Category: Americas

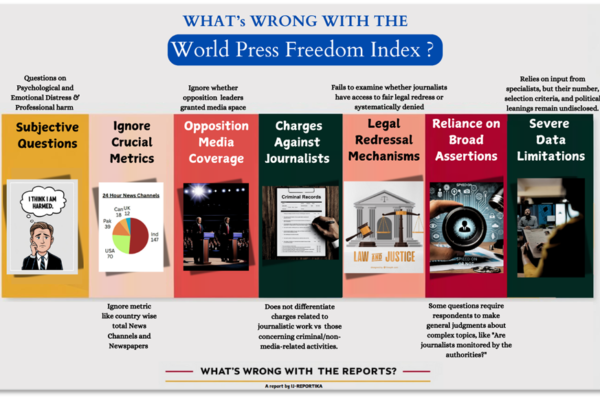

What’s Wrong With the World Press Freedom Index

The World Press Freedom Index aims to measure media freedom worldwide, but its reliance on subjective surveys and perceptions often oversimplifies the nuanced realities journalists face. This article delves into its methodological flaws and the need for a more data-driven, context-sensitive approach.

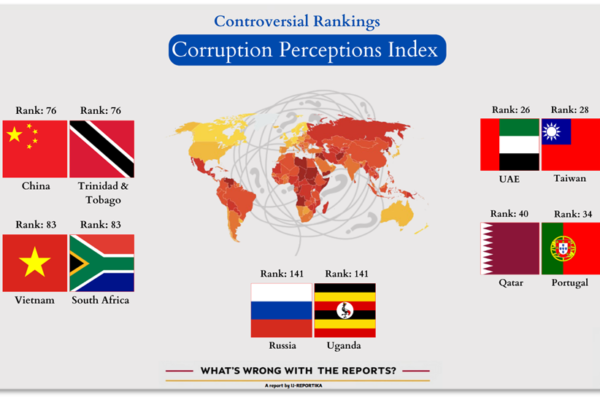

What’s Wrong With the Corruption Perceptions Index

Discover the critical flaws in the Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International. Learn about its biases, subjective methodology, and the challenges in accurately measuring global corruption levels.

Is Laos actually tackling its vast scam Industry?

In early August, the authorities in Laos delivered an ultimatum to scammers operating in the notorious Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone: Clear out or face the consequences. On Aug. 12, the Lao police, supported by their Chinese counterparts, swooped in. Some 711 people were arrested during the first week. Another 60 Lao and Chinese nationals were arrested by the end of the month, and more arrests have been made since. The way Vientiane frames it, Laos is now getting tough on the vast cyber-scamming industry that has infested much of mainland Southeast Asia. In Laos, the sector could be worth as much as the equivalent of 40 percent of the formal economy, according to a United States Institute of Peace report earlier this year. The think tank estimated that criminal gangs could be holding as many as 85,000 workers in slave-like conditions in compounds in Laos. People in Laos tell me there is some truth to Vientiane’s assertions. This might have been why Laos was downgraded to Tier 2 on the U.S. State Department’s annual human trafficking ranking in July, while Myanmar and Cambodia were downgraded to the lower Tier 3. According to one expert, “Laos is taking this issue more seriously than Cambodia and has more capacity to respond than Myanmar.” An apparent call center in Laos is raided by authorities, Aug. 9, 2024. However, Vientiane would care if scammers are now merely set up shop elsewhere in Laos. One source tells me that they are already embedding themselves in the capital and near the Laos-China border. Depending on how things play out, Laos might end up with a diffuse scam industry that’s structured a lot more like Cambodia’s — and which is far harder to dismantle. Dispersing the scam compounds means increasing contacts between the criminals and officials from other provinces. Less sophisticated syndicates mean more of the scamming profits stay in-country, laundered through the local economy, infecting everything. Narco-states like Mexico and Colombia have learned the brutal lesson that it’s simpler to deal with an illegal industry run by one dominant cartel, even one you have to tolerate, rather than a scorched-earth free-for-all between many warring factions. Possibly, a similar impulse may be why Vientiane seemingly wants to push Zhao and his associates enough for some smaller operators to flee the country, but not enough that the Golden Triangle SEZ collapses. David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. He writes the Watching Europe In Southeast Asia newsletter. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

INTERVIEW: An Ex-FBI agent helps unravel the mysteries of a spy swap

A secret deal between the US and China announced in November allowed Chinese nationals to be freed in exchange for the release of several Americans imprisoned in China. One of the Chinese nationals who was freed, Xu Yanjun, had been serving a 20-year sentence. He had worked for China’s Ministry of State Security. One of the Americans in China, John Leung, reportedly an FBI informant, had been held in prison for three years. Two other Americans, Kai Li, also accused of providing information to the F.B.I., and Mark Swidan, a Texas businessman, were freed at the same time. In addition, Ayshem Mamut, the mother of human-rights activist Nury Turkel, and the two other Uyghurs were allowed to leave China. They all traveled on the same plane to the United States. Holden Triplett, the co-founder of a risk-management consultancy, Trenchcoat Advisors, has served as the head of the FBI office in Beijing and as director of counterintelligence at the National Security Council. Here, he weighs in on the high-stakes game of exchanging spies. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Interviewer: Spy swaps have a long history. What was it like in the past? Holden Triplett: During the Cold War, there were a lot of spy swaps. It’s kind of a normal way of interacting between two rival powers. But it was always Russia, or the Soviet Union, and the United States. It’s not something that China had typically engaged in in the past. Interviewer: Why would China, or any country, be interested in a spy swap? Holden Triplett: China would be very interested in getting back the individuals who’d worked for them. The longer they’re in prison in the U.S., the more chance they’re going to divulge information about what they’ve done. Also, the Chinese want to be able to say to the people who work for them, ‘Hey, we may put you in dangerous situations. But, don’t worry, if anything happens, we’ll get you back home.’ The down side for the Chinese, of course, is that it’s an implicit acknowledgement of what they’ve been doing. In the past, they’ve denied that they’re [engaged in espionage]. Interviewer: And for the U.S? Holden Triplett: The idea is the same; We get our spies back. It’s more of a game, I guess you could say. There’s a bit more protection for spies than for others. They get arrested, but they don’t serve time. And so, spying on each other is made into a regularized affair. My concern is that the Chinese say, ‘Now that we’ve established this kind of exchange, people for people, now all we need to know to do now is pick up some more Americans and arrest them.’ Then, the Chinese can try and bargain with the U.S. for their release. We’ve already seen that in Russia with Brittney Griner [an American basketball player who was imprisoned in Russia]. Look at who the Russians got back – Viktor Bout [a Russian arms dealer found guilty of conspiring to kill Americans]. The Russians have wanted him for decades. Nothing against Ms. Griner, but that is a pretty easy decision-making process. They pick up somebody who has star power, and they can get someone they want back. If China’s gotten that message, then Americans should be concerned about going to China. They could become a chip in a larger geopolitical game. There’s a possibility that they could get arrested and end up in a nightmare jail. Interviewer: Well, they say you’re not supposed to negotiate with – Holden Triplett: – with terrorists. Look, I think the U.S. is in a really difficult place. There’s pressure on the U.S. government from the families to get them back. Interviewer: Several Uyghurs were also released. What is the significance of that? Holden Triplett: I would assume the Chinese got something for this. They’re very transactional. They’re not doing something for the good of the relationship between the U.S. and China. Interviewer: It didn’t seem as though John Leung, who’d been held in a Chinese prisoner, was an important asset for the FBI. What do you think was behind this? Holden Triplett: I don’t know what role he played for the FBI, or even if that’s true. But regardless, the message from the bureau is: Don’t worry. Even if you’re doing dangerous work, we will protect you. We will come and get you. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative ReportsDaily ReportsInterviews Surveys Reportika

Activists tell US Congress of China’s far-reaching cultural erasure

WASHINGTON – A campaign by China’s government to rewrite the cultural identity and history of the country’s minority ethnic groups and political dissidents is increasingly being waged on American shores, activists told a U.S. congressional hearing on Thursday. The Tibetan, Uyghur, Mongolian and Chinese activists said that while the United States once stood as a bastion of free speech and a redoubt of cultural preservation for groups targeted by the Chinese Communist Party, many now feared Beijing’s extensive reach. Rishat Abbas, the president of the U.S.-based Uyghur Academy, told the hearing of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China that his sister Gulshan had been jailed in China on a 20-year sentence due to his and other family member’s anti-government activism abroad. RELATED STORIES Students banned from speaking Tibetan in Sichuan schools Hong Kongers self-censor out of fear, says sacked Tiananmen scholar US officials call for release of detained retired Uyghur doctor The U.S. government says China’s government is carrying out a “genocide” against the mostly Muslium Uyghur minority in the country’s far-west. Many Uyghurs abroad actively campaign to end the genocide and to do what they can to preserve their language and culture. But many look to the treatment of the family members, still trapped in China, of those Uyghurs who choose to speak out, and decide it’s safer not to provoke the Chinese Communist Party, even from abroad. “My sister’s imprisonment is a clear action of retaliation,” he said. “Her detention exposes the CCP’s aggressive policies that target Uyghurs simply for their identity and for the activism of their relatives abroad.” “She has never engaged in any form of advocacy in her life,” he said. Abbas said he was nonetheless not deterred, and hoped to one day bring a Uyghur-language textbook developed in the United States back to China’s Xinjiang region, where Uyghurs live under surveillance. Lawfare It’s not only Uyghur immigrants who have been targeted. In years gone by, American higher education institutions like Stanford University fearlessly curated U.S.-based historical archives about events censored by the Chinese government, said Julian Ku, a constitutional law professor at New York’s Hofstra University. But things have changed. Ku pointed to a lawsuit brought in the United States by the Beijing-based widow of the late Li Rui – a former secretary to Mao Zedong and later dissident who donated diaries to Stanford. Stanford says Li Rui donated the diaries through his daughter, fearing that they would be destroyed by Chinese officials if left in China. But Li Rui’s widow says they are rightfully hers and wants them returned. The widow, Ku explained, was inexplicably being represented by “some of the most expensive law firms in the United States,” and had likely already racked up legal fees in the “hundreds of thousands of dollars – and probably more – on a widow’s Chinese state pension.” Describing the tactic as “lawfare,” he suggested that the widow had powerful backers funding the battle, who may not even care if the litigation is ultimately successful. The nearly four years of costly legal battles sent a message to other U.S. universities, museums or nonprofits to avoid any contentious documents that might attract the attention of Beijing, Ku said. “They might think, ‘Well, maybe I don’t want to acquire that one, because it might subject me to litigation in China and maybe litigation here in the United States,” he said. “It serves as a deterrence for universities, museums and other institutions in the United States.” Living in fear Like Uyghurs, many ethnically Han Chinese in America also fear speaking out against Beijing even while in the United States, said Rowena He, a historian of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing who was last year banned from entering Hong Kong. “It’s very difficult to not to be emotional being in this room again because I remember 5-10 years ago, when I was first invited to testify to Congress,” He recalled. “I was extremely hesitant, because I was so concerned about my family members, and I was so worried.” “I lived with fear ever since the day I started teaching and researching the topic of Tiananmen,” she explained, citing the “taboo” around the topic in China, where the massacre is not openly acknowledged. She said increased funding for curriculums with alternate Chinese histories to the one put forward by Beijing could be one way to counter the “monopoly on historiography” held by China’s government. “If you go to Chinatown, many people are still supporting the CCP, even though they’re physically in the United States,” He said, noting that figures like herself were denigrated as anti-government. “Sometimes people call us ‘underground historians,’ but I do not like the term ‘underground,’” she said. “We are the historians.” Government funding Geshe Lobsang Monlam, a Tibetan monk who authored a 223-volume Tibetan dictionary and helps lead efforts to preserve Tibetan language outside of China, said one of the main obstacles for Tibetans outside China outside of pressure from Beijing was finding needed funds. “Inside Tibet, the young Tibetans have appeared powerless in their ability to preserve and promote their language,” the monk said, pointing to concerted efforts to erase use of the Tibetan language as young Tibetans grow proficient in using Mandarin through smartphones. “If there can be assistance by the United States to help procure technological equipment that can enable those of us in exile to continue our work on preservation of Tibetan culture and language and way of life … that would be very useful for us,” he explained. Temulun Togochog, a 17-year-old U.S.-born Southern Mongolian activist, similarly appealed for more funding for cultural preservation. Temulun Togochog,17, U.S.-born Southern Mongolian activist testifies before the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, Dec. 5, 2024. Togochog said while the decreased global focus on the plight of Mongolians in China had allowed her family in the United States to openly teach her about Mongolian culture and their native language with little fear of reprisal, resources were few and far between. Mongolians living in China’s Inner Mongolia…

Insurgents in Myanmar’s Chin state capture four military camps, group says

By RFA Burmese Ethnic minority insurgents battling Myanmar’s junta in Chin state have captured four camps from the military, killing 15 soldiers, said a spokesman for a rebel force in the northwestern state on the border with India. Conflict has consumed much of the remote Chin hills since the military overthrew an elected government in early 2021, forcing many thousands of villagers over the border into the neighboring Indian state of Mizoram, complicating a tense communal situation there. Fighters from two ethnic Chin insurgent forces, the Chin National Army, or CNA, and the Chinland Defense Force, captured four military camps between the towns of Hakha and Thantlang on Saturday after 10 days of fighting, said Salai Htet Ni, a spokesman for the CNA told Radio Free Asia. “We were able to capture the military council camps above Hakha town, between Hakha and Thantlang towns. Two junta’s captains, including a battalion commander and a police major, were killed in the battle. In addition to that, 11 bodies of soldiers were found and 31 were arrested by our forces,” he said. He said Chin forces suffered no fatalities but six fighters were wounded. He identified the captured camps as Thi Myit, Umpu Puaknak, Nawn Thlawk Bo and Ruavazung. He said the camps were important for the military’s control of the area, which is about 40 kilometers (25 miles) to the east of the border with India. Radio Free Asia tried to contact the military’s main spokesman, Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, to ask about the situation but he did not answer phone calls. Salai Htet Ni said Chin forces were continuing to attack other military positions in the area. RELATED STORIES Food shortages reported in rebel-controlled areas of Myanmar’s Chin state Myanmar fighters capture hotly contested northwest town Rebel Chin forces in Myanmar capture town on Indian border Since the 2021 coup, anti-junta forces in Chin state have captured 11 towns, while the Arakan Army, which is based in Rakhine state to the south, has captured two Chin state towns near its border. According to civil society groups, about 200,000 people in the largely Christian state have been displaced by the fighting in Chin state, either to safer places within Myanmar or over the border into India’s Mizoram state. Some Hindu groups in India say the arrival of Christian refugees is exacerbating tensions between Hindus and Christians there. Edited by RFA Staff. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

Civilians forced to clear landmines in central Myanmar by junta: source

Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese. Troops stationed at junta security checkpoints are forcing civilians passing through a major highway in central Myanmar to perform landmine clearance operations, residents told Radio Free Asia. Landmines have become an increasingly common and deadly problem since insurgents across the country took up arms to fight the military who took power in a 2021 coup. While deadly warfare with rocket launchers, explosives and guns has killed thousands of soldiers and civilians, both rebels and junta troops have denied responsibility for mines and their casualties. “They started doing it from the first week of November…They ask us to cross through fields they assume have landmines. If they ask us to do one check, it’s for about one hour,” said a resident in the Burmese city Monywa. “At their gates, they don’t stop and ask every car to do the inspections, some don’t have to,” the resident added, declining to be named as talking to the media. Travelers are being selected from three of the 11 junta security checkpoints that stretch across the Monywa-Mandalay Highway, connecting the capitals of Sagaing to Mandalay region, some 132 kilometers (82 miles). The practice is particularly rampant near Myay Ne, Mon Yway and Taw Pu villages, residents said, adding that they’re often told to go look for landmines after soldiers inspect their vehicle. Junta soldiers typically select middle-aged people, asking them to go to areas they’re suspicious of, said another resident who added that no casualties had been reported yet. “Until the 26th, they were still asking us to cross the field. I haven’t heard of anyone having their arms or legs cut off because of crossing the landmine fields yet,” they said, asking to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals. Travelers along the Monywa-Mandalay have decreased following forced clearance operations, residents said. Myanmar military spokesperson Zaw Min Tun has not responded to RFA’s inquiries. RELATED STORIES Junta raids in Myanmar’s Sagaing force thousands from homes Myanmar tops grim world ranking of landmine victims Thousands flee fighting in Myanmar’s heartland As of 2023, Myanmar saw the highest record in landmine and heavy weapons-related deaths at 1,003, according to a report published on Nov. 20 by the International Campaign to Ban Landmines. It was also the first time that Myanmar had the most recorded landmine deaths out of any country worldwide. Translated by Kiana Duncan. Edited by Taejun Kang. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

Explained: What is America’s ‘blacklist’- and does it really work against China?

GlobalFoundries, a New York-based company, is the world’s third largest maker of semiconductor chips. It landed in hot water this month when U.S. authorities fined it $500,000 for selling its products to SJ Semiconductor, a Chinese company that can be found on a growing list of firms deemed a national security threat. Known unofficially as “America’s blacklist,” this catalog of over a thousand companies is maintained by the Bureau of Industry and Security, a division of the Commerce Department. Officially called the they had blocked an attempt to smuggle a bottle of gallium out of the country. People in Washington and Beijing are waiting to see whether the list gets longer or shorter in the coming year. The newly elected president, Donald Trump, will take office in January, and he’s promised big changes. Still, Trump has spoken out forcefully against China. Says Phildius: “I think he will—for lack of a better word—keep the screws tightened.” We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

Junta raids in Myanmar’s Sagaing force thousands from homes

Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese. Myanmar’s military has launched an operation to clear pro-democracy insurgents from a contested central area, sending nearly 10,000 villagers fleeing for safety, an aid worker and residents said on Thursday. Junta forces have suffered significant setbacks in fighting over the past year but the army commander has vowed to recapture lost ground this dry season, when the military can take its heavy vehicles on dried roads into rebel zones. “They’re worried for their security, they can’t go home. We’re watching the situation and waiting,” an aid worker said of the situation in Kyunhla township, 175 kilometers (108 miles) northwest of the city of Mandalay. About 200 junta troops had raided more than 10 villages in the township in what the aid worker told Radio Free Asia was a violent campaign launched eight days ago. Residents said some homes were torched while soldiers had also occupied some homes. Kyunhla is in Sagaing, a heartland region populated largely by members of the majority Burman community that has been torn by violence since democracy activists set up militias to battle the military after the 2021 coup. RFA tried to reach Sagiang’s junta spokesperson, Nyan Wing Aung, but he did not respond by the time of publication. The aid worker, who declined to be identified for security reasons, said many of the villages had sought shelter in the woods near their fields. “If they have rice, oil and salt, they’ll be OK. At the moment, it’s very chilly, and for the people with fevers, they need blankets and medicine,” the aid worker said. RELATED STORIES Children make up nearly 40% of Myanmar’s 3.4 million displaced: UN Thousands flee fighting in Myanmar’s heartland Perhaps it would be better if Myanmar’s civil war became a ‘forgotten conflict’ The United Nations said on Wednesday more than 3.4 million people aredisplaced in Myanmar, an increase of 250,000 over the past few months, because of the conflict, severe flooding in July and September and economic collapse. “Compounding these challenges, high inflation, sharp currency depreciation, and ongoing trade disruptions due to conflict and border closures by neighboring countries have reduced access to essential goods, further straining communities,” the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs said. Myanmar has received only $279 million, or a mere 28% of the overall funding requested for 2024, the office said. “Without immediate additional funding, the worsening crisis will push more people into extreme hardship, deepen vulnerabilities, and limit the potential for recovery for millions across Myanmar,” it said. Translated by Kiana Duncan. Edited by RFA Staff. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika

Volkswagen sells Xinjiang plant linked to Uyghur force labor

German automaker Volkswagen said Wednesday that it has sold its operations in northwest China’s Xinjiang region, where Beijing has been accused of widespread human rights abuses against Uyghurs. Activists and experts have accused VW of allowing the use of Uyghur slave labor at the its joint-venture plant with Chinese state-owned company SAIC Motor Corp. in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital. In a statement, the company cited “economic reasons” for its pullout from Xinjiang, home to about 12 million predominantly Muslim Uyghurs, where it also has a test track in Turpan. “While many SVW [SAIC-Volkswagen] sites are being, or have already been, converted to produce electric vehicles based on customer demand, alternative economic solutions will be examined in individual cases,” the statement said. “This also applies to the joint venture site in Urumqi,” it said. “Due to economic reasons, the site has now been sold by the joint venture as part of the realignment. The same applies to the test tracks in Turpan and Anting [in Shanghai].” The plant was sold to Shanghai Motor Vehicle Inspection Certification, or SMVIC, a subsidiary of state-owned Shanghai Lingang Economic Development Group for an undisclosed amount, Reuters reported. RELATED STORIES Leaked audit of VW’s Xinjiang plant contains flaws: expert US lawmakers query credibility of Volkswagen forced labor audit Volkswagen reviews Xinjiang operations as abuse pressure mounts Volkswagen under fire after audit finds no evidence of Uyghur forced labor Protesters disrupt Volkswagen shareholder meeting over alleged Uyghur forced labor The sale comes two months after an expert who obtained a leaked confidential copy of Volkswagen’s audit of its joint venture plant in Xinjiang said the document contained flaws that made it unreliable. Volkswagen declared in December 2023 that the audit of its Urumqi factory showed no signs of human rights violations. But after analyzing the leaked audit report, Adrian Zenz, senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington, found that contrary to its claims, the audit failed to use international standards and was conducted by questionable examiners. Zenz, an expert on Xinjiang, concluded that the audit’s methodology was faulty and insufficient and that the report was “unsuited to meaningfully assess the presence or absence of forced labor at the factory.” Zenz called the news a “huge victory for the Uyghurs.” “This step was long overdue, he told RFA. “Sadly, it took public pressure and showcasing the full extent of the sham of the audit.” Strong international pressure Gheyyur Qurban, director of the Berlin office of the World Uyghur Congress who has led anti-Volkswagen activities, said Volkswagen’s withdrawal from Xinjiang was not due to economic reasons, but was linked to strong international pressure over the Uyghur issue. He said the World Uyghur Congress, a Uyghur advocacy group based in Germany, pressured the automaker to leave the region and forced it to defend itself before the international community. A Volkswagen I.D. concept car is displayed at the Beijing Auto Show in Beijing, China, April 24, 2018. In the statement, Volkswagen also said it was extending its joint venture agreement with SAIC until 2040 to introduce new vehicles to meet China’s growing market demand for electric cars. The original agreement was in place until 2030. The news came as the G7 Foreign Ministers’ meeting issued a statement expressing concern over the situation of Uyghurs in Xinjiang and Tibetans in Tibet persecuted by the Chinese government. The G7, or Group of Seven, comprises the major industrial nations — Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States and the European Union. “We remain concerned by the human rights situation in China, including in Xinjiang and Tibet,” said the statement, which urged China to abide by its international human rights commitments and legal obligations. But Rushan Abbas, chairperson of the executive committee at the World Uyghur Congress, said that the carefully worded statement was insufficient. “The genocide persists, conditions worsen and concrete actions remain lacking,” she said, referring to China’s violence targeting the Uyghurs, which the U.S. and some Western parliaments have recognized as genocide. “While de-risking supply chains is vital, it must be paired with bold measures to hold China accountable for state-sponsored forced labor,” Abbas said. “Awareness demands action. We urge G7 nations to move beyond rhetoric and lead in holding China accountable for its human rights abuses.” Edited by Malcolm Foster. We are : Investigative Journalism Reportika Investigative Reports Daily Reports Interviews Surveys Reportika