Authorities across China are tightening security and ramping up surveillance of dissidents ahead of the Tiananmen massacre anniversary, RFA has learned.

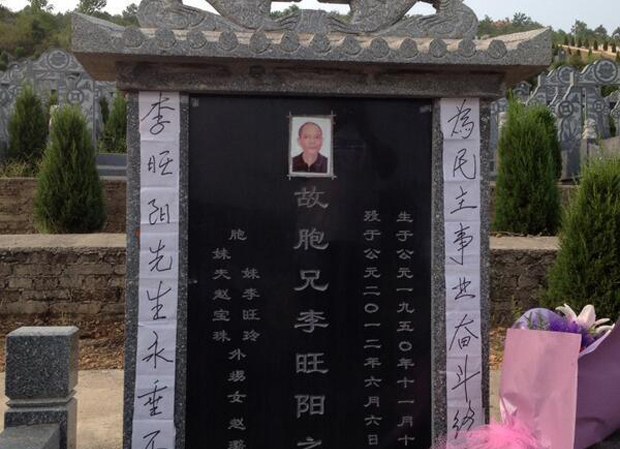

Ten years after the death of prominent labor movement leader Li Wangyang in police custody prompted suspicions of foul play, activists in the central province of Hunan said they will be marking that anniversary, as well as the 33rd anniversary of the June 4, 1989 massacre, at least in private.

“It’s the 10th anniversary of Li Wangyang’s death,” Hunan activist Ouyang Jinghua told RFA. “He passed away on June 6, which happened to be close to June 4 [the massacre anniversary].”

“He suffered a lot for the cause of democracy,” Ouyang said. “Everyone still remembers him.”

Ouyang said there had been some attempt to organize a collective commemoration for Li, but said it was unclear if it would go ahead, given the tightened security.

“Some people from Changsha, Hengyang and Zhuzhou are supposed to be coming, but we don’t know how many people will make it, due to the obstacles placed by the authorities,” he said. “It’s possible that none of them will be allowed to come.”

Ouyang said rights activists and democracy campaigners still hope for posthumous justice for Li.

“We have a lot of doubts about the explanation of the cause of his death,” Ouyang said. “The authorities should explain it clearly, but I don’t think they will, because to do so would shake their basis to hold power; the whole regime.”

‘Stability maintenance’

Prominent dissident and Hunan native Zhu Chengzhi has also been a major focus for the local authorities’ “stability maintenance” operations.

Zhu, who was detained in April 2018 after visiting the grave of Mao-era dissident Lin Zhao, was released from Jiangsu’s Dingshan Prison on Jan. 26 after serving a three-year, nine-month jail term for “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble,” a charge frequently used to target peaceful critics of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

Zhu became one of China’s most prominent rights activists after he spoke out Li Wangyang’s death in 2013, and had previously been held on suspicion of subversion after he questioned the official verdict of suicide.

“Zhu Chengzhi recently arrived in Changsha, Hunan, and some friends in the city met up with him,” Ouyang told RFA. “Anyone who met with him was called in to ‘drink tea’ with the state security police.”

“When Zhu Chengzhi arrived in Loudi, a friend from Guangxi came to visit him … [but then] Guangxi [officials] immediately rushed to Loudi and took away my friends from Guangxi,” he said.

Dissidents in Beijing said that fewer of them are being forced to leave town ahead of the anniversary this year, owing to COVID-19 travel restrictions.

Political commentator Ji Feng said he had been forced to leave, however, as his registered household is in the southwestern province of Guizhou.

“They’re taking me away [on Tuesday] morning,” Ji told RFA. “I will have the same state security bureau chief with me, eating and drinking with me, around June 4.”

“If they keep me drinking and chatting, I won’t be able to do anything else.”

Warnings, forcible relocations

He said outspoken veteran political journalist Gao Yu, dissident artist Yan Zhengxue and writer Jiang Qisheng were all staying in Beijing due to the COVID-19 restrictions.

Meanwhile, a dissident in the southern province of Guangdong said many activists in the province had been warned off talking about sensitive topics around the anniversary, with some forcibly relocated.

“State security police moved me into a basic house about 20 kilometers from Enping,” the dissident said. “It’s pretty remote; there’s nobody else living round there, but there are surveillance cameras everywhere.”

“As soon as I leave my house, my phone will ring, and they’ll ask me where I’m going,” they said.

Li Wangyang, 62, died at a hospital in Shaoyang city in the custody of local police. When relatives arrived at the scene, his body was hanging by the neck from the ceiling near his hospital bed, but was removed by police soon afterwards.

Police took away Li’s body after his death was discovered and kept it in an unknown location, Li’s relatives said.

Relatives, friends, and rights groups have all called into question several details of both circumstance and timing which they say point to the possibility of foul play, including photographs distributed on the Chinese microblog service Sina Weibo, which showed Li’s feet touching the floor.

Li, a former worker in a glass factory, was jailed for 13 years for “counterrevolution” after he took part in demonstrations inspired by the student-led protests in Beijing, and for a further 10 years for “incitement to overthrow state power” after he called for a reappraisal of the official verdict on the crackdown.

He was blind in both eyes and had lost nearly all his hearing when he was finally released from prison in May 2011, his family said.

Li’s death came as Chinese authorities moved to crack down on dissidents and rights activists around the country, in a bid to prevent any public memorials on the 23rd anniversary of the June 4, 1989 bloodshed.

The authorities have refused to make public the results of an autopsy on Li’s body.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.