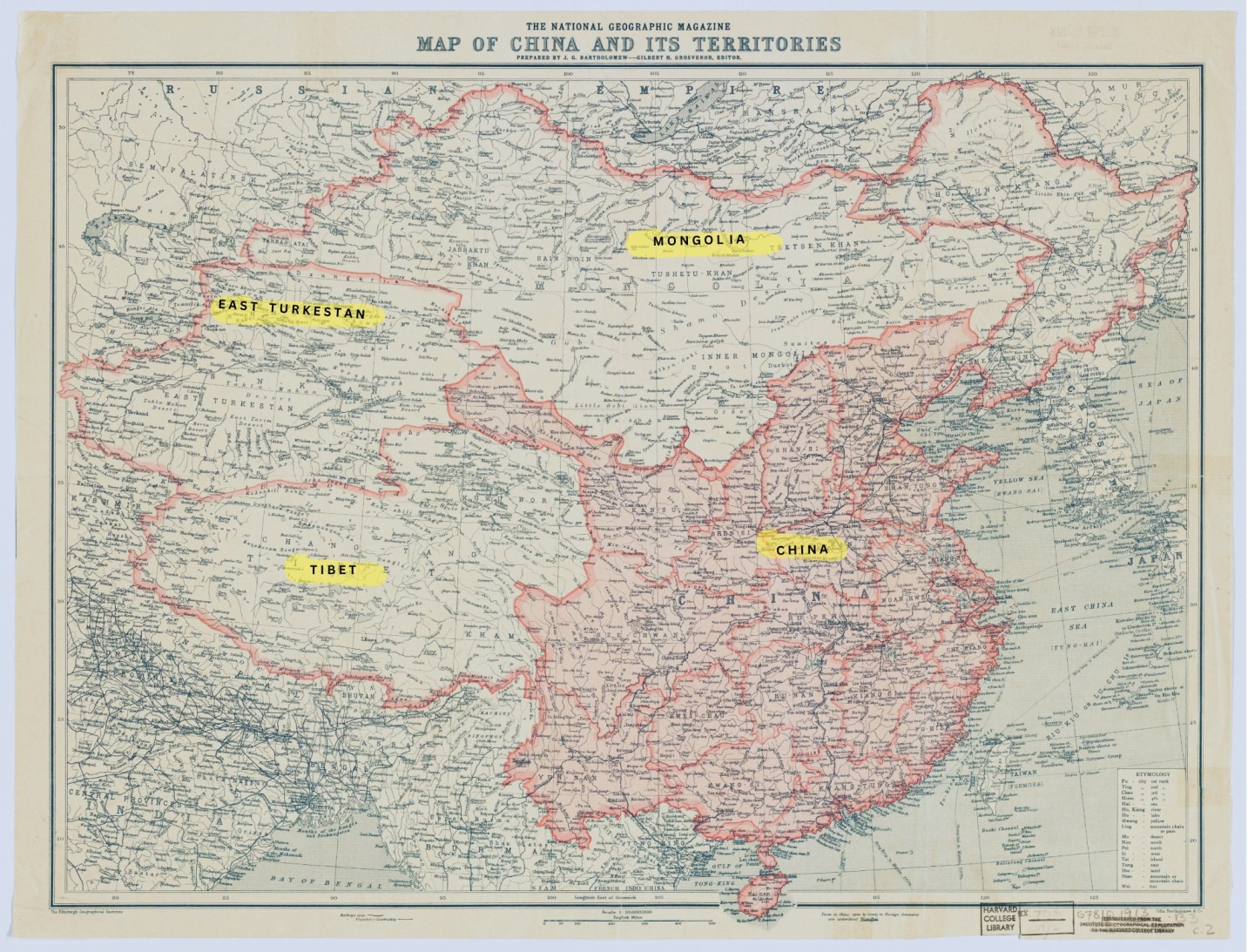

As the People’s Republic of China prepares to mark its National Day on 1 October 2025, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, known to many Uyghurs and diaspora groups as East Turkistan, sits at the center of a geopolitical, human-rights and cultural reckoning. State pages and official ceremonies in Urumqi and other cities present images of unity and development. Outside observers, former detainees and rights groups describe a far different story: mass detention, pervasive surveillance, forced labour and cultural erasure that have reshaped daily life for Turkic Muslim communities in the region. This report compiles available statistics, cultural evidence, and documentary reporting to present a clear-eyed picture.

Quick facts (data points you should know)

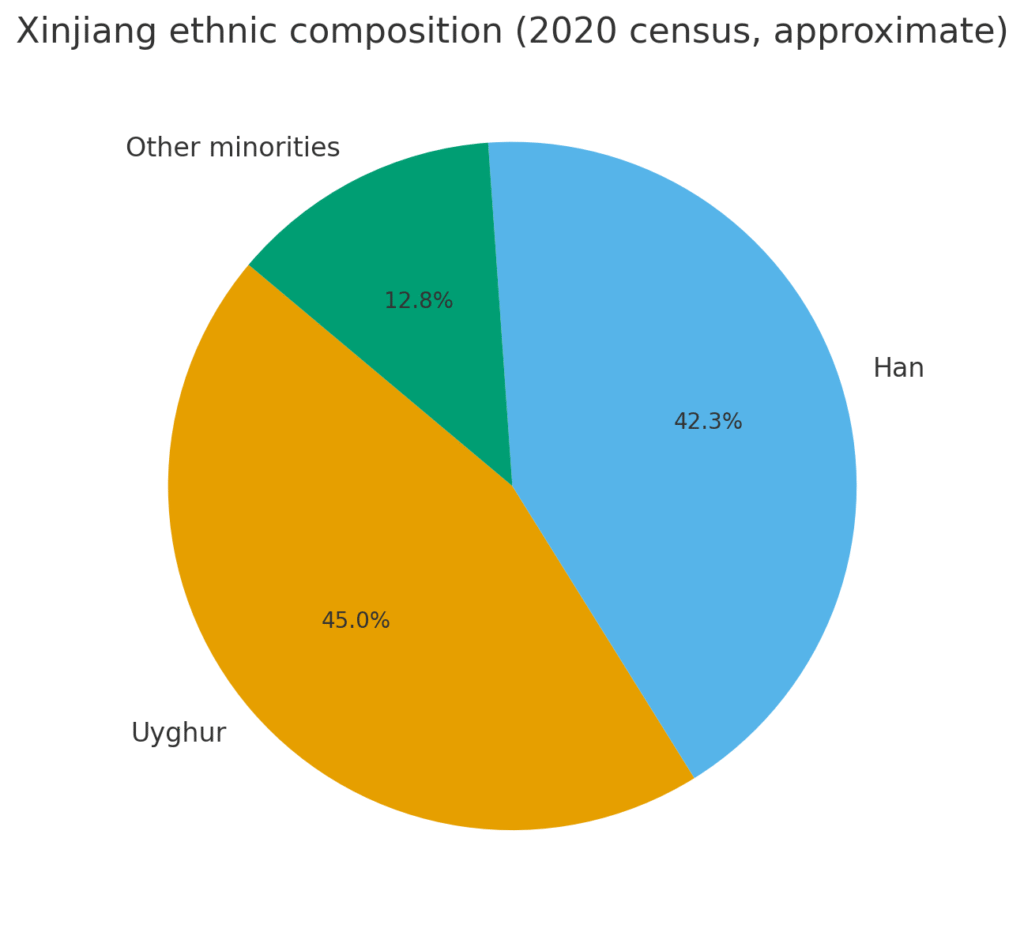

- Xinjiang population (2020 census): ~25.85 million. Ethnic composition (2020 census): Uyghurs ~44.96% (≈11.6 million), Han ~42.24% (≈10.9 million), others ≈12.8%.

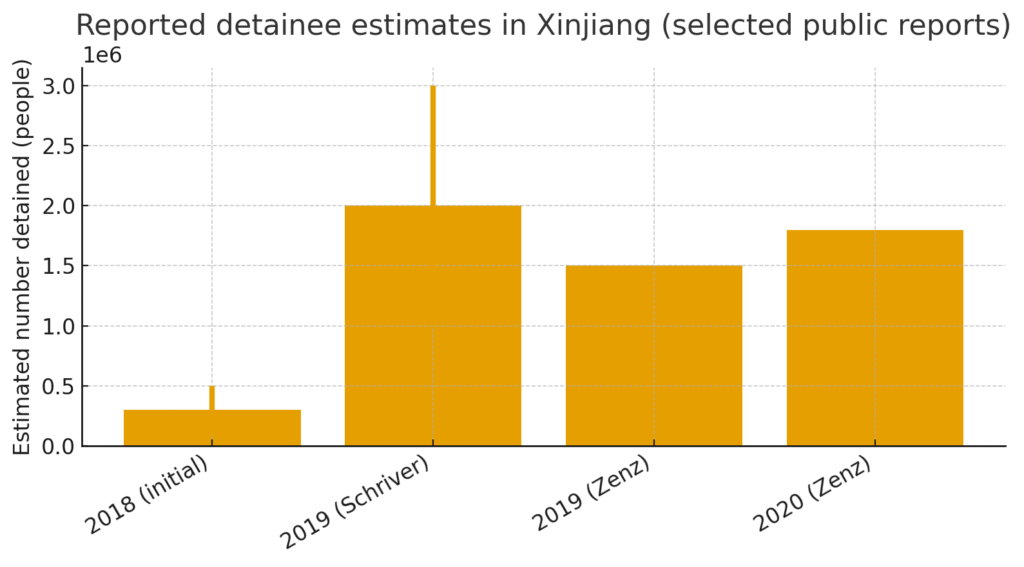

- Reported scale of mass detention (selected public estimates): ranges widely in public reporting, early reports and government documents prompted initial counts in the hundreds of thousands; U.S. officials and researchers later cited figures between 1 million and 3 million; researcher Adrian Zenz’s subsequent analyses put the figure at ~1.5–1.8 million at the high end of many estimates. These figures remain disputed but are widely cited in international reporting.

- Major international findings: Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and UN expert commentary have documented wide-ranging abuses (arbitrary detention, severe restrictions on religious practice and cultural life, forced labour and coercive population-control measures). Some UN and rights reports have described the policies as crimes against humanity in scope and effect.

What “capture” has meant: security measures, detentions and the industrialisation of control

Beginning in earnest from about 2016–2017, Chinese authorities launched what Beijing calls vocational training and deradicalisation programmes. International investigators, rights groups and researchers documented a rapid expansion of internment or “vocational” centers, mass surveillance technology, and heavy policing across Xinjiang. Reports compiled by independent researchers and government commissions documented over a thousand facilities where large numbers of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims were held for periods of “education” and political transformation.

- Scale: Publicly cited estimates vary, a widely reproduced range (used in many government and NGO briefings) places detainees in the hundreds of thousands to several million at the campaign’s peak. Adrian Zenz’s peer-reviewed and policy work is among the most-cited research that estimated up to roughly 1.5–1.8 million detainees at points between 2018 and 2020. U.S. officials and other commentators have cited figures between 1 and 3 million. The opaque nature of Chinese official data and restricted access to researchers means these remain estimates rather than definitive counts.

- Criminal justice vs administrative internment: Chinese authorities framed the centers as part of counter-terrorism and vocational training. Survivors’ testimony and leaked documents reported routines of political study, forced renunciation of Islamic practice, abuse, and, in some cases, transfer into the broader prison or labour system. Human Rights Watch, IJ-Reportika and Amnesty have documented these systemic practices and their long-term social impacts.

- Forced labour and economy: Multiple investigations (governmental and NGO) describe a shift from closed centers to large-scale labour assignment, with Uyghurs incorporated into supply chains, notably in cotton, textiles and some industrial sectors. The U.S. Department of Labor and other agencies have characterised parts of these systems as forced labour and implemented trade and import restrictions as a result.

Cultural losses and the rewriting of heritage

Independent reporting, satellite analyses and regional field research through 2016–2021 documented widespread damage or demolition of religious and historic sites (mosques, shrines and graveyards) and restrictions on religious observance, dress, education in native languages and naming. Analysts called this a campaign of cultural erasure: retooling public space, schooling and the media to privilege an officially defined national narrative and restrict visible markers of Uyghur religious and cultural life. Satellite and on-the-ground reporting in 2018–2020 identified hundreds of religious sites altered, damaged or removed.

Language and education: Uyghur language instruction has been curtailed in some schools through expanded Chinese-medium education policies; bilingual and immersion programmes have been reduced in many parts of the region. Official rhetoric stresses “integration” and Mandarin proficiency; Uyghur and other minority language activists argue the result is erosion of intergenerational transmission of culture.

Life before the crackdown — liturgies, markets, music

Before the 2010s clampdown, East Turkistan’s cities and countryside were defined by vibrant bazaars (Markets), religious life punctuated by daily prayer, weekly markets, weddings and funerary traditions, folk music (the dutar, rawap and muqam traditions), and a language and literary culture stretching back centuries on the Silk Road. That cultural ecosystem – bazaars in Kashgar, the muqam in music houses, mosque communities – was the substrate of Uyghur social life and commerce. Many of those institutions have been weakened by migration, repression, and demographic change.

Life after the capture — surveillance, assimilation, altered public rituals

Post-2017 public life in many parts of Xinjiang shows visible changes: intensified checkpoints, ubiquitous cameras and police checkpoints, apps and QR-based monitoring practices, education campaigns in Mandarin, and official promotion of national holidays and slogans. The region’s public rituals have been reframed to emphasise national unity – placards, staged cultural festivals and “ethnic unity” performances are now common features of state-organised events. These shifts are described in state media as “stability” and “development”; rights groups call them coerced assimilation.

On the eve of National Day 2025: political theatre and international pushback

In late September 2025 President Xi Jinping visited Xinjiang and publicly emphasized “stability” and economic development while marking the region’s 70th anniversary as an administrative entity – a potent image for Beijing as it prepares for National Day. Internationally, the visit and accompanying white papers and state events have been met with denunciations from Uyghur rights groups, statements from NGOs and renewed calls for independent access and accountability.

What the statistics tell us — and what they hide

The charts we include with this article visualise two critical datasets:

- Reported detainee estimates: public reporting contains wide ranges. This is partly because reporting aggregated different kinds of detentions (temporary administrative re-education; longer incarceration; penal sentences) and because independent verification inside Xinjiang remains extremely limited. The estimates remain important because multiple independent sources, leaked documents, survivor testimony and government budgetary lines converge on a picture of large-scale, state-organised programs of detention and transformation.

- Ethnic composition (2020 census): Uyghurs remain the largest single ethnic group in the region according to the official 2020 census (≈45%), with Han close behind (≈42%), and other minorities making up the rest. Demographic change is itself a contested field: some analyses point to migration, language change and policy-driven education and family-planning measures as forces changing the region’s social fabric. These are matters of both policy and human consequence.

Cultural resilience and the human stories that numbers obscure

Numbers and satellite images cannot fully capture the personal damage — the families cut off from relatives, children placed in state boarding schools away from parents, the loss of imams, singers and local scholars to detention or exile. Survivors’ testimonies describe daily practices of enforced political study, pressure to abandon religious life, and the emotional trauma of indefinite separation. At the same time, diaspora communities continue to keep the language, music and memory alive — a parallel cultural life that resists erasure.

What accountability requires

Investigative journalists, researchers and rights organisations have called for:

- Independent, unfettered access for UN special procedures, humanitarian observers and impartial investigators.

- Transparent release of administrative data on detentions, sentencing, labour assignments and children’s schooling.

- Corporate accountability for supply chains and forced labour risks.

- Legal mechanisms to investigate and, if appropriate, prosecute international crimes where evidence supports such steps.

East Turkistan / Uyghurs — Timeline of Key Events

- c. 744 : Establishment of the Uyghur Khaganate by Turkic groups after rebelling against the Second Turkic Khaganate.

- 840 (circa) : Collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate after Kyrgyz attacks; Uyghur groups migrate south into the Tarim Basin and Gansu regions.

- c. 843 : Foundation of the Kingdom of Qocho / Gaochang in the Tarim Basin by Uyghur settlers.

- 10th century (c. mid-900s) : Karakhanid state strengthens in the region; conversion of Karakhanid elites spreads Islam among Turkic peoples in the Tarim Basin.

- 1209 : Qocho and other Tarim Basin polities come under Mongol rule as the Mongol Empire expands.

- 13th–14th centuries : Rule of Chagatai Khanate and later local polities (e.g., Yarkent Khanate); continued Turkic-Islamic cultural development.

- 1759 : Qing dynasty defeats the Dzungar Khanate and consolidates control over Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin.

- 1865–1877 : Yakub Beg establishes an independent Kashgaria (Yettishar / Kashgar Emirate); Qing forces reconquer the area by the late 1870s.

- 1884 : The Qing government formally reorganises the region and establishes Xinjiang as a province.

- 1911–1928 : After the fall of the Qing, Xinjiang is governed by provincial/rival warlords under nominal Republic of China authority.

- 1928–1933 : Period of political instability and Jin Shuren’s governorship, leading to uprisings.

- 1933 (Nov)–1934 (Apr) : First East Turkestan Republic proclaimed in Kashgar (short-lived Islamic republic).

- 1933–1944 : Sheng Shicai’s rule in Xinjiang — Soviet influence, internal purges, and shifting allegiances.

- 1944 (Nov) : Second East Turkestan (Ili) Republic declared in northern Xinjiang with Soviet backing; existed until 1946.

- 1949 : People’s Republic of China asserts control over Xinjiang; Uyghur independence movements are suppressed.

- 1950s–1960s : PRC campaigns (land reform, collectivisation, restrictions on religion and local elites) reshape governance and economy.

- 1966–1976 : Cultural Revolution era — widespread disruption of religion, traditional culture, and education.

- 1990s–2000s : Recurring unrest and heightened security measures; Uyghur diaspora activism grows abroad.

- 2009 (July) : Urumqi riots — large inter-ethnic violence in the capital; hundreds killed; leads to intensified security measures.

- 2013 : Belt and Road Initiative announced; Xinjiang identified as a strategic land corridor.

- 2014 (May) : Central Work Conference / Xinjiang Work Forum — Beijing emphasises security, ethnic “mingling,” and counter-extremism.

- 2016 (Aug–Sep) : Chen Quanguo appointed Party Secretary of Xinjiang; security infrastructure and policing intensify.

- 2017 : Rapid expansion of internment centres and mass detentions begins.

- 2018 : Leaked internal documents and survivor testimony reveal detention protocols and surveillance systems.

- 2019 : International attention escalates — estimates of hundreds of thousands to millions detained; forced labour exposed.

- 2020 : Research publicises higher detainee estimates and coercive policies; supply-chain investigations intensify.

- 2021 : NGO reports describe widespread abuses as potential crimes against humanity.

- 2022 : UN assessment raises concerns of actions possibly amounting to crimes against humanity.

- 2023 : International advocacy and pressure grow; governments impose trade restrictions and sanctions linked to forced labour.

- 2024 : Reports of continued cultural destruction, language suppression, and assimilationist policies.

- 2025 (Sept) : President Xi Jinping visits Xinjiang ahead of National Day; state media stress “stability and development,” while NGOs renew calls for accountability.