Around 1.7 million Indonesians living overseas are registered to vote in this month’s presidential and legislative elections, a mammoth task for the General Elections Commission, which has had to prepare 828 voting booths at Indonesian representative offices worldwide, as well as 1,579 mobile voting boxes and 652 drop boxes for absentee voting.

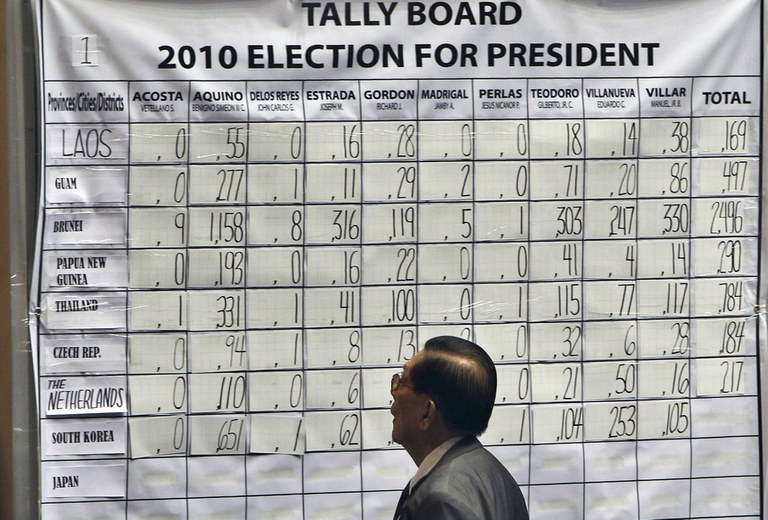

How many overseas Indonesians will actually turn out to vote is another matter, and will there be any further controversy after reports that ballots were given to overseas nationals too early? According to a review by the Philippines’ Commission on Elections published this month, of the estimated 10 million overseas Filipinos, only 1.6 million are registered to vote and only 600,000 (around 40 per cent) did so at the 2022 elections.

Most Southeast Asian governments, at least the more democratic ones, are looking at ways of reforming how overseas nationals vote. The Philippines’ electoral commission says it intends to have an online voting system in place by 2025 for overseas nationals, although there is still talk that this might be cost-prohibitive and could require digital voting to be rolled out at home too, which is simply too difficult for the election commissions of most Southeast Asian countries for now.

In Malaysia, where overseas balloting has been in something of a mess for the past decade, parliamentarians last month hit on fixed-term parliaments as one way to fix the problem.

However, it might be worth pondering why overseas voters are still asked to vote for representatives in parliament who live hundreds of miles away from them, whose priority is to represent constituents back at home, and who may know nothing about the concerns of overseas nationals.

Constituencies mismatched

In Indonesia, for instance, votes from overseas Indonesians go to deciding the seven seats in the House of Representatives sent by Jakarta II district. (Jakarta II, which is Central and South Jakarta, was chosen because that’s where the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is located.)

This may actually be superior to how other Southeast Asian states count overseas ballots – indeed, at least the seven congresspeople from Jakarta II district know they’re supposed to represent overseas constituents. Compare that to Thailand, where overseas voters select the candidates in the constituency where they are from or were registered, so a Thai living in London but who hails from, say, Chiang Mai province votes for the MPs from Chiang Mai province. But how can the MP from Chiang Mai province be expected to adequately represent overseas electors when perhaps only 0.1% of the ballots cast for them came from overseas?

Why not, instead, make overseas voters a separate district and allocate six or seven seats solely for them? They could have one seat for an MP representing Indonesians in North America, another for Indonesians in Europe, another for those in Northeast Asia, another for Southeast Asia, and so forth.

And these seats would be occupied by candidates who live overseas. Imagine the Indonesian congressperson who resides in Berlin, New York, Seoul, or Melbourne. They obviously would be able to understand better the concerns and problems facing other Indonesians living abroad.

Aloof from local politics

There’s a democratic element to this, too. An overseas MP wouldn’t have to mix daily with their peers in Manila, Kuala Lumpur or Jakarta. They would, on the one hand, remain aloof from the politicking and palm-greasing back home and, on the other hand, be able to bring new ideas learned from abroad back to their capitals.

They could attend parliamentary sessions every month or two, funded by the state, and spend most of their time abroad, where they could also work more closely with their country’s embassies in the regions they represent.

Currently, almost 10 million overseas Filipinos are represented by several government bodies, such as the Commission on Filipinos Overseas, an agency under the Office of the President. However, having overseas MPs in parliament would provide another layer of representation for nationals living abroad, allowing their voices to be heard by the government bodies and by overseas-based elected representatives.

Indeed, protecting the large population of overseas Filipinos is one of the three pillars of Manila’s foreign policy initially laid out in the 1990s, yet those emigrants have little legislative representation.

It isn’t a revolutionary idea to have overseas-based MPs represent overseas voters. France’s National Assembly has eleven lawmakers representing overseas constituencies. Italy’s parliament has had eight.

Global examples

Nor is it specifically a European idea. The Algerian parliament has eight MPs who represent overseas nationals. Angola, Cape Verde, Mozambique, Peru and Tunisia, to name but a few, also have some parliamentary seats set aside for overseas constituencies.

To quickly rebut one argument against it, it would not require a massive change to the composition of parliaments, nor would it require too many administrative changes. At the most, we’re talking about less than ten seats, so a fraction of parliament in a country like Thailand, whose National Assembly has 500 seats!

But if electoral commissions are now pondering ideas to better include their overseas nationals in the democratic process, it might be worth considering the more affordable and, perhaps, more democratic option of giving a handful of seats in parliament to overseas representatives.

Nor, indeed, would it be a terrible idea if campaigners in Southeast Asia’s autocracies suggested this as a rational way of protecting their overseas compatriots – all the while knowing that they’re smuggling something democratic into the conversation, however implicitly.

After all, even one-party states claim to listen to their parliaments and to protect their emigrants. Some 1 million Cambodians live abroad, most in Thailand but also Northeast Asia, Europe, Australia and North America.

Why not add a 26th consistency during the next general election and allow overseas Cambodians to elect six seats in the National Assembly directly, the same number of seats sent to parliament by the inhabitants of Siem Reap province, home to around 1 million people, too?

If the Communist Party of Vietnamese can stretch its tentacles abroad, why not allow a handful of delegates in the National Assembly to represent the 5 million Vietnamese living abroad?

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. As a journalist, he has covered Southeast Asian politics since 2014. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.