Category: Americas

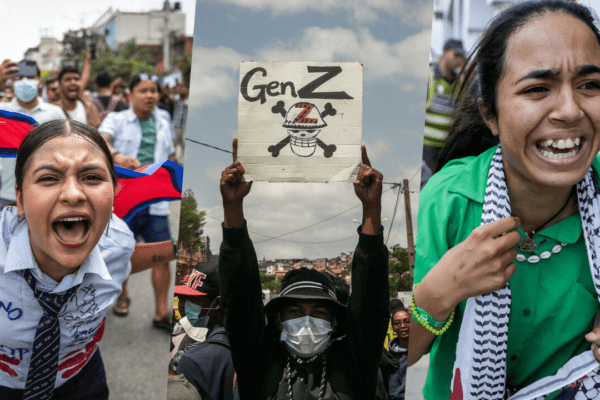

After the Uprising: Tracking Change in the Wake of Gen Z–Led Protests (Survey)

Survey of 10,000 respondents across seven regions examining causes, outcomes and lasting effects of Gen Z–led protests — and the central role of social media.

Rare Earth Metals: The Critical Elements Powering the Modern World

Rare earth metals power EVs, wind turbines & defense tech. Discover what they are, where they’re mined, China’s dominance, and the escalating geopolitical struggle.

Canada Close to Finalising $2.8 Billion Uranium Supply Deal with India

Canada and India are close to finalising a $2.8 billion uranium supply deal to fuel India’s nuclear plants, strengthening civil nuclear cooperation and long-term energy security

Self-Immolation as Students Protest

A Tibetan monk set himself ablaze Wednesday at his monastery in China’s northwestern Qinghai province following protests by several thousand Tibetan students calling for education reforms, sources said. The self-immolation occurred at a monastery in Qinghai’s Rebkong (in Chinese, Tongren) county in Malho (in Chinese, Huangnan) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, triggering protests by hundreds against Chinese rule in Tibetan-populated areas, exile sources said. The burning came a day after nearly 4,000 middle school students held protests demanding Tibetan language and other rights in Rebkong and in neighboring Tsekhog (in Chinese, Zeku) county, sources inside Tibet said. The students had been prevented from leaving their schools, the sources said, with one source adding, “The authorities have detained all the students inside the schools.” Rebkong was the scene of constant student protests in October 2010 against a proposed change in the language of instruction in schools from Tibetan to Chinese. The self-immolation on Wednesday was the 28th by Tibetans since they began a wave of fiery protests in February 2009 to challenge Beijing’s rule and call for the return of Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader the Dalai Lama. Part of the student crowd protesting over language rights in Rebkong county. Chinese security A couple of hours later, hundreds of Tibetans converged at the monastery to protest, drawing Chinese security forces. “Around 11 a.m. or 12 p.m., local Tibetans gathered on the grounds in front of the monastery and raised slogans. They recited prayers for the Dalai Lama and remained firmly at the site,” another Tibetan exile source said. “The local police ordered them not to recite prayers and to disperse, but the crowd refused,” the source said. “The situation is tense.” The latest self-immolation occurred four days after Uprising Day, the politically sensitive March 10 anniversary of the 1959 flight into exile of the Dalai Lama and of regionwide protests throughout Tibet in 2008. The wave of self-immolations prompted a call last week from well-known Tibetan blogger Woeser and senior Tibetan religious leader Arjia Rinpoche to end the fiery protests, saying that Tibetans opposed to Chinese rule should instead “stay alive to struggle and push forward” their goals. Tibet’s India-based exile cabinet marked this year’s March 10 anniversary of the failed 1959 national uprising against Chinese rule with a statement noting what it called China’s efforts over the last half-century “to annihilate the Tibetan people and its culture.” Lobsang Sangay, the head of the exile government, said that while he strongly discourages self-immolations, the “fault lies squarely with the hardline leaders in Beijing.” The Chinese government has blamed the Dalai Lama for the self-immolations, accusing the 76-year-old Buddhist leader and his followers of plotting to create “turmoil” in China’s Tibetan-inhabited areas. But Sangay said “the self-immolations are an emphatic rejection of the empty promises of [China’s] so-called ‘socialist paradise’” and the lack of ability to protest in any other way in Tibet. “Today, there is no space for any conventional protests such as hunger strikes, demonstrations and even peaceful gatherings in Tibet,” Sangay said. “Tibetans are therefore taking extreme actions such as … [committing] self-immolations,” Sangay said. Reported by Lobe Socktsang and Soepa Gyatso for RFA’s Tibetan service. Translated by Karma Dorjee. Written in English by Parameswaran Ponnudurai. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

The Chinese Global Brain Turning Back to Home

The Investigative Journalism Reportika report, “The Chinese Global Brain Turning Back to Home,” examines China’s strategic repatriation of STEM talent to drive innovation in AI, semiconductors, and more. Highlighting initiatives like the Thousand Talents Plan and “Made in China 2025,” it details the return of experts from the U.S., Europe, and beyond, their contributions to China’s tech ecosystem, and the geopolitical tensions, including espionage concerns, reshaping global innovation.

US, South Korea to ‘Move Forward’ on Nuclear-Powered Submarines Amid Major Trade Deal

South Korea secures US approval to build nuclear-powered submarines under a major trade and security deal involving $350bn in investments and reduced tariffs.

Devotion and defiance: Highlights from RFA Tibetan

For nearly three decades, Radio Free Asia has provided critical Tibet coverage, serving as an information lifeline for Tibetan audiences living under China’s authoritarian rule and connecting them to Tibetans in exile – and all the while offering a rare window into life in the highly restricted region. Through shortwave radio and digital platforms, RFA Tibetan has reported epochal moments in the history of modern Tibet. It recorded first-hand accounts of the widespread protests in Tibet in 2008 and the subsequent wave of self-immolations. RFA documented the Dalai Lama’s historic voluntary devolution of his temporal powers in 2011 and transfer of it to the democratically elected leader of Tibet’s exile government, or the Central Tibetan Administration. Audiences in Tibet have secretly accessed RFA broadcasts at great peril to their own lives. They have contended with China’s sophisticated censorship apparatus, deliberate signal jamming, and the risk of prison. A teacher helps a student to write the alphabet in a first-grade class at the Shangri-La Key Boarding School during a media-organized tour in Dabpa county, Kardze Prefecture, Sichuan province, China, Sept. 5, 2023.(Andy Wong/AP) Religious and linguistic persecution in Tibet RFA has meticulously documented China’s systematic efforts to erode Tibetan cultural identity, where children and monks as young as five are being removed from Tibetan-language schools and are forcefully admitted in Chinese boarding schools. RFA journalists have revealed how new educational policies mandating Mandarin as the primary language of instruction have effectively marginalized the Tibetan language in Tibet. RFA has exposed the Chinese government’s intensifying control over Tibetan monasteries through new administrative regulations and forced closures. RFA has detailed China’s efforts to accelerate the Sinicization of Tibetan Buddhism, where monastic education requires “patriotic education” and legal study. Population caps in Buddhist academies such as Larung Gar have forced thousands of monks and nuns to disrobe, and admission criteria now include loyalty tests to the Chinese Communist Party. RFA reports have revealed the government’s strategy of controlling religious institutions from within while publicly claiming religious freedom. Tsezung Kyab, 27, self-immolates on Feb. 25, 2013, at Shitsang Monastery in Luchu region of eastern Tibet.(RFA Tibetan) Beginning in 2009, RFA also documented a wave of self-immolations across Tibet, with the first monk setting himself alight in February 2009, followed by a dramatic escalation after 2011. To date, over 157 self-immolations have been confirmed inside Tibet and in exile communities, with RFA carefully verifying each case. This reporting has preserved the final statements of many self-immolators, revealing their consistent demands for freedom, the return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet, and an end to Chinese repression. These acts of ultimate protest involved Tibetans from all walks of life—monks, nuns, students, nomads, farmers, and parents—ranging from teenagers to people in their 80s, though the majority were young monks between 18-30 years old. During the COVID-19 pandemic, RFA provided rare insights into the situation inside Tibet, reporting on lockdown conditions and government prioritization of political stability over public health. RFA coverage of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, as well as the recent 2025 Dingri earthquake, highlighted both the devastation in Tibetan areas, challenged Chinese government narratives, and shed light on the remarkable community-led voluntary response that outpaced official relief efforts. Video: Former Atsok monastery site completely submergedEnvironmental and human impact of unchecked development RFA’s investigative reporting has exposed the environmental and cultural devastation resulting from China’s aggressive development policies in Tibet, including the submersion of the historic Atsok Monastery due to a dam expansion. RFA also broke the story of the recent Dege protests in 2024, where hundreds demonstrated against the planned construction of a massive dam on the Drichu River that would submerge at least six ancient monasteries and force the relocation of at least two villages. RFA revealed how Chinese authorities arrested hundreds of protesters in February 2024, including monks and local residents, with many facing beatings and interrogation. Video: A timeline of the Dege protests against the proposed dam constructionRFA has revealed the devastating impact of mining on Tibet’s fragile ecosystem and the local communities dependent on these resources. The coverage of China’s massive forced resettlement programs has shown how more than two million Tibetan nomads have been forcibly relocated from their ancestral grasslands into urban settlements, destroying traditional sustainable livelihoods and creating new social problems while clearing land for resource extraction. Video: Tibetans in 26 countries vote for leader of exiled governmentDemocratic government-in-exile RFA has chronicled the remarkable development of Tibetan democracy-in-exile, from the first direct elections of the Kalon Tripa to the most recent 2021 elections for Sikyong – the political leader of the Central Tibetan Administration. Following the Dalai Lama’s devolution of political power in 2011, RFA documented the historic first democratic transfer of leadership to Harvard-educated legal scholar Lobsang Sangay, who served two terms. RFA reporting on the 2021 elections captured the vibrant democratic process that elevated Penpa Tsering to the Sikyong position, highlighting candidate debates, unprecedented voter participation across the global diaspora, and the peaceful transition of power. RFA also provided in-depth reporting on Sino-Tibet talks that sought to negotiate prospects of “genuine” autonomy for Tibet under China as per the Central Tibetan Administration’s Middle Way Approach – which urges greater cultural and religious freedoms guaranteed for ethnic minorities under provisions of China’s constitution. Nine rounds of formal discussions later, the talks ground to a halt in 2010 after China rejected the proposals although there was no call from the Tibetan side for independence. Foreign governments, including the U.S., have urged Beijing to resume dialogue without preconditions. Video: Last surviving CIA officer trained Tibetan fighters at Camp HaleStories of Tibetan resilience, defiance, and hope Throughout it all, RFA has highlighted stories of Tibetan resilience, resistance, and achievement. RFA has profiled artists preserving traditional music despite restrictions on cultural expression; young entrepreneurs building sustainable businesses that honor Tibetan craftsmanship; athletes overcoming political obstacles to compete internationally, and scholars working diligently to digitize ancient texts at risk of being lost forever. RFA’s coverage has celebrated the Tibetan spirit and determination to thrive…

Controversial Zohran Mamdani: Redefine—or Ruin—New York amid uncertain global times

Zohran Mamdani’s socialist rise to New York City’s mayoralty sparks fierce debate. Can his radical promises survive the realities of governance amid Trump’s clash with China and a shifting global order?

RFA suspends remaining editorial operations amid funding uncertainty

Protective measures taken with hope of rebuilding news operations in future WASHINGTON – With the government shutdown and delay in receiving funding for the new fiscal year, effective Oct. 31, Radio Free Asia (RFA) will halt all production of news content for the time being. The move is part of a plan for the Congressionally-funded private corporation to implement cost-saving measures that can help sustain the organization should appropriated funding streams resume. President and CEO Bay Fang issued the following statement: “Because of the fiscal reality and uncertainty about our budgetary future, RFA has been forced to suspend all remaining news content production – for the first time in its 29 years of existence. In an effort to conserve limited resources on hand and preserve the possibility of restarting operations should consistent funding become available, RFA is taking further steps to responsibly shrink its already reduced footprint. “This means initiating a process of closing down overseas bureaus and formally laying off furloughed staff and paying their severance – many of whom have been on unpaid leave since March, when the U.S. Agency for Global Media unlawfully terminated RFA’s Congressionally appropriated grant. “However drastic these measures may seem, they position RFA, a private corporation, for a future in which it would be possible to scale up and resume providing accurate, uncensored news for people living in some of the world’s most closed places.” During its tenure, RFA’s groundbreaking reporting on the Uyghur genocide in Xinjiang, the CCP’s cover-up of COVID-19 fatalities, the unfolding crisis in Myanmar since the 2021coup, Chinese hydropower projects in the Tibetan regions, and the journeys of North Korean defectors has built a public record of transparency in some of the world’s most repressive places, holding autocrats and elites accountable to their people and internationally. Other measures to conserve resources on hand include ending leases of overseas offices and bureaus in Dharamsala, Taipei, Seoul, Istanbul, Bangkok, and Yangon. In the last five years, RFA created new editorial units focused on China’s malign influence in the Indo-Pacific region and globally, investigating PRC secret police stations in the United States and Europe, election interference by the Chinese Communist Party in Taiwan and other Asian countries, and PRC influence operations in Pacific island countries. RFA’s incisive brand of journalism has made it and its journalists a constant target, with its reporters facing pressure and threats since its inaugural report in Mandarin was heard in China on Sept. 29, 1996. Authorities in China, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Cambodia have detained family members, sources, reporters, and contributors. Listeners in North Korea have been severely punished and reportedly executed for accessing RFA’s reports. Nevertheless, RFA’s journalistic operations have until now withstood government intimidation and attacks. In the months since the USAGM illegally terminated its Congressionally appropriated grant to RFA, and despite layoffs and furloughs that diminished editorial staff by more than 90%, the private grantee has continued to fulfill its Congressional mandate to provide accurate, timely news to people living in some of the most closed media environments in Asia thanks to a preliminary injunction issued by the United States Federal District Court for the District of Columbia, which USAGM has appealed. RFA has also continued to win awards for its reporting, including two national Edward R. Murrow awards in August and a Gracie Award in March. While many services, including RFA Uyghur and Tibetan, have already gone dark, others have continued to produce limited output, including RFA Burmese, Khmer, Korean, Mandarin Chinese, and Vietnamese. But these will cease on Oct. 31. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika