Category: Americas

Uneasy calm in Dhaka under curfew, police arrest hundreds for ‘violence’

An uneasy calm prevailed in Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka on the third day of a nationwide curfew Monday, as authorities said they had arrested hundreds of people for their alleged involvement in violence during protests that turned deadly last week. While there were no protests or street clashes, two people badly hurt in the earlier violence succumbed to their injuries on Monday. This took the death toll to at least 138 in a week of street clashes that began as protests against a discriminatory quota system for government jobs and became a wider agitation against Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s 15 years in power. Hasina and other government officials blamed opposition groups for last week’s deadly violence, according to footage from Channel 24 distributed by Reuters news agency. But university students, who began the protests after the quotas were reinstated by a court last month, have alleged that it was members of the student wing of Hasina’s Awami League, aided by the police, who incited the clashes. A man rides his motorbike on a mostly empty street past vehicles that were set on fire during clashes among university students, police and government supporters, after violence erupted during what were initially protests against government job quotas,Dhaka, July 22, 2024. (Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters) U.S. State Department spokesman Matthew Miller on Monday said the U.S. condemns “reported shoot-on-sight orders” that are part of a crackdown on the protests. “The United States is concerned by reports of ongoing telecommunications disruptions in Bangladesh,” Miller told reporters, referring to a state-imposed internet and mobile connectivity shutdown that continued Monday, reported Reuters. Habibur Rahman, Dhaka Metropolitan Police’s commissioner, told reporters on Monday that police have arrested more than 600 people, mostly in Dhaka, for violent acts during the protests. A senior official from the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party, Zahir Uddin Swapon, and a minor party’s leader, Md. Tarek Rahman, were arrested Monday. Tarek’s wife, Tamanna Ferdosi Sikha, told BenarNews that a joint force of police, border guard and soldiers entered their house at about 2:30 am and picked up Tarek and his brother. “They seized a computer and other digital devices from our house,” she said. Students give a 48-hour ultimatum After the curfew that was imposed Friday was indefinitely extended on Sunday, Bangladesh Army chief Waker-uz-Zaman told reporters that more time was needed to “normalize” the situation. “Many state properties were vandalized … there are many ways of staging protests,” he said Monday. “But carrying out attacks on state properties is not wise.” Several government buildings and properties were set on fire last week during the clashes, including the state broadcaster and a train station. The protesting students were not mollified by the Supreme Court on Sunday ending most of the quotas in civil service jobs. The court lowered the number of reserved jobs to 7% from 56%. A key plank of the quota system was the reservation of civil service jobs for relatives of those who fought in Bangladesh’s 1971 independence war. The students also demanded that the internet be restored and security forces be withdrawn from university campuses. “We are issuing an ultimatum … 48 hours to stop the digital crackdown and restore internet connectivity,” Hasnat Abdullah, coordinator of the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement, told the Associated Press. “Within 48 hours, all law enforcement members deployed at different campuses should be withdrawn, dormitories should reopen and steps should be taken so that students can return to the [residence] halls.” Asif Nazrul, a professor in Dhaka University’s law faculty, said protesting students might only be satisfied if authorities apologize for unlawful actions, arrest armed cadres of the ruling Awami League’s student and youth wings and arrest police and elite Rapid Action Battalion members who fired on unarmed civilians. “Over 150 people died and thousands of protesters were injured in the uprising. I think the protest will not end with the judgment of the Supreme Court. Bangladesh’s people are not so foolish,” he told BenarNews. The Rapid Action Battalion has previously been accused of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings and the use of torture and the U.S. has imposed financial sanctions on it for “serious human rights abuses.” Two auto rickshaws are seen on an otherwise empty road during a nationwide curfew in the Jatrabari area in Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, July 22, 2024. [Jibon Ahmed/BenarNews] Some students are also demanding Hasina apologize or retract her comments from a week ago, when she said anti-quota protesters were akin to collaborators with Pakistan in the 1971 war Bangladesh fought to separate from that nation. The protests spread after Hasina’s comments. Reuters video showed her telling business leaders at a meeting in her Dhaka office that opposition forces were responsible for vandalism, arson and murders during the protests. Hasina’s advisor, Salman F. Rahman, said the student movement had been hijacked by people who wanted to overthrow the government. “There was a big conspiracy, they tried to ensure the fall of the government,” Rahman said. Another Hasina administration member, Nasrul Hamid, state minister for power and energy, claimed that the clashes caused U.S. $85 million in damages to power equipment. “We are trying to identify the people involved in such sabotage and they must be prosecuted,” he said. Bangladesh army personnel stand guard near the parliament house during a curfew imposed after clashes during anti-quota protests turned deadly, Dhaka, July 22, 2024. (Munir uz Zaman/AFP) Meanwhile, average Bangladeshis are bearing the brunt of the curfew, according to their accounts and those of vegetable, fruit and meat sellers. Abdul Baten, who operates a garment factory in an area called Mirpur-11, told BenarNews that prices of staple foods have risen. “We mainly depend on potato, egg, broiler chicken skin and leg, and lentils. A dozen eggs now costs 160 taka, up from 135,” he said. The problem, said vegetable trader Nur Mohammad, is that no produce is coming into Dhaka. “There is an abundant supply of vegetables outside Dhaka. But due to the curfew it cannot be transported here,” he told BenarNews. “Unless the supply chain is restored, the prices will not come down,”…

Nguyen Phu Trong left Vietnam’s Communist Party ripe for strongman rule

On July 19, the Vietnamese Communist Party announced the death of its general secretary, Nguyen Phu Trong. The previous day, it announced that Trong, 80, ostensibly the most powerful politician in the country, had been relieved of his duties for health reasons. He had missed several key meetings in recent months, and even when he did attend, he appeared shaky and unwell. He suffered a stroke a few years ago but seemingly bounced back. However, his near-unprecedented third term in office has been cut short. To Lam, the public security minister and promoted to state President last month, will now assume Trong’s duties. Having led the party since 2011, Trong attempted to reinvigorate an institution that, by the early 2010s, had become bogged down by individual rivalries, profit-seeking, and self-advancement. A man rides past a poster for the 13th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam in Hanoi on Jan. 22, 2021. (Nhac Nguyen/AFP) Corruption was so rampant the public was mutinous. Ideology and morality had fallen by the wayside. Pro-democracy movements threatened its monopoly on power. The private sector was not just fantastically wealthy, but desired more political power. But in what condition does Trong leave the institution he sought to fix? Externally, its monopoly on power is safer. It has increased repression of activists and democrats while appeasing the public through its high-profile takedown of the corrupt. The private sector has been constrained, too, so poses no threat to the party’s political authority. The economy has insulated the party from any meaningful repercussions from the West over human rights. ‘Blazing Furnace’ Within the Communist Party, however, Trong leaves behind a mess. Lam, as public security minister, and Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, artfully used Trong’s signature “Blazing Furnace” anti-corruption campaign to advance their own interests, effectively purging anyone who might rival them for Trong’s job in 2026. More Politburo members have been sacked than at any time in memory. Two presidents have “resigned” in as many years. The Politburo is now filled mostly with military personnel and securocrats, the only two factions – and sometimes rivals – left with power. Lam, if he does formally become acting general secretary, which the Politburo will have to vote on, is in a prime position to maintain the job in 2026. One imagines he has very different ideas about the nature of the Communist Party than Trong. Early in the anti-corruption campaign, Trong remarked that he did not want to “break the vase to catch the mice.” That metaphor implied that tackling corruption should shield a delicate Communist Party, not smash it to pieces. Vietnam’s President To Lam, front right, and Cambodia’s Defense Minister Tea Seiha, back right, pay their respects in front of honor guards at the Independence Monument in Phnom Penh on July 13, 2024. (Tang Chhin Sothy/AFP) However, in his quest to rid corruption from a corrupt institution, he eroded almost every check the Communist Party of Vietnam had to prevent a supreme leader figure from rising to the top. Trong violated the three major “norms” that the party introduced in the early 1990s. Politburo members were expected to retire at 65, and individuals could only occupy the most senior positions for a maximum of two terms. More importantly, no one person could hold at the same time two of the four most powerful positions: General Secretary, State President, Prime Minister, and Chair of the National Assembly. This “four pillar” (tu tru) system created a form of succession plan. Regular reshuffles and a separation of powers amongst the political elite would prevent the Communist Party from tilting towards dictatorship. Shattering the norms The norms created a structure in which politicians could fight over policies, often brutally, but without the entire apparatus collapsing because of division. There could be a regular rotation between different factions and geographic networks, meaning no one group was ascendant for too long. Hanoi called this “democratic centralism.” Of course, it’s not democracy, but it’s a form of pluralism that, in theory, had prevented the party from descending into dictatorships like North Korea, Cuba, or China under Xi Jinping. Trong broke every one of these rules. Between 2018 and 2021, he held the posts of party general secretary and state president simultaneously, the first person to do so since 1986. (Lam seems likely to repeat that.) Trong passed away during his third term as party chief, the first leader since Le Duan to have that record. He not only constantly had the party flout retirement-age limits for himself – he should have stepped down in 2021, if not earlier – but such exemptions have been handed out like confetti during his tenure. Vietnam’s Communist Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong addresses a press conference after the closing ceremony of the Communist Party of Vietnam 13th National Congress in Hanoi on Feb. 1, 2021. (Manan Vatsyayana/AFP) At the same time, his anti-graft campaign has centralized power among an increasingly small number of Politburo members. Provincial party politics have been purged and constrained to give more power to the central party apparatus. The party dominates the government. The public security ministry is all-seeing. This was always going to happen. How else do you clean up an uncleanable organization in which power flows up and discipline is enforced only by those above you? The campaign increases the necessity of one section of the party to maintain power indefinitely. Who designates what is the true morality and which cadres are truly moral? Well, a certain clique of the party running the anti-corruption campaign In one speech on the theme, Trong urged the party to “strengthen supervision of the use of the power of leading cadres, especially the heads, push up internal supervision within the collective leadership; make public the process of power use according to law for cadres and people to supervise.” The purge is designed to enforce the view that no one has absolute power above the party. Anyone who uses the power must serve the…

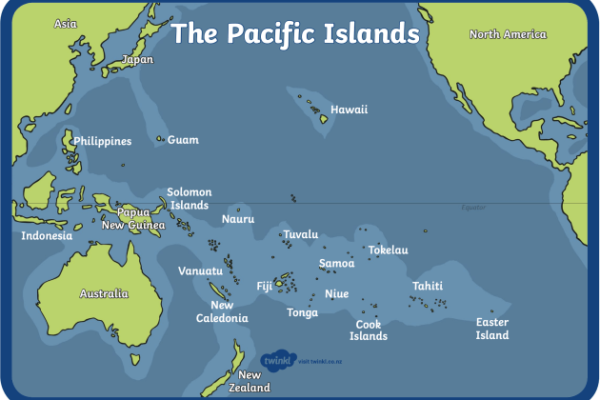

A palm reading: Japan’s navigation plan for Pacific waters

The triennial meeting of the Japanese Prime Minister with the leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum – referred to as PALM – is normally not much of an attention grabber. But this year’s meeting, which has just concluded in Tokyo, makes it clear that Japan is looking to significantly ramp up its presence in the region. This comes on the back of increased bilateral engagement – think new embassies in Kiribati and Vanuatu – and a reinvigorated QUAD with a focus on resource and burden sharing among the membership of the strategic security partnership (Australia, India, Japan, USA). The joint declaration from this their tenth meeting, known as PALM10, with its associated action plan sets out what we can expect from Japanese engagement with the Pacific over the next three years. The use of the seven pillars of the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent as a structure for future engagement is notable. The Blue Pacific concept was developed by Pacific nations as a home-grown framing to address their challenges. Other partners have inserted the term Blue Pacific into announcements and documents. However, this takes the recognition of the Pacific’s own framework to another level. It is particularly significant given that Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe coined the term Indo-Pacific, which many in the Pacific islands region have resisted. Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum Baron Waqa (L) and Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida shake hands during the opening session of the 10th Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM10) in Tokyo on July 18, 2024. (AFP) PALM10 sees a move to an “All Japan” approach to working with Pacific partners. Whilst several Japanese agencies are referenced in the outcome documents, the most notable is the prominence of the Japanese Self-Defense Force in future engagement. Japan’s military impacts in the Pacific islands region are well known and loom large in the regional memory. While the PALM10 action plan references the continuation of activities related to World War II, such as retrieval of remains and clearance of unexploded ordnance, new activities will see the Japanese presence in the region take on a markedly military aspect. This will add to what is an already crowded environment in which defense diplomacy has been increasing in recent years. However, Japan’s use of this strategy has been relatively limited until now. The PALM10 action plan refers to increased defense “exchanges” to consist of port calls by Japanese Defense Force aircraft and vessels. This may not be as easy to achieve as Tokyo officials might like. At the same time as PALM10 was in session in Tokyo, Vanuatu’s National Security Advisory Board refused a request for a Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force vessel to dock in Port Vila. The reasons for the refusal remain unclear. Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida (C) speaks during the opening session of the 10th Pacific Islands Leaders Meeting (PALM10) in Tokyo on July 18, 2024. (AFP) Other examples of increased use of the JSDF are the provision of capacity building to Pacific personnel for participation in peace-keeping operations and inclusion of a Self-Defense Unit in disaster relief teams to be deployed to Pacific island countries at their governments’ request. At the end of the Action Plan are items for “clarification.” Included in the list (of three) for Japan to clarify are two that continue this push for increased defense diplomacy. They are: a proposal to accept Pacific cadets into the National Defense Academy of Japan and to use the Japan Pacific Islands Defence Dialogue to foster “mutual understanding and confidence building.” The JPIDD has met twice, most recently earlier this year. We are now into the Pacific meeting season and in six weeks the 53rd Pacific Islands Forum Leaders Meeting will convene in Nuku’alofa, Tonga. Japan is a longstanding dialogue partner of the forum. The ongoing review of regional architecture includes revisions to how dialogue partners are selected and accommodated. What was discussed and agreed at PALM10 will play a role in determining where at the Blue Pacific table Japan will sit.

Anti-junta forces capture camps in central Myanmar township

An anti junta group in Myanmar’s Mandalay region is continuing to make gains in a key township following the collapse of a truce between insurgent armies and the military who seized power in a 2021 coup. The Mandalay People’s Defense Force, or PDF, captured a junta camp at the Alpha cement factory in Madaya township on July 14, and one at Taung Ta Ngar two days later, it said in a statement on Tuesday. Madaya is just 30 km (19 miles) north of Mandalay, the capital of the region and Myanmar’s second-largest city. The Mandalay PDF has been fighting alongside the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, or TNLA, since late October 2023. The TNLA, which has also teamed up with the Arakan Army and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army as part of the Three Brotherhood Alliance, pushed back junta forces in several regions before agreeing a shaky China-brokered truce with the junta in January. When the ceasefire collapsed on June 25, the TNLA attacked Mandalay’s Mogoke township and several towns in Shan state to the region’s east, while the Mandalay PDF focused much of its attention on Madaya and Singu townships in Mandalay region. The defense force said it had captured 28 junta camps as of Wednesday. Weapons and ammunition seized after Mandalay PDF captured the junta base at the Alpha cement factory in Madaya township, Mandalay region in a photograph released on July 16, 2024. (Mandalay PDF) Mandalay PDF spokesman Osmon, who goes by one name, told Radio Free Asia Myanmar’s military suffered heavy losses in the battle for Madaya. “There were many casualties on the side of the junta in these operations. We have seized corpses and arrested junta soldiers,” he said. “There were some casualties on the side of Mandalay PDF.” Osmon didn’t disclose the numbers of casualties on either side but said the PDF took more than 150 prisoners. He added the group is now engaged in a fierce battle with junta forces at Madaya’s Kyauk Ta Dar base. RELATED STORIES Myanmar junta steps up security in Mandalay as fighting spreads across region Thousands stuck between checkpoints on Myanmar road amid renewed fighting Thousands displaced in Myanmar’s Mandalay region On Tuesday, three people were killed when a shell hit Madaya town, close to its train station and main market. “It happened around 8 a.m.,” said a resident who didn’t want to be named for fear of reprisals. “A 44-year-old woman, a 30-year-old woman and a two-year-old girl were killed.” The man said he didn’t know which side had fired the shell, while another resident said the blast happened close to where junta troops were stationed. “It was about 10 to 14 meters away from them,” he said, also requesting anonymity for security reasons. “It was also close to where the junta soldiers always come to drink tea.” RFA phoned the junta spokesman for Mandalay region, Thein Htay, for details on the fighting in Madaya, but he did not answer calls. The National Unity Government, a shadow government formed by members of the civil administration ousted in the 2021 coup, said on June 27 that PDFs and their allies have made sweeping gains in Mandalay region and Shan state to the east, in a campaign it dubbed “Operation Shan-Man.” The Mandalay PDF said it had captured 11 junta camps in Singu township, 80 km (50 miles) north of Mandalay city, by July 7. Now the junta is fighting back, damaging around 100 houses and injuring more than 20 people in airstrikes on July 16, as it seeks to flush PDF forces out of Singu town. The PDF’s Singu-based head of information, Than Ma Ni, said the junta carried out more than 20 airstrikes on Tuesday and also bombarded the town with heavy artillery. “The junta’s air force has been striking all day as Mandalay-PDF has taken over Singu town,” he said Wednesday. “There were no deaths, but those who were hit by shrapnel have been moved to a safe place and are receiving medical treatment. The entire town was pretty much destroyed.” Translated by RFA Burmese. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

Junta deploys first round of military recruits to Myanmar’s frontlines

The first round of soldiers recruited under Myanmar’s controversial military draft law have completed their training and are being deployed to the frontlines of the junta’s war against rebels in the country’s remote border areas, their family members said Tuesday. The deployment marked the latest chapter in the junta’s bid to shore up its forces amid heavy losses against various ethnic armies and rebel militias since its 2021 coup d’etat, prompting the junta to enact the People’s Military Service Law in February. Under the law, men between the ages of 18 and 35 and women between 18 and 27 can be drafted to serve in the armed forces for two years. The announcement triggered a wave of assassinations of administrators enforcing the law and drove thousands of draft-dodgers into rebel-controlled territory and abroad. The military carried out two rounds of conscriptions in April and May, training about 9,000 new recruits in total. A third round of conscription began in late May, with draftees sent to their respective training depots by June 22. The first batch of recruits completed their three-month training on June 28, and family members told RFA Burmese on Tuesday that the new soldiers were sent to conflict zones in Myanmar’s Rakhine and Kayin states, and Sagaing region, beginning in early July. While the junta has never said how many recruits were trained in the first group, a mid-April report by the Burmese Affairs and Conflict Study, a group monitoring junta war crimes, indicated that it was nearly 5,000 young people from across the country. RELATED STORIES Thailand, Myanmar sign agreement on extradition of criminal suspects Junta military preparations point to brutal next phase in Myanmar conflict Dozens of officials carrying out Myanmar’s draft have been killed “My husband told me that orders from [the junta capital] Naypyidaw directed the deployment of new recruits from training batch No. 1 to conflict-affected areas, including Rakhine state,” said Nwe Nyein, the wife of a new recruit from Ayeyarwady region. “They [the junta] had previously said that new recruits under the People’s Military Service Law would not be deployed to the frontlines,” she said. “However, I am worried because my husband was sent to the remote border areas.” Nwe Nyein said that the second batch of recruits are expected to complete their military training on Aug. 2 and reports suggest that they will also be sent to the frontlines. Used as ‘human shields’ A resident of Myanmar’s largest city Yangon, who requested anonymity for security reasons, said that some people close to him had been injured in battles in northern Shan state and have since returned home. “A young man from our town was shot in the arm, but he never underwent an operation to remove the bullet,” the resident said. “He also said that almost all the new recruits sent to the frontlines had been killed, and their families didn’t even receive their salaries.” Recruits from the first batch of training under Myanmar junta’s people’s military service law seen on July 16, 2024. (Pyi Thu Sitt via Telegram) In southern Myanmar’s Tanintharyi region, residents told RFA that the junta is deploying new recruits to battle. Min Lwin Oo, a leading committee member of the Democracy Movement Strike Committee-Dawei, condemned the deployment of new recruits with only short-term military training, suggesting that they are being used as “human shields.” Flagging morale Former Captain Kaung Thu Win, who is now a member of the nationwide Civilian Disobedience Movement of former civil servants that left their jobs in protest of the military’s power grab, told RFA that the junta urgently needs more soldiers, and he expects that nearly all new recruits will be sent to the frontlines. “About 90% of these new forces will be dispatched to the battlegrounds, regardless of whether they engage in combat [with rebel groups] or target people [civilians],” he said. “Their [the junta’s] main objective is to ensure they have more soldiers equipped with guns.” Kaung Thu Win also said that the junta faces many challenges in its propaganda efforts to persuade new recruits to fight, but is also increasingly unable to trust its veteran soldiers as losses mount. Recruits from the first batch of training under Myanmar junta’s people’s military service law seen on July 16, 2024. (Pyi Thu Sitt via Telegram) Than Soe Naing, a political commentator, slammed the junta over the reported deployment and echoed the former captain’s assessment of the military’s low morale. “Young people are being sent to die after … [mere] months of military training,” he said. “Even veteran soldiers in their 60s who have been sent to the battlefield have lost their motivation.” 5 years of service? The junta has yet to release any information about the deployment of new recruits to the frontlines. Meanwhile, although the People’s Military Service Law states that new recruits must serve for a total of two years, reports have emerged that the junta is telling soldiers that they will have to fight for five. Junta officials have publicly denied the reports. Attempts by RFA to contact the office of the chairman of the Central Body for Summoning People’s Military Servants in Naypyidaw for further clarification went unanswered Tuesday. Translated by Aung Naing. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.

Myanmar junta steps up security in Mandalay as fighting spreads across region

Junta forces have tightened security in Myanmar’s second-biggest city, Mandalay, while shelling civilians elsewhere in the region, after coming under renewed attack from an alliance of insurgent forces battling to end military rule. A shell killed a seven-year-old boy and a woman in her 30s after it exploded in a residential area of Mandalay region’s Mogoke town on Monday evening, residents told Radio Free Asia Tuesday. Another four-year-old girl and a 60-year-old woman, as well as a woman and man both in their 30s, are in critical condition, said one Mogoke resident, asking to remain anonymous for security reasons. “A child and a grandmother were seriously injured by shrapnel that hit them in the neck,” he said. “It was not easy to send them to the hospital, so they were treated at home by people who have some medical knowledge.” The shells were fired from a junta camp on Strategic Hill in eastern Mogoke, a ruby-mining town about 200 km (120 miles) north of Mandalay city. Over half the town’s population has fled after fighting intensified between junta troops and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, or TNLA, which has taken control of western Mogoke, residents said. RELATED STORIESMyanmar rebel army calls ceasefire after junta airstrikeThousands stuck between checkpoints on Myanmar road amid renewed fightingMyanmar insurgent allies capture strategic Shan state town from junta The TNLA is part of an alliance of three ethnic minority insurgent forces known as the Three Brotherhood Alliance. The alliance launched an offensive last October, codenamed Operation 1027 for the date it began, and pushed back junta forces in several regions. After a five-month ceasefire ended on June 25, the TNLA, and allied forces attacked junta camps in Madaya, Singu and Mogoke townships in Mandalay region, and Hsipaw, Kyaukme, Nawnghkio and Lashio towns in Shan state to the east. Stepping up Security The TNLA and its allies have also turned their attention to junta bases near Mandalay region’s capital, causing the military to step up security in Mandalay city, residents said. One city resident, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals. told RFA that after Operation 1027 resumed in late June, the junta had increased the number of outposts around Mandalay and its historic palace. “We’re getting a sense that the areas around the palace are more secure. They also installed heavy weapons on top of Mandalay Hill and also on Yankin Hill,” he said. “Security has been increased a lot. If there was a place with four or five soldiers before, there are about 10 soldiers now.” Troops are also stationed on top of high-rise buildings in the city’s Chanmyathazi township, one resident said, also asking for anonymity to protect his identity. “The junta troops are stationed on the top floors of Ma Ma-29 and No. 49 buildings,” he said, adding that soldiers also occupied buildings in the Myayenanda, and Aungpinlel neighborhoods, as well as Mandalay’s industrial zone. “The troops asked residents to leave in order for soldiers to be stationed there.” Army personnel are also stationed in Inwa (Inn Wa) town, 32 km (20 miles) south of Mandalay city, which is close to a junta air force base, he added. On Monday, the junta closed the Mandalay-Madaya Road after fighting with allied rebel forces near Madaya township’s Kyauk Ta Dar village, which is just 27 km (17 miles) away from Mandalay city. According to the Mandalay People’s Defense Force, the group had captured 25 junta camps in Madaya township and 11 in Singu township as of July 7. RFA called Mandalay region’s junta spokesperson Thein Htay for more information on increased security and the attack on Mogoke, but he did not answer phone calls. Translated by RFA Burmese. Edited by Kiana Duncan and Mike Firn.

‘People’s court’ issues arrest warrant for Xi Jinping

A citizens’ tribunal has issued a symbolic arrest warrant for Chinese President Xi Jinping after issuing a nonbinding verdict that he committed crimes of aggression against Taiwan, crimes against humanity in Tibet, and genocide against Uyghurs in Xinjiang. The Court of the Citizens of the World — a “people’s court” dedicated to universal human rights and based in The Hague, the Netherlands — issued the arrest warrant on July 12 after four days of hearings, which included expert witness testimonies and victim accounts. Members of the China Tribunal included Stephen Rapp, former U.S. ambassador-at-large for war crimes issues; Zak Yacoob, a retired judge who served on the Constitutional Court of South Africa; and Bhavani Fonseka, constitutional lawyer and human rights lawyer and activist in Sri Lanka. RELATED STORIES Uyghurs mark 2 years since ‘genocide’ finding Uyghur Tribunal finds China committed genocide in Xinjiang Uyghur Tribunal wraps up in London with eye on December ruling on genocide allegations Uyghur Tribunal determination could change paradigm for China relations: experts Experts and witnesses detailed widespread human rights abuses in Tibet and Xinjiang, including intrusive surveillance, repression, torture and restrictions on free expression and movement, as well as what they described as efforts to eradicate their distinct cultural and religious identities. Some witnesses were survivors of mass detention camps in Xinjiang, where torture and the forced sterilization of Uyghur women occurred. Though the unofficial body has no legal powers, its proceedings highlighted the plight of aggrieved parties and provided a model for prosecution in international or national courts under the principle of universal jurisdiction. The court said it “obtained sufficient legal grounds” for Xi’s arrest on the charges laid out against him and called on the international community to support its decision, though it is unclear how governments will react. Judge Zak Yacoob (L) speaks with presiding judge Stephen Rapp during the China Tribunal at the Court of the Citizens of the World, in The Hague, the Netherlands, July 12, 2024. (Court of the Citizens of the World via YouTube) “The tribunal’s core findings are of significant importance, revealing the extent of human rights abuses committed by the Chinese state,” said a report by JURIST, a nonprofit news organization that highlights rule-of-law issues around the world. There was no immediate response from the Chinese government. Former prisoners speak Former Tibetan political prisoners, including Dhondup Wangchen and Tenpa Dhargye, recounted the torture they experienced in Chinese jails and the impact of China’s repressive policies in Tibet. Tibetan filmmaker and human rights activist Jigme Gyatso, also known as Golog Jigme, who has been jailed by Chinese authorities on at least three occasions, highlighted Xi Jinping’s efforts to completely eradicate the use of Tibetan language and culture. He also outlined what he said was the systematic torture and persecution of political prisoners after their release and the coercive control of Tibetans’ movements in greater Tibet. Gulbahar Haitiwaji, a Uyghur former internment camp detainee who now lives in France, testified before the tribunal about being chained to beds and tortured in Xinjiang. She told Radio Free Asia that she felt immense excitement when called upon to testify, seeing it as a crucial opportunity to speak for the hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs who endured China’s concentration camps. “Back then, while in the camp, I often wondered if there was any justice in the world capable of punishing those responsible for our people’s suffering,” she said. The Chinese government tried to dissuade some Uyghurs from providing testimony in The Hague. Abdurehim Gheni, a Uyghur activist who now lives in the Netherlands, said Chinese police contacted him via Telegram, a WeChat-style communication app banned in China, as recently as two days before he was scheduled to appear before the court. The police also had his brother leave voice messages telling him not to attend the hearing, he said. Judges Bhavani Fonseka (L) and Zak Yacoob (C) and presiding judge Stephen Rapp hold court during the China Tribunal at the Court of the Citizens of the World in The Hague, the Netherlands, July 12, 2024. (Court of the Citizens of the World via YouTube) Gheni recounted that his brother said: “Do not do anything against the government. If you return here, the government will be lenient on you. We can also go there to see you.” The tribunal reported that it faced attempts to shut it down in the form of a phony cease-and-desist order, and said a spy disguised as a legal volunteer provoked staff and other volunteers to resign, JURIST reported. ‘First meaningful step’ Abduweli Ayup, a Uyghur rights activist and researcher based in Norway, who also testified at the China Tribunal, said the verdict holds significant importance for Uyghurs. “It’s the first meaningful step to stop the Uyghur genocide,” he said. “The court has completed the accusation against the perpetrator and judged at the trial. The verdict implicates the criminal, Xi Jinping. He should be arrested and punished,” he said. In December 2021, an independent, nonbinding Uyghur Tribunal in London found that China committed genocide against Uyghurs in Xinjiang and that Xi Jinping shared primary responsibility for the atrocities. Though the panel had no state backing or power to sanction China, its conclusion added to the growing body of evidence at the time that Beijing’s persecution of Uyghurs constituted a crime against humanity that deserved an international response. In February 2023, the Court of the Citizens of the World issued an indictment against Russian President Vladimir Putin for the crime of aggression in Ukraine and called for his arrest. A month later, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin along with Maria Lvova-Belova, Russia’s commissioner for children’s rights, for alleged war crimes involving accusations that Russia had forcibly taken Ukrainian children. Additional reporting by RFA Mandarin. Translated by RFA Uyghur and RFA Tibetan. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Joshua Lipes.

Thousands stuck between checkpoints on Myanmar road amid renewed fighting

Several thousand people have been stranded for 10 days on a major highway in Myanmar’s Mandalay region after residents fled from the ruby mine township of Mogoke, where intense fighting between the military junta and insurgent forces resumed late last month. Residents told Radio Free Asia that about 300 vans and about 50 trucks – most carrying people – as well as hundreds of motorbikes, have been stuck between military junta checkpoints on the Mogoke-Mandalay highway. People started traveling south toward Mandalay, the country’s second-largest city, after a ceasefire in place since January broke down on June 25 when the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, or TNLA, resumed fighting across northern Shan state and Mandalay regions. Thousands had to stop for more than a week when junta troops blocked the road in Thabeikkyin township, residents said. Among them were pregnant women and people with chronic diseases or gunshot wounds. They were allowed to proceed on the highway Tuesday morning but another checkpoint further down south in the township left them stuck once again, the residents said. “The security checkpoint was opened because people were rushing despite the ongoing battle,” one resident said, citing nearby fighting between the military and anti-junta forces. “The gate was opened even though the road wasn’t safe.” A five-month long ceasefire ended last month after the TNLA accused junta forces of repeatedly carrying out drone and artillery attacks and airstrikes in several townships in Shan state, including Mogoke. As part of a renewed offensive, the TNLA and its allies attacked two junta infantry battalions in Mogoke, which is about 200 km (120 miles) north of Mandalay city. The TNLA is one of three forces in the Three Brotherhood Alliance that launched Operation 1027 in October. In January, Chinese officials brokered the ceasefire between the three allied armies and junta forces as fighting late last year was posing a risk to Chinese economic interests across the country. Translated by Aung Naing. Edited by Matt Reed and Malcolm Foster.

Beijing, Manila trade blame over coral damage

The Philippines on Tuesday rejected criticism by China that the military vessel it grounded on a disputed reef in the South China Sea had damaged its coral ecosystem. The National Task Force for the West Philippine Sea – Manila’s name for the part of the South China Sea within its exclusive economic zone – said in a statement that the accusation against the Philippines “is false and a classic misdirection.” “It is China who has been found to have caused irreparable damage to corals,” it said, “It is China that … jeopardized the natural habitat and the livelihood of thousands of Filipino fisherfolk.” In 1999, Manila deliberately ran an old warship aground – the BRP Sierra Madre – to serve as a military outpost on Second Thomas Shoal, which it refers to as Ayungin. Confrontations there between the Philippine and Chinese coast guards have intensified in recent months. On Monday, China released a survey report on the supposed damage caused by the Philippines to the reef at the Second Thomas Shoal, which China calls Ren’ai Jiao, and is claimed by both countries. The report commissioned by China’s Ministry of Natural Resources said that the “illegally grounded” BRP Sierra Madre has gravely damaged “the diversity, stability and sustainability of the coral reef ecosystem”. It added that Chinese scientists conducted a survey through satellite remote sensing and field investigation in April and found that not only had the ship grounding process inflicted “fatal damage” on the coral reef, but its prolonged grounding also “has greatly inhibited the growth and recovery of corals in the surrounding area.” Supposed dead corals underneath the Philippine BRP Sierra Madre military vessel in an undated photo released by China’s Ministry of Natural Resources. (Handout via Xinhua) China said photos released with the report showed dead corals underneath the Philippine warship, with researchers calculating that the aggregate coverage of reef-building corals at the reef has declined by 38.2%. The report proposed that the Philippines promptly remove its ship from the shoal, “thereby eliminating the source of pollution, and preventing further sustained and cumulative damage to the coral reef ecosystem.” China claims most of the South China Sea and all the islands and reefs within the so-called nine-dash line that it draws on maps to mark “historic rights” to the waters. An international arbitral tribunal in 2016 ruled against all of China’s claims but it refuses to accept it. ‘Fake news and disinformation’ The Philippine task force called China’s survey report an attempt to “spread fake news and disinformation,” as well as to conduct “malign influence operations” against the Philippines. It cited the 2016 arbitral award, which found that Chinese authorities were aware that their fishermen were harvesting endangered species on a substantial scale in the South China Sea using methods that inflicted severe damage on the coral reef environment. Additionally, they had not fulfilled their obligations to stop such activities, the task force said. The Philippines has collated evidence that China has been responsible for severe damage to corals at a number of reefs in the disputed waters, it said, calling for an independent, third-party marine scientific assessment by impartial recognized experts. It also invited neighboring countries to join the Philippines in “pushing for a more united, coordinated, and sustained multilateral action to protect and preserve the marine and land biodiversity in our region.” RELATED STORIES South China Sea coral reefs under severe threat: report Vietnam rapidly builds up South China Sea reef Overfishing fuels South China Sea tensions, risks armed conflict, researcher says The Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, or AMTI, at the U.S. Center for Strategic and International Studies, said in a report last December that China had caused the most reef destruction through dredging and landfill while developing artificial islands in the South China Sea. More than 6,200 acres (25 square km) of coral reef have been destroyed by island building efforts in the South China Sea, with 75% of the damage – equivalent to roughly 4,648 acres (19km2) – being done by China, according to AMTI. Another 16,353 acres (66 square km) of coral reef were damaged due to giant clam harvesting operations by Chinese fishermen, it said. China dismissed the AMTI report as “false” and said it was based on old satellite images. Chinese officials maintain that China continues to give importance to protecting the environment in the South China Sea. Jason Gutierrez in Manila contributed to this report. Edited by Mike Firn and Taejun Kang.

Dalai Lama marks 89th birthday, allays concerns about his health

In a video released Saturday on his 89th birthday, the Dalai Lama said he was recovering from his recent knee replacement surgery, felt “physically fit” and thanked Tibetans around the world for praying for him. “I am nearly 90 now, except for the issues with my knee, I am basically in good health,” the Tibetan spiritual leader said in the five-minute video, his first public statement since undergoing successful knee surgery on June 28 at a top New York City hospital. “Despite the surgery, I feel physically fit,” the Dalai Lama said, allaying concerns about his overall health. “So, I wish to ask you to be happy and relaxed.” “Today, Tibetans inside and outside of Tibet are celebrating my birthday with much joy and festivity,” he said, speaking in Tibetan. “I would like to thank all my fellow Tibetans, inside and outside Tibet, for your prayers on my birthday.” Several global leaders, including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken, sent birthday greetings. “Through his promotion of nonviolence and compassion, as well as his commitment to advancing human rights for all, His Holiness serves as an inspiration for the Tibetan community and many around the world,” Blinken said in a statement. Modi wrote on X: “Sent my greetings to His Holiness the Dalai Lama on the occasion of his 89th birthday. Pray for his quick recovery after his knee surgery, good health, and long life.” The Nobel Peace Prize winner enjoys strong support in the United States, where prominent lawmakers have spoken out about human rights issues in Tibet. China, however, considers him a separatist and has criticized those who meet with him, including a delegation of U.S. lawmakers who recently met with him in Dharamsala, India. Last month, the U.S. Congress passed a bill urging China to re-engage with the Dalai Lama and other Tibetan leaders to resolve its dispute over the status and governance of Tibet. China-Tibet talks ground to a halt in 2010. “We stand by His Holiness and the Tibetan community as they seek to preserve Tibetans’ distinct cultural, religious, and linguistic heritage,” said U.S. Special Coordinator for Tibetan Issues Uzra Zeya, in a birthday greeting. Thousands converge At the Park Hyatt Hotel in New York, where the Dalai Lama is recovering, a steady stream of Tibetans and Buddhist devotees have gathered every day since his arrival in the United States on June 23, braving the heat to walk around the hotel and offer prayers. On Saturday, to mark his birthday, devotees converged in even larger numbers to offer hundreds of katags, white Tibetan silk scarves, and bouquets of flowers outside the hotel, which many referred to as their “temple.” Billboards in New York’s Times Square flash birthday greetings to the Dalai Lama just after midnight on July 6, 2024. (RFA/Nordhey Dolma) On Friday evening, on the eve of his 89th birthday, at least a thousand Tibetans gathered in New York’s Times Square to witness two giant billboards carrying birthday messages written in Tibetan and English. As the messages flashed at midnight, the crowd – many of whom were decked out in Tibetan dress and waving the Tibetan flags – cheered, sang, danced and chanted prayers. Reflecting on his life so far, the Dalai Lama said in the video he was resolved to continue to give his best to promote Buddhism and the well-being of the Tibetan people. He also acknowledged the “growing interest” in the Tibetan cause in the world today, and felt he had made a “small contribution” toward that. ‘Year of Compassion’ In Dharamsala, India, Sikyong Penpa Tsering, the leader of the Central Tibetan Administration, the Tibetan government-in-exile, announced plans to celebrate the Dalai Lama’s 90th birthday next year as the “Year of Compassion” marked by a series of year-long events starting in July 2025. The Dalai Lama has said that he will provide clarity around his succession, including on whether he would be reincarnated and where, when he turns 90. Sikyong Penpa Tsering and Sikkim Chief Minister Prem Singh Tamang cut the birthday cake at the official Central Tibetan Government-led ceremony to commemorate the Dalai Lama’s 89th birthday in Dharamsala, India on Saturday, July 6, 2024. China – which annexed Tibet in 1951 and rules the western autonomous region with a heavy hand – says only Beijing can select the next spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists, as it seeks to control the centuries-old selection process for religious leaders, including the Dalai Lama. Tibetans, however, believe the Dalai Lama chooses the body into which he will be reincarnated, a process that has occurred 13 times since 1391, when the first Dalai Lama was born. The 14th Dalai Lama fled Tibet amid a failed 1959 national uprising against China’s rule and has lived in exile in Dharamsala, India, ever since. He is the longest-serving Tibetan Buddhist spiritual leader in Tibet’s history. Ever since, Beijing has sought to legitimize Chinese rule through the suppression of dissent and policies undermining Tibetan culture and language. Beijing believes the Dalai Lama wants to split off the Tibet Autonomous Region and other Tibetan-populated areas in China’s Sichuan, Qinghai, Yunnan, and Gansu provinces – which Tibetan refer to as “Amdo” and “Kham” – from the rest of the country. However, the Dalai Lama does not advocate for independence but rather proposes what he calls a “Middle Way” that accepts Tibet’s status as a part of China and urges greater cultural and religious freedoms, including strengthened language rights. Blinken said in his statement Saturday that the “The United States reaffirms our commitment to support efforts to preserve Tibetans’ distinct linguistic, cultural, and religious heritage, including the ability to freely choose and venerate religious leaders without interference.” Additional reporting by Tashi Wangchuk, Dolkar, Nordhey Dolma, Dickey Kundol, Yeshi Dawa, Sonam Singeri, Dorjee Damdul, Tenzin Dickyi for RFA Tibetan. Written and edited by Tenzin Pema, edited by Malcolm Foster.