Taking over from the inside: China’s growing reach into local waters

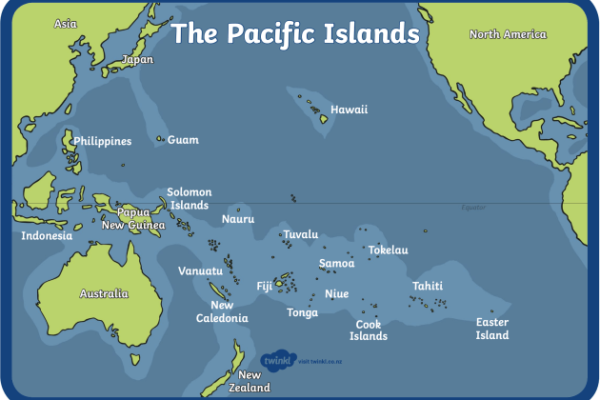

On March 14, 2016, Argentina’s coast guard detected a Chinese vessel fishing illegally in national waters. When the ship attempted to ram the coast-guard cutter, the Argentinians opened fire on the vessel, which soon sank. The Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10 was one of eleven Chinese squid vessels that the Argentine navy has chased for suspected illegal fishing since 2010, according to the government. But one year after the incident, Argentina’s Fishing Council announced that it would grant fishing licenses to two vessels owned by the same Chinese operator that owned the ship the Argentine navy had chased the previous year. These ships would sail under the Argentine flag through a local front company. The decision seemed to violate Argentine regulations that not only forbid foreign-owned ships from flying Argentina’s flag or fishing in its waters but also prohibit granting licenses to operators with records of illegal fishing. The move may have been a contradiction, but it is an increasingly common one around the world. Over the past three decades, China has gained supremacy over global fishing by dominating the high seas with more than 6,000 distant-water ships. When it came to targeting other countries’ fishing grounds, Chinese fishing ships typically sat “on the outside,” in international waters along sea borders, running incursions across the line into domestic waters. In recent years, from South America to Africa to the far Pacific, China has increasingly taken a “softer” approach, gaining control from the inside through legal means by paying to flag in their ships so they can fish in domestic waters without the risk of political clashes, bad press, or sunken vessels. Infographic by The Outlaw Ocean Project This method typically involves going around prohibitions on foreign shipowners by partnering with local residents and giving them majority ownership stakes. Through these partnerships, Chinese companies can register their ships under the flag of another country, gaining permission to fish in that nation’s territorial waters. Sometimes Chinese companies sell or lease their ships to locals but retain control over decisions and profits. In other places, these companies pay fees to gain fishing rights through “access agreements.” From Micronesia to Iran Chinese companies now control nearly 250 flagged-in vessels in the waters of countries including Micronesia, Kenya, Ghana, Senegal, Morocco, and even Iran. Many of these companies have been tied to a variety of fishing crimes. Trade records show that some of the seafood caught on these vessels is exported to countries including the United States, Canada, Italy, and Spain. Mar del Plata is Argentina’s largest fishing port and the headquarters for many fishing companies. Many Argentine-owned fishing vessels have, however, been neglected in recent years. In some parts of Mar del Plata’s port, those vessels now sit neglected or sunken, unused and unsalvageable. (Pete McKenzie/The Outlaw Ocean Project) Most countries require ships to be owned locally to keep profits within the country and make it easier to enforce fishing regulations. “Flagging in” undermines those aims. And aside from the sovereignty and financial concerns, food security and local livelihoods are also undermined by the export of this vital source of affordable protein, often to Western consumers. In the Pacific Ocean, Chinese ships comb the waters of Fiji, the Solomon Islands, and Micronesia, according to a 2022 report by the U.S. Congressional Research Service. “Chinese fleets are active in waters far from China’s shores,” the report warned, “and the growth in their harvests threatens to worsen the already dire depletion in global fisheries.” The tactic of “flagging in” is not unique to the Chinese fleet. American and Icelandic fishing companies have also engaged in the practice. But as China has increased its control over global fishing, Western nations have jumped at the opportunity to focus attention on its misdeeds. Even frequent culprits can also be easy scapegoats. When criticized in the media, China pushes back, not without reason, by dismissing their criticism as politically motivated and by accusing its detractors of hypocrisy. Still, China has a well-documented reputation for violating international fishing laws and standards, intruding on the maritime territory of other countries and abusing its fishing workers. Two local men fish in Mar del Plata, Argentina, in March 2024. (Pete McKenzie/The Outlaw Ocean Project) History of misbehavior In the past six years, more than 50 ships flagged to a dozen different countries but controlled by Chinese companies have engaged in crimes such as illegal fishing and unauthorized transshipments, according to an investigation by the Outlaw Ocean Project. China’s sheer size, ubiquity and history of misbehavior is raising concerns. In Africa, Chinese companies operate flagged-in ships in the national waters of at least nine countries. In the Pacific, an inspection in 2024 by local police and the U.S. Coast Guard found that six Chinese flagged-in ships in the waters of Vanuatu had violated regulations requiring them to record their catch in logbooks. In August 2019, a reporting team inspected a Chinese fishing vessel off the coast of West Africa. (Fábio Nascimento/The Outlaw Ocean Project) China’s control over local resources is not constrained to domestic waters. In Argentina, China has provided billions of dollars in currency swaps, providing an economic lifeline amid domestic inflation and hesitancy from other lenders. China has also made or promised billion-dollar investments in Argentina’s railway system, hydroelectric dams, lithium mines, and solar and wind power plants. This money has bought Beijing the type of influence that intervened in the fate of the crew from the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 10. When the ship sank, most of the crew were scooped up by another Chinese fishing ship and returned to China. However, four of them, including the captain, were brought to shore, put under house arrest and charged with a range of crimes by a local judge who said the officials had endangered their own crew and the coast guard officers who chased them. China’s foreign ministry soon pushed back against the arrest. Three days later, Argentina’s foreign minister told reporters that the charges had “provoked a reaction of great concern…