Category: Americas

Myanmar Christians, wary of airstrikes, celebrate Christmas in a cave

Many members of Myanmar’s Christian minority celebrated Christmas in fear this year, worried that the military would unleash airstrikes on them, with some worshippers taking to the safety of a cave deep in the forest for Christmas Eve mass. Predominantly Buddhist Myanmar has been engulfed in conflict since the military overthrew an elected government in 2021, with fighting particularly heavy in ethnic minority areas where many Christians live and where generations have battled for self-determination. “Christmas is a very important day for Christians, it’s also important to be safe,” said Ba Nyar, an official in an ethnic minority administration in eastern Myanmar’s Kayah state in an area under the control of anti-junta insurgents. “That’s why lately religious ceremonies have only been held in Mother’s Cave, which is free from the danger of air strikes,” he told Radio Free Asia, referring to a cave in the forest that covers the state’s craggy hills near the border with Thailand. Several hundred people, most of them women and children, crowded into the cave on Christmas Eve, squatting on its hard-packed floor for a service led by a priest standing behind an altar bedecked with flowers and candles. Ba Nyar and other residents of the area declined to reveal the cave’s location, fearing the junta would bomb it with aircraft or attack drones if they knew where it was. Villagers in a cave for Christmas Eve mass in a rebel zone in Myanmar’s Kayah state on Dec. 24, 2024.(Christ the King – Loikaw via Facebook) Most of those attending the service in Mother’s Cave have been displaced by fighting in Kayah state, where junta forces have targeted civilians and their places of worship, insurgents and rights groups say. Nearly 50 villagers were killed in Kayah state’s Moso village on Christmas Eve in 2021, when junta troops attacked after a clash with rebels. In November, the air force bombed a church where displaced people were sheltering near northern Myanmar’s border with China killing nine of them including children. More than 300 religious buildings, including about 100 churches and numerous Buddhist temples, have been destroyed by the military in attacks since the 2021 coup, a spokesman for a shadow government in exile, the National Unity Government, or NUG, said on Tuesday. RFA tried to contact the military spokesman, Major General Zaw Min Tun, for comment but he did not answer phone calls. The junta rejects the accusations by opposition forces and international rights groups that it targets civilians and places of worship. About 6.5% of Myanmar’s 57 million people are Christian, many of them members of ethnic minorities in hilly border areas of Chin, Kachin, Kayah and Kayin states. No Christmas carols In northwestern Myanmar’s Chin state, people fear military retaliation for losses to insurgent forces there in recent days and so have cut back their Christmas festivities. “When the country is free we can do these things again. We just have to be patient, even though we’re sad,” said a resident of the town of Mindat, which recently came under the control of anti-junta forces. “In December in the past, we’d hear young people singing carols, even at midnight, but now we don’t,” said the resident, a woman who declined to be identified for safety reasons. “I miss the things we used to do at Christmas,” she told RFA. In Mon Hla, a largely Christian village in the central Sagaing region, a resident said church services were being kept as brief as possible. Junta forces badly damaged the church in the home village of Myanmar’s most prominent Christian, Cardinal Charles Maung Bo, in an air raid in October. “Everyone going to church is worried that they’re going to get bombed,” the resident, who also declined to be identified, told RFA on Christmas Day. “The sermons are as short as possible, not only at Christmas but every Sunday too,” she said. The chief of the junta, Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, attended a Christmas dinner on Sunday at St. Mary’s Cathedral in the main city of Yangon and reiterated a call for insurgents to make peace, saying his government was strengthening democracy. Anti-junta forces dismiss his calls as meaningless and say there is no basis for trusting the military, which overthrew a civilian government in 2021, imprisoned its leaders and has tried to crush all opposition. Edited by RFA Staff. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

US missile deployment in the Philippines is legitimate: Manila

MANILA – The Philippines’ acquisition and deployment of a U.S. mid-range missile system is “completely legitimate, legal, and beyond reproach,” its defense chief said on Tuesday. China protested against the plan by the Philippines to acquire a Typhon mid-range missile system from the United States to boost its maritime capabilities amid rising tensions in the disputed South China Sea. Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Mao Ning called the plan “provocative and dangerous,” and said on Monday it was an “extremely irresponsible choice” not only for the Philippine people and people of all Southeast Asian countries, but also “to history and to regional security.” Philippine Secretary of National Defense Gilberto Teodoro said any deployment for the security of the Philippines was its affair. “The Philippines is a sovereign state, not any country’s ‘doorstep’,” Teodoro said in a statement. He did not refer to the Chinese comment on the missile system but reiterated that the enhancement of Philippine defense capabilities was intended to serve its national interest and “not targeted against specific countries.” “Any deployment and procurement of assets related to the Philippines’ security and defense fall within its own sovereign prerogative and are not subject to any foreign veto,” Teodoro said. RELATED STORIES Philippines ratifies defense pact with Japan, amid China tensions China, Philippines trade accusations over South China Sea confrontation Philippines enacts laws asserting maritime claims China and the Philippines have been trading accusations of provocation and intimidation over escalating tensions in parts of the South China Sea that they both claim, especially near reefs that lie inside Manila’s exclusive economic zone, or EEZ, but are also claimed by Beijing. “If the Chinese Communist Party is truly intent on reducing tensions and instability in the region, they should … stop their provocative actions … withdraw their illegal presence from the Philippines’ EEZ, and adhere to International Law,” said Teodoro, who also accused Beijing of building up a nuclear arsenal and ballistic missile capability. Typhon system On Monday, Philippine army chief Lt. Gen. Roy Galido – while delivering his year-end report to an audience of domestic and foreign journalists in Manila – confirmed that the army has endorsed a plan to acquire a mid-range missile system “to boost the country’s capability in protecting its territory.” The mobile system, called Typhon, was deployed to the Philippines early this year as part of a joint military exercise with the U.S. military. Chinese defense minister Dong Jun said in June the deployment was “severely damaging regional security and stability.” The missile system, developed by U.S. firm Lockheed Martin, has a range of 480 kilometers (300 miles), and is capable of reaching the disputed Scarborough Shoal as well as targets around Taiwan. Philippine Army chief Lt. Gen. Roy Galido delivering his year-end report on Dec. 23, 2024, in Manila.(Jason Gutierrez/BenarNews) Galido said that the Typhon would “protect our floating assets,” referring to Philippine navy and coastguard vessels. The acquisition is taking place as the army is “tasked to come up with plans to contribute to the comprehensive archipelagic defense,” according to Galido, who added that “one of our inputs is to be able to defend this land through this type of platform.” Chinese spokeswoman Mao Ning criticized the plan, saying that the Philippines, “by bringing in this strategic offensive weapon, is enabling a country outside the region to fuel tensions and antagonism in this region, and incite geopolitical confrontation and arms race.” BenarNews is an RFA-affiliated online news organization. Edited by Mike Firn. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

Teenagers fight US militarization of Palau with UN complaint over rights violations

Read this story on BenarNews KOROR, Palau — School students in Palau are taking on the United States military with a legal complaint to the United Nations over a “rapid and unprecedented wave of militarization” in their Pacific island nation. They allege that American military activities are destroying ecosystems, disturbing sacred sites, threatening endangered species, and breaking laws that protect the environment and human rights. A group of children play near the ocean in Koror, Nov. 29, 2024.(Harry Pearl/BenarNews) She is one of the seven teenagers, aged between 15 and 18, leading the pushback against U.S. military activity. Over the past year they travelled the length of the country visiting defense sites, interviewing local communities and documenting environmental impacts. Last month the students filed a submission to the U.N. special rapporteur on the rights to a healthy environment and the special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Together with the Ebiil Society, a local nonprofit, and human rights lawyers in Guam, they alleged American military violations of environmental laws and indigenous rights in Palau. The group is among a young generation of Pacific activists using international legal mechanisms to fight for their rights, such as law students from Vanuatu who asked the International Court of Justice to give an opinion on states’ obligations to combat climate change. ‘Bulldozing’ through Palau Palau is one of three Pacific island countries including the Marshall Islands and Federated States of Micronesia that give the U.S. exclusive military authority in their territories in exchange for economic assistance under compacts of free association. The U.S. is now using the “compact provisions, which have never before been invoked, to justify a rapid and unprecedented wave of militarization throughout Palau,” according to the U.N. submission. The Palauan students’ complaint is focused on six U.S. military sites spread between Palau’s northernmost tip and its southernmost edge, including an over-the-horizon radar facility and a WWII-era airstrip being upgraded by U.S. Marines on the island of Peleliu. Ann Singeo, executive director of Palaun environmental nonprofit the Ebiil Society, on Nov. 27, 2024 in Koror.(Harry Pearl/BenarNews) U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, which oversees American forces in the region, did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. But Palau President Surangel Whipps rejected any accusations that environmental laws had been broken or that local communities had not been adequately informed about military projects. Whipps acknowledged there were concerns about militarization in the community, but argued that for a small nation like Palau, which has been subject to “unfriendly behavior” by China, having the protection of the U.S. was a good thing. “We’ve always been a target because of our location, whether we like it or not,” he told BenarNews in an interview. “During World War II, we were a target and that’s why Japan built all the infrastructure here and used Palau because of our location. “If you’re going to be a target, you need to make sure that you’re protected. Our forefathers decided that the best relationship that we could have with the United States is in free association … but as partners, we have some obligations.” Nest Mechaet, a state legislator for Elab hamlet, sits at her family’s traditional land in Ngaraard state, Palau, Nov. 30, 2024.(Harry Pearl/BenarNews) She said there were fears that earthmoving might damage historical sites and affect sediment flows into the marine environment nearby, which is home to endangered dugongs, turtles and saltwater crocodiles. “Some old people say there are ancient stone platforms here,” she told BenarNews, looking out over the bay below where the radar will be positioned. “There are mangrove clams, sea cucumbers, fish – you name it. People are out there for food.” It’s unclear what impact the Angaur lawsuit or calls for a review of the permit in Ngaraard will have on the radar, which the U.S. had originally aimed to complete by 2026. The U.S. radar system, which will add to American early-warning capabilities for the western Pacific, is expected to bring economic benefits to the island including higher paying jobs and rental incomes. A sign at the ferry dock in the city of Koror calling for a ‘No’ vote against a proposed amendment to the Peleliu constitution, Nov. 25, 2024.(Harry Pearl/BenarNews) On the island of Peleliu, where U.S. Marines are revamping the Japanese wartime airfield, some local chiefs and former legislators are seeking an injunction against a proposed constitutional amendment concerning military activity in the state. Peleliu’s constitution currently requires the approval by 75% of residents in a referendum for any permanent military facilities to be built on the island or training to take place – a provision adopted after WWII. Under the amendment, which was put on the ballot of a Dec. 3 state election, the article would be repealed and authority on military matters transferred exclusively to the governor and legislature, according to court documents reviewed by BenarNews. It also proposes reducing the size of the state government from 15 members to 11 and removing five seats reserved for traditional chiefs. Whipps described a lot of the criticism about U.S. military projects in Palau as “misinformation” and suggested it was possibly “another Chinese attempt to convince people that things are really worse than they really are.” But Singeo, from the Ebiil Society, said it was important to mobilize young people to fight for the “survival of a culture and nation.” “No matter how strong they are, how big they are, this is not their home,” she said. “For me as an adult, to not support the kids to do this is the same as condemning them to a future of chaos, conflict and keeping their head down not saying anything.” BenarNews is an RFA-affiliated online news organization. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

A long-deferred dream realized. My reunion with my mother

Uyghur-American lawyer Nury Turkel hadn’t seen his mother in more than two decades. But she and two other Uyghurs, who were subjected to an exit ban in China, were included in a prisoner swap between the United States and China in November. Here, Turkel relates the story of his long-delayed reunion with his mother. My heart is overwhelmed with joy, relief and renewed hope this holiday season. After more than 20 years of separation, I am finally reunited with my beloved mother here in America. The most precious moment was seeing her embrace her grandchildren for the first time — a long-deferred dream finally realized. For much of my life, holidays like Thanksgiving felt hollow because of our family’s fractured reality. I have always been close to my mother. Our family often joked that I was an only child, although I have three younger brothers. My mother relied on me when she felt stressed or sad. This deep bond traces back to my birth during China’s notorious Cultural Revolution in a Communist reeducation camp. Chinese authorities used this bond to torment me, despite my having lived in America as a free Uyghur for nearly three decades. I had not seen my mother since 2004 and had spent only 11 months with my parents since leaving China 29 years ago. While on a flight from Rome, Secretary of State Antony Blinken speaks to the people released by China, November 2024. I was born in 1970 in the midst of unspeakable horrors. My mother had already spent over six months in the camp before my birth. Severely malnourished and suffering from a fractured hip and ankle, she gave birth to me while in a cast from the chest down. We lived under dire conditions, marked by scarce food and constant surveillance. I was malnourished and frail, a living testament to my mother’s suffering. The first several months of my life were spent in detention alongside her. We were starved, isolated and stripped of our dignity. Yet, through it all, her resilience and unwavering strength sustained me through the darkest times. In the summer of 1995, driven by a long-standing admiration for freedom in America and inspired by the end of the Cold War, I arrived in the United States as a student and was later granted asylum. Witnessing the collapse of former Soviet blocs, including Central Asia regions with deep cultural, historical and geographical ties to the Uyghur people, reinforced my desire for freedom and higher education. Despite my life as a free American and four years as a U.S. official, the past continued to haunt me. I endured years of sanctioned isolation, unable to be there when my father passed away in 2022. The Chinese government’s retaliation intensified, barring my mother from traveling and isolating her socially. My mother, facing severe health issues, remained under constant surveillance and travel restrictions. These are common sufferings and struggles for countless Uyghurs around the world. I have been sanctioned by both China and Russia for what appears to be retaliation against my service in the U.S. government and decades-long human rights advocacy work. Every attempt to reunite us was blocked, and my mother’s deteriorating health intensified the urgency. Yet, our determination to be together never wavered. On the eve of Thanksgiving, a miracle unfolded. Three days before her arrival in America, security officials in Urumqi notified my mother that she would need to get ready to go to Beijing at 4 a.m. the next day. She had about 20 hours to prepare for this trip. It was a journey she had longed for with hope and prayer for over two decades. In her final hours in China, she visited my father’s grave to say goodbye one last time, honoring their shared history and fulfilling a deeply personal need for closure before embarking on her long-awaited journey. They had been married for 53 years, sharing countless memories, from raising a family to weathering life’s challenges with unwavering love and commitment. On the night of Nov. 24, around the same time Chinese security informed my mother about the trip to Beijing, I received a call from the White House notifying me about developments I would learn more about the next day at a pre-planned meeting with a senior National Security Council official. I woke up my wife and children and shared the news. I felt relieved, excited and deeply grateful. Early on Thanksgiving morning, while driving to Dulles Airport for my flight to Texas where I was to meet my mother, I received a call from a U.S. official who put her on the phone. “Son, I am on a U.S. government plane and free,” she said. “I don’t know what to say. So happy beyond words.” For so long, I lived with the constant fear that one day I might receive the unthinkable news of my mother’s imprisonment — or worse — just as I lost my father over two years ago. But when I heard my mother’s voice, hope prevailed, and the long-held darkness lifted. That fear and the unthinkable are no longer part of my life. At the U.S. Joint Base in San Antonio, Texas, I watched my mother descend the plane’s stairs, supported by a U.S. diplomat and greeted by a military commander in uniform. A wave of emotions washed over me, and I ran toward my mother. We embraced, tears streaming down our faces, overwhelmed by the reality of our long-awaited reunion. Her first words — “Thank God I’m here with you, and I won’t be alone when I die” — shattered and mended my heart all at once. This has been more than a reunion. It’s the restoration of a piece of my soul. Words cannot fully express my gratitude. On Thanksgiving morning, my brother, who had flown with me to Texas, and I brought our mother to Washington. Watching her embrace her grandchildren for the first time was a moment of incredible joy and healing. Though my father…

Hong Kong verdict against Yuen Long attack victims prompts widespread criticism

The verdict by a Hong Kong court has generated widespread criticism after it found seven people — including former lawmaker Lam Cheuk-ting — guilty of “rioting” when they tried to stop white-clad men wielding sticks from attacking passengers at a subway station in 2019. Exiled former pro-democracy lawmaker Ted Hui, who like Lam is a member of the Democratic Party, accusing authorities of “rewriting history.” “It’s a false accusation and part of a totally fabricated version of history that Hong Kong people don’t recognize,” Hui told RFA Cantonese after the verdict was announced on Dec. 12. “How does the court see the people of Hong Kong?” he asked. “How can they act like they live in two separate worlds?” The District Court found Lam and six others guilty of “taking part in a riot” by as dozens of thugs in white T-shirts rained blows down on the heads of unarmed passengers — including their own — using rattan canes and wooden poles at Yuen Long station on July 21, 2019. Lam, one of the defendants in the subversion trial of 47 activists for holding a democratic primary, is also currently serving a 6-years-and-9-month prison sentence for “conspiracy to subvert state power.” Wearing a cycle helmet, Galileo, a pseudonym, left, tries to protect Stand journalist Gwyneth Ho, right, during attacks by thugs at Yuen Long MTR, July 21, 2019 in Hong Kong. “I was panicky and scared, and my instinct was to protect myself and others,” he said. According to Galileo, Lam’s actions likely protected others from also being attacked. “I felt that his presence made everyone feel calmer, because he was a member of the Legislative Council at the time,” he said of Lam’s role in the incident. “He kept saying the police were coming, and everyone believed him, so they waited, but the police never came.” Police were inundated with emergency calls from the start of the attacks, according to multiple contemporary reports, but didn’t move in until 39 minutes after the attacks began. In a recent book about the protests, former Washington Post Hong Kong correspondent Shibani Mahtani and The Atlantic writer Timothy McLaughlin wrote that the Hong Kong authorities knew about the attacks in advance. Members of Hong Kong’s criminal underworld “triad” organizations had been discussing the planned attack for days on a WhatsApp group that was being monitored by a detective sergeant from the Organized Crime and Triad Bureau, the book said. Chased and beaten According to multiple accounts from the time, Lam first went to Mei Foo MTR station to warn people not to travel north to Yuen Long, after dozens of white-clad thugs were spotted assembling at a nearby chicken market. When live footage of beatings started to emerge, Lam called the local community police sergeant and asked him to dispatch officers to the scene as soon as possible, before setting off himself for Yuen Long to monitor the situation in person. On arrival, he warned some of the attackers not to “do anything,” and told people he had called the police. Eventually, the attackers charged, and Lam and others were chased and beaten all the way onto a train. One of the people shown in that early social media footage was chef Calvin So, who displayed red welts across his back following beatings by the white-clad attackers. So told RFA Cantonese on Friday: “The guys in white were really beating people, and injured some people … I don’t understand because Lam Cheuk-ting’s side were spraying water at them and telling people to leave.” He described the verdict as “ridiculous,” adding: “But ridiculous things happen every day in Hong Kong nowadays.” Erosion of judicial independence In a recent report on the erosion of Hong Kong judicial independence amid an ongoing crackdown on dissent that followed the 2019 protests, law experts at Georgetown University said the city’s courts now have to “tread carefully” now that the ruling Chinese Communist Party has explicitly rejected the liberal values the legal system was built on. RELATED STORIES EXPLAINED: What is the Article 23 security law in Hong Kong? Hong Kong police ‘knew about’ Yuen Long mob attacks beforehand EXPLAINED: Who are the Hong Kong 47? Nowadays, Hong Kong’s once-independent courts tend to find along pro-Beijing lines, particularly in politically sensitive cases, according to the December 2024 report, which focused on the impact of a High Court injunction against the banned protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong.” “In our view, at least some judges are issuing pro-regime verdicts in order to advance their careers,” said the report, authored by Eric Lai, Lokman Tsui and Thomas Kellogg. “The government’s aggressive implementation of the National Security Law has sent a clear signal to individual judges that their professional advancement depends on toeing the government’s ideological line, and delivering a steady stream of guilty verdicts.” Translated with additional reporting by Luisetta Mudie. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

EXPLAINED: Why are leaflets protesting North Korea dropped in Japan?

Read a version of this story in Korean An organization dedicated to advocating for South Koreans abducted by North Korea plans to air-drop anti-North Korean leaflets in Tokyo on this week. Specifically, the group plans to use drones to drop the leaflets — containing photos and stories of some of the 516 South Koreans kidnapped by North Korea over the years — over the headquarters of the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, which many regard as Pyongyang’s de facto embassy there. North Korea doesn’t have an embassy in Japan because the two countries don’t have formal diplomatic ties. What’s the goal of this tactic? The group is doing this because staffers at the headquarters of the pro-North Korean organization — also, abbreviated to Chongryon (in Korean) or Chosen Soren (in Japanese) — refused to accept a hand-delivered list of abductees, according to Choi Sung-ryong, the head of the South Korea-based Association of the Families of Those Abducted by North Korea. Choi said that dropping the leaflets on Chongryon headquarters is like sending them directly to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un — and he hopes that his efforts can prompt Pyongyang to acknowledge that it has abducted many South Koreans over the years. Choi said he would continue to distribute leaflets until this happens. “The leaflets include a request to quickly confirm whether the abductees are alive or dead,” said Choi. “We are asking Kim Jong Un to quickly confirm the fate of 516 family members. That’s why we’re protesting.” Zainichi Koreans in Japan pray for the late North Korean leader Kim Jong Il during a memorial service at a Korean cultural center in Tokyo on Dec. 29, 2011, shortly after his death. Its rival organization is the South Korea-aligned Korean Residents Union in Japan, referred to colloquially in Japanese and Korean using the abbreviation Mindan. Both organizations advocate for Zainichi Koreans living in Japan — which for most of the second half of the 20th century was the largest minority in the country, and is now the third largest. What does Zainichi mean exactly? In Japanese, it literally means “staying in Japan.” Today, there are hundreds of thousands of zainichi Koreans who live in Japan — they have been living there for generations, but for one reason or another they have not acquired Japanese citizenship. The history behind this is that when World War II ended in 1945, there were around 2.4 million Koreans in Japan, and while most of them returned to Korea over the next few months, around 640,000 stayed behind. A group of Japanese and zainichi Koreans stage a protest against Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara’s anti-foreigner remarks, in front of the Tokyo metropolitan government office April 12, 2000. Japan became party to several international human rights covenants in the 1980s and since the post-war period there has been a general change in mainstream Japanese attitudes towards minorities. But for much of the early postwar period, the community struggled economically, and community organizations emerged to counter discrimination against Zainichi. The Chosen Soren and Mindan groups have advocated for their rights in Japanese society and preservation of Korean culture and language among the community, including by securing funds from the South and North Korean governments to run schools for Zainichi children. Today, while there is greater acceptance of zainichi Koreans in Japanese society, they still face discrimination. Translated by Leejin J. Chung. Edited by Eugene Whong and Malcolm Foster. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

What’s Wrong with the Reports? (Part 1)

Explore Investigative Journalism Reportika’s comprehensive analysis of global indices and reports, including the World Press Freedom Index, Corruption Perceptions Index, Global Hunger Index, and more. Delve into critical sections such as methodological flaws, unexpected discrepancies, cultural biases, data limitations, and controversies. Our reports challenge assumptions, reveal hidden inaccuracies, and offer insights to foster informed debate.

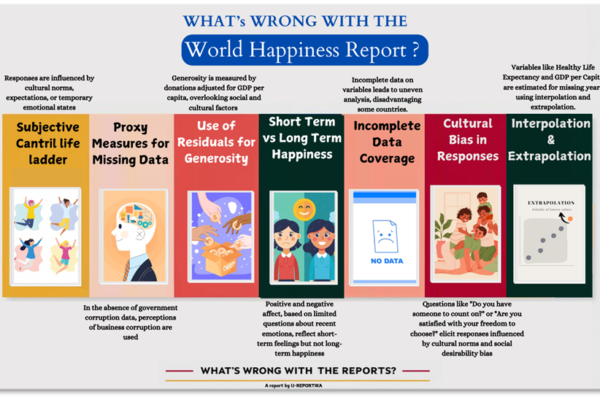

What’s Wrong with the World Happiness Report

The World Happiness Report faces several criticisms, including issues with the Gallup World Poll, which serves as a primary data source. Concerns have been raised about the subjectivity bias in self-reported responses, where people’s perception of happiness can be influenced by cultural norms and expectations.

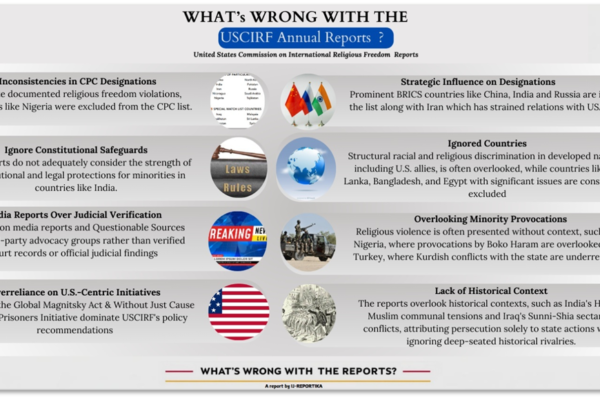

What’s Wrong with the USCIRF Report

Discover the hidden flaws in the USCIRF Annual Report, including strategic biases, methodological gaps, and lack of transparency, which challenge its credibility and impartiality on international religious freedom.

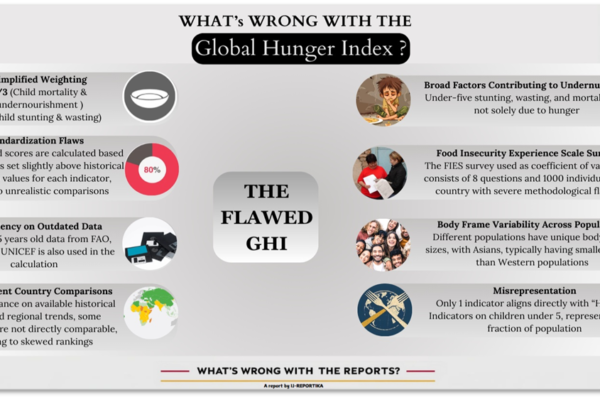

What’s Wrong with the Global Hunger Index

“The Global Hunger Index serves as a critical benchmark for global food security, but this investigative report by IJ-Reportika uncovers its methodological flaws. From outdated data to inconsistent scoring, these issues misrepresent nations’ progress and obscure systemic challenges, calling for urgent reforms to ensure accuracy and accountability.”