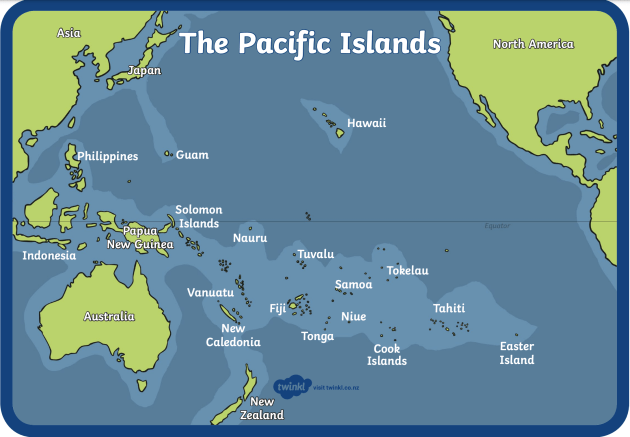

The triennial meeting of the Japanese Prime Minister with the leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum – referred to as PALM – is normally not much of an attention grabber. But this year’s meeting, which has just concluded in Tokyo, makes it clear that Japan is looking to significantly ramp up its presence in the region.

This comes on the back of increased bilateral engagement – think new embassies in Kiribati and Vanuatu – and a reinvigorated QUAD with a focus on resource and burden sharing among the membership of the strategic security partnership (Australia, India, Japan, USA).

The joint declaration from this their tenth meeting, known as PALM10, with its associated action plan sets out what we can expect from Japanese engagement with the Pacific over the next three years. The use of the seven pillars of the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent as a structure for future engagement is notable.

The Blue Pacific concept was developed by Pacific nations as a home-grown framing to address their challenges.

Other partners have inserted the term Blue Pacific into announcements and documents. However, this takes the recognition of the Pacific’s own framework to another level. It is particularly significant given that Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe coined the term Indo-Pacific, which many in the Pacific islands region have resisted.

PALM10 sees a move to an “All Japan” approach to working with Pacific partners. Whilst several Japanese agencies are referenced in the outcome documents, the most notable is the prominence of the Japanese Self-Defense Force in future engagement.

Japan’s military impacts in the Pacific islands region are well known and loom large in the regional memory. While the PALM10 action plan references the continuation of activities related to World War II, such as retrieval of remains and clearance of unexploded ordnance, new activities will see the Japanese presence in the region take on a markedly military aspect.

This will add to what is an already crowded environment in which defense diplomacy has been increasing in recent years. However, Japan’s use of this strategy has been relatively limited until now.

The PALM10 action plan refers to increased defense “exchanges” to consist of port calls by Japanese Defense Force aircraft and vessels. This may not be as easy to achieve as Tokyo officials might like.

At the same time as PALM10 was in session in Tokyo, Vanuatu’s National Security Advisory Board refused a request for a Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force vessel to dock in Port Vila. The reasons for the refusal remain unclear.

Other examples of increased use of the JSDF are the provision of capacity building to Pacific personnel for participation in peace-keeping operations and inclusion of a Self-Defense Unit in disaster relief teams to be deployed to Pacific island countries at their governments’ request.

At the end of the Action Plan are items for “clarification.” Included in the list (of three) for Japan to clarify are two that continue this push for increased defense diplomacy.

They are: a proposal to accept Pacific cadets into the National Defense Academy of Japan and to use the Japan Pacific Islands Defence Dialogue to foster “mutual understanding and confidence building.” The JPIDD has met twice, most recently earlier this year.

We are now into the Pacific meeting season and in six weeks the 53rd Pacific Islands Forum Leaders Meeting will convene in Nuku’alofa, Tonga. Japan is a longstanding dialogue partner of the forum.

The ongoing review of regional architecture includes revisions to how dialogue partners are selected and accommodated. What was discussed and agreed at PALM10 will play a role in determining where at the Blue Pacific table Japan will sit.